Why Are Some Charters Losing Title I Funds? It’s Anyone’s Guess

Tommy Reddicks has spent many of the last several weeknights cramming, furiously reading and writing into the late evening hours.

This is not your typical late-night study session. Reddicks is not a student – he’s the executive director of the Paramount School of Excellence, a K-8 charter school on the northeast side of Indianapolis. And he’s not preparing for a test, he’s trying to solve a problem.

“We definitely want to know every detail,” Reddicks says. “We don’t know where this is coming from.”

He’s talking about an issue facing his and at least 22 other charter schools across the state – a funding issue. Schools of all kinds have been keeping an especially close eye on their budgets since the General Assembly tweaked the school funding formula during the 2015 “education session.” There are a lot of moving parts, and in some cases the federal government gets involved, which can add another layer of confusion.

That seems to be the case with the issue Reddicks is addressing: Title I funding. A number of charter schools saw a significant drop in their Title I allocations this year – while in some cases, nearby traditional public schools saw an increase.

But it’s not as simple as comparing apples to apples, and the math involved is confusing to many. And as with almost anything involving charter schools, it’s a touchy subject.

- Tiptoeing Around Title IIThere are a lot of moving parts to school budgets and plenty of different types of schools to deal with. And in some cases, the federal government gets involved, which adds another layer of confusion. That appears to be what’s happening with this year’s Title I funding situation in Indiana. A number of charter schools saw their Title I funds decrease this year – while in some cases, nearby traditional public schools saw an increase. But as StateImpact Indiana’s Rachel Morello reports, it’s not as simple as comparing apples to apples.Download

‘She helps build us up’

Clusters of Paramount first graders hunch over their desks, scribbling on subtraction worksheets on a sunny Thursday morning in Adam Freeman’s first grade class. Mr. Freeman weaves through the desks, reading the questions out loud and calling on students to write their solutions on the board.

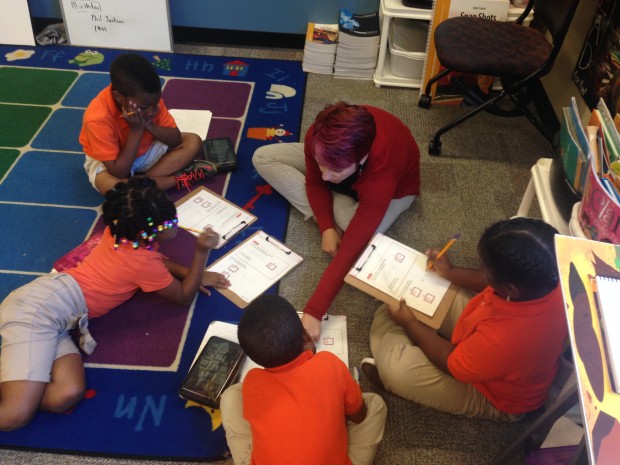

The students stay silent while he delivers his lesson, but upon a close listen, one can hear whispers floating from the front corner of the room. That’s Freeman’s Title I aide, Melodi Miller. She’s curled up on the floor, circled by four students. They’re working on the same worksheet as the rest of the class, but Miller is acting as their interpreter – explaining Freeman’s directions in different terms and giving them a little extra help to keep them up-to-speed.

“It’s just trying to figure out ways to get them to make those connections that we all have to make to learn,” Miller explains. “Kids are kids, the kids I’m working with just struggle a little more.”

Title I is a federal program that serves kids who generally come from low-income families, and therefore haven’t always had access to the same resources as some of their peers. This applies to about one-third of the students who attend Paramount.

Students like Deashia Warren, a fourth grader at Paramount who talks about her instructional assistant, Ms. Bowling, as if she’s a superhero.

“She always helps us do math facts so we won’t fail and then think we don’t know how to do stuff,” Deashia explains. “She helps build us up and try again.”

Melodi Miller, a Title I instructional assistant at the Paramount School of Excellence, helps lead her students during a math lesson. (Photo Credit: Rachel Morello/StateImpact Indiana)

Bowling and Miller are two of Paramount’s four Title I instructors. Each splits her time among two grade levels, but that hasn’t always been the case. Just last year, Paramount had seven Title I aides: one for each grade level K-5, and one in middle school. But the school lost $68,000 in Title I funds this year – 12 percent of the previous year’s allocation, to be exact. That represents about 10 percent of the school’s annual income.

“My day is just booked, a half-hour with each group from 8 o’clock to 2:30,” Miller says. “It’s just a busy, full day.”

Busier schedules mean less time devoted to each student, and more pressure on teachers. Freeman acknowledges Miller’s presence in his classroom during math and language arts lessons allows him to focus on teaching at the appropriate readiness level.

“When she’s not in the room, it’s a little more of a struggle,” Freeman says. “Those students end up not getting that targeted instruction as much.”

And that targeted instruction has been working at Paramount. Since the school opened in 2010, administrators have seen steady growth from the kids performing in the lowest 25 percent, something Reddicks attributes to the interventions Title I resources provide.

“We can’t say that’s 100 percent due to our targeted instruction to that population, but we can say that we target that population with remediation, differentiation and extra [instructional assistants] to help them out nonstop, so it has to play a role,” Reddicks says.

Confusion over cuts: What’s the formula?

Along with Paramount’s thriving Title I program, the school’s total student population is growing and free- and reduced-price lunch numbers remain steady at about 90 percent. Usually those are the indicators used to calculate school funding, so it doesn’t make sense to Reddick why his school is losing money – especially when compared to Indy’s biggest public school district, IPS, which received an eight percent increase in its Title I funds.

This in particular confused Reddicks along with several other Indy-based charters, some of which have been questioning the Indiana Department of Education about the matter since they received their allocations in May.

“How come if all of our students would otherwise be going to IPS, they’re not getting funded at the same amount from the federal government?” Reddicks wonders.

The answer is unclear. That’s because, to many, the formula for calculating Title I allocations in Indiana is also unclear.

—Chad Lochmiller, Assistant Professor, IU School of Education

IDOE spokesman Daniel Altman says the state saw an overall reduction in Title I funds this year of about $3.5 million. He adds that with respect to Paramount, the school’s Title I pot shrunk this year due to a reduction in their census poverty count – an explanation the IDOE offered to other charters, as well.

The third explanation involved a piece of the federal Title I regulation that the IDOE said does not apply to public charter schools: “Hold Harmless.”

This provision states a school can only lose so much funding from the previous year. How much they retain depends on what their student population looks like. For a school in high poverty like Paramount, the most they’re supposed to lose is 5 percent. That is, if it fits the definition of the type of institution hold harmless applies to.

Here’s what the federal statute says:

The purpose of this title is to ensure that all children have a fair, equal, and significant opportunity to obtain a high-quality education and reach, at a minimum, proficiency on challenging State academic achievement standards and state academic assessments. This purpose can be accomplished by…holding schools, local educational agencies, and States accountable for improving the academic achievement of all students, and identifying and turning around low-performing schools that have failed to provide a high-quality education to their students…

It’s the term “local education agency,” or LEA, that’s clouding the situation.

Chad Lochmiller, an assistant professor of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at the Indiana University School of Education, says LEAs are typically local school corporations or other types of educational institutions, including charters.

“They are viewed as an LEA that is comparable to a local school corporation,” Lochmiller offers. “They may not be part of a school corporation, but they’re going to have all of the same administrative responsibilities, opportunities to participate in Title I, reporting requirements – but they are actually treated as kind of their own school corporation in the eyes of the state.”

That sounds right to Michelle McKeown, interim director for Indiana’s Charter School Board. She says it falls to the nation’s top schools chief, U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan, and his department to provide some clarity on this point.

“I would love to ask Secretary Duncan whether the plain language in the regulation regarding hold harmless applies to public charter school LEAs in the state of Indiana,” McKeown ponders.

So, StateImpact asked him just that. He was in town for a visit to Purdue University last week.

“I would have to get the details,” Duncan responded. “Public schools are public schools in our eyes, whether it’s a traditional or a magnet or a charter, we’re pretty agnostic on that. We can have our staff look at the details.”

The U.S. Department of Education has yet to provide further guidance on the issue, but sources say they are looking into what next steps are required. Whatever they say will dictate how Indiana makes allocations. While the feds calculate funds for traditional LEA’s, Altman says the IDOE makes charter school appropriations based on federal guidance.

Did schools report their data wrong?

Yet another explanation the IDOE offered local charters is that the mishap may have been an error on the schools’ part.

A few days after the issue gained widespread attention through an Indianapolis Business Journal story, the department sent a letter to a handful of charter directors asking them to acknowledge that they had submitted incorrect data in their Title I requests for the 2015-16 school year.

“‘Please sign that away, that you actually made a mistake, and send that back to us’,” Reddicks paraphrases. “It’s an uncomfortable letter to read, and it’s hard to believe that someone at the state level actually put pen to ink in that response.”

IDOE Letter To Charter Schools

Chad Lochmiller says it’s not a regular occurrence that schools would submit flawed applications, or that the IDOE would approve them blindly. He says instead, this could be an issue of misunderstanding of how a school intends to use Title I funds.

“The way that Title I was set up, it was always intended to supplement, not supplant, basic education funding,” Lochmiller explains. “What happens is that many times, LEAs make decisions that sometimes confuse that understanding.”

“It sounds like there may have been some surprise involved because schools may have been banking on that funding over multiple years,” Lochmiller relays. “Is that then making it part of their basic education program, or is it actually just a continuing supplement that they’re using based on their student needs? That’s really unclear, but it’s a point that merits further distinction.”

Reddicks says this is not the case at Paramount.

“We’re not just taking federal money and offsetting our expenses with it,” Reddicks says. “We’re taking federal money and making a difference.”

—Tommy Reddicks, Executive Director, Paramount School of Excellence

But it’s a plausible argument – just a few miles east of Paramount, that’s exactly how the Speedway school district uses its own Title I money. Assistant Superintendent Patti Bock says the school funds school-wide instructional coaches who can support every teacher and whose services impacts all children, not just those identified for Title I services.

That’s because Speedway is a district of “school-wide” Title I programs – where the services benefit everyone – as opposed to a “targeted” program, whose Title money is funneled into services specifically for the identified students. Which program a school falls under depends on its count of students who qualify for free- and reduced-price lunch.

And it’s possible some schools aren’t aware when they’ve crossed from one category to the other. For example, schools in high-need areas similar to Paramount might not have an exact FRL count, since under UDSA guidelines their entire population can qualify for free meals if the school serves a population that has over 40 percent living in poverty.

“Usually a public school, from year to year they’re pretty stable,” Lochmiller says. “A charter school very much has fluctuations depending on who’s choosing to go there, what their characteristics are…and whether or not there was an administrative error in terms of reporting that information, all of those things come into play.”

Questions of intent

It’s impossible to talk about the current predicament Indiana charters find themselves in without getting into the usual back-and-forth over the charters’ place in the educational landscape.

It’s not a new issue – public school advocates have decried what they the privatization of education since the first charters appeared in Minnesota in 1991, while supporters have argued parents should have the ability to choose where to send their kids.

There are countless examples of folks calling the legality of charter schools into question. Most recently, the Washington Supreme Court ruled that the state’s charter school law is unconstitutional because in their view, charters are not considered public schools.

Charters have also been at the center of a handful of headline-making scandals in the recent past. Just this summer, the Ohio Department of Education’s charter oversight office came under fire for allegations of data manipulation. The same thing happened right here in Indiana, under former state schools chief Tony Bennett.

It’s an issue that draws clear dividing lines between Republicans and Democrats, and there’s no better example of that than right here in the state of Indiana, which boasts one of the nation’s largest voucher programs.

The Paramount School of Excellence serves 651 kids, about one-third of whom are identified for Title I services. (Photo Credit: Rachel Morello/StateImpact Indiana)

That could explain why some have accused Indiana’s DOE – headed by Democratic state Superintendent Glenda Ritz – of playing party politics by favoring traditional public schools over charters in distributing Title I funds. Two Republican Indiana congressmen – Reps. Luke Messer and Todd Rokita – sent Ritz a letter Monday insisting she explain why her department had treated the state’s charters “unfairly.”

But is this really the case?

“We don’t see it as malicious,” says Emily Richardson, McKeown’s colleague and director of school performance for the ICSB. “We don’t want to think that anyone did this based on perception, we’re just really trying to explain it. It’s just, we don’t have the information that is necessary.”

Tommy Reddicks agrees that more information is needed, but adds that he hopes the higher-ups on the state and federal levels realize that his school shares the same kids – and therefore the same needs – as nearby public schools.

“I think our greater fear is that we’re moving the wrong direction when it comes to creating a level playing field between traditional public schools and public charters,” Reddicks says. “My fear is that there’s still some backlash happening at higher levels stopping us from making those great transitions.”

Ideally, a solution or explanation for this Title I confusion will come soon – the state is already working on gathering data for the feds that will determine next year’s Title I allocations.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download