Meet The First Year Teachers

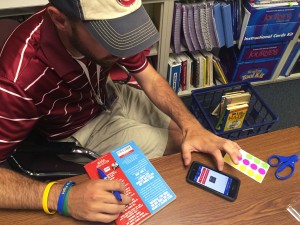

Gabe Hoffman will teach third grade at Nora Elementary School in Indianapolis. This summer, he’s spent a lot of time organizing his class library. (Photo Credit: Claire McInerny/StateImpact Indiana)

Think about the teachers you had as a kid. How many of them had been teaching for more than 10 years, 20 years, even 30 years? Quite a few probably, because that’s how the profession used to work.

But in the last 10 years, that’s changed, with 40 to 50 percent of new teachers not making it past their fifth year.

So what is it like to be a new teacher? What happens in classrooms that cause half of new teachers to leave and what makes the other half stay?

Over the next year, I will follow three teachers to learn about what makes their first year challenging, what is different than they expected and what makes all the time and hard work worth it.

But first, the problem

It’s graduation day for students at Indiana University’s School of Education.

Lines of gown-clad future teachers slowly make their way across the stage. They smile at their families and friends. A few have decorated their caps to look like chalkboards.

Right now, they’re excited to become teachers. But if statistics hold true, in just five years, half of them will be in a new profession.

- Meet The Three First Year TeachersOver the next year, StateImpact Indiana reporter Claire McInerny will follow three first year teachers to see the ups and downs of their first year in the classroom. Today she introduces you to the teachers.Download

“And so that’s kind of alarming to see,” University of Pennsylvania professor Richard Ingersoll says. “The rates were always high but they [have] slowly but surely been getting a little higher.”

Ingersoll researches teacher retention and says more teachers are entering the classroom. They just aren’t sticking around. He says while it’s easy to say teachers aren’t staying in the profession because of the increased accountability created through No Child Left Behind, including pressure to make sure students perform well on standardized tests and those scores being linked to teacher evaluations, it’s more complicated than that.

“If we just all of a sudden hold schools accountable but we don’t give teachers the tools to meet the bar so to speak then we have higher turnover,” Ingersoll says. “It turns out the most important of these tools is discretion, leeway and autonomy in the classroom. Don’t micromanage the teachers, it turns out that’s the leading factor.”

Chris Conway: The Suburban Math Teacher

Even before they begin setting up their classrooms for the upcoming school year, these teachers feel the weight that comes with lack of experience.

“I can see some parents not wanting to listen to a 23-year-old kid that just got out of college because they’re going to think they know what’s best for their child,” says Chris Conway. He’ll be teaching at Riverside Intermediate School in Fishers, a suburb of Indianapolis. “But I’ve kind of talked to other teachers about it and they said at the end of the day you’re the teacher and you know what’s best for them in the classroom and that’s what you have to do.”

Relying on other, more experienced teachers is one part of Conway’s strategy for surviving this first year. For example, he’s been stressing about dealing with parents, getting lessons prepared and prepping his room. But just the other day another teacher told him his biggest headache that first week will likely be getting kids used to their lockers.

Conway did his student teaching at Riverside and then substitute taught during a maternity leave at the end of the year, so he feels comfortable in the building.

“Other than that I’m just nervous about doing a good job,” he says. “I’m in charge of 60 kids and them learning and getting the scores they need to.”

Gabe Hoffman: Learning in the city

Fifteen minutes away from Conway’s classroom in the suburbs, Gabe Hoffman is setting up his classroom at Nora Elementary in Washington Township Schools in Indianapolis.

Gabe Hoffman organizes his class library by reading level. Hoffman is a first year teacher and will teach third grade. (Photo Credit: Claire McInerny/StateImpact Indiana)

“At the back of the room I have a little reading corner set up for the kids that they can go to,” he says.

Reading will be a huge focus for Hoffman this year, because his students will take the ISTEP+ for the first time, a high-pressure situation for a new teacher – and Hoffman even has other circumstances to add to that stress.

“The group coming in next year has done traditionally low on testing and scores, so they kind of told me to expect a group that is a challenge in that regard,” Hoffman says.

And Hoffman will likely deal with other issues that stem from being in an urban school, like poverty or behavior problems. Nora is also unique in that it has one of the highest populations of English language learners, so Hoffman expects to have at least a few ELL kids in his class this year.

With all of this on his mind, the first day of school is weighing on him heavily.

“I’m a little nervous because we talked about how crucial that first day and that first week are so it kind of made me a little anxious,” he says. “Knowing that, ok, I need to make sure to get things done the right way this first week in order to set things up for the rest of the year.”

Sara Draper: Second Grade On Quiet Streets

Sara Draper cuts butcher paper for a bulletin board outside her classroom. Draper will teach second grade at Helmsberg Elementary School in Brown County. (Photo Credit: Claire McInerny/StateImpact Indiana)

Helmsberg Elementary in Brown County is at the end of a windy, two-lane road through the wooded areas of Brown County, a stark difference from the schools near Indianapolis. It’s surrounded by trees, and standing in the parking lot on a recent Tuesday morning all you can hear are birds chirping.

“You can go 10 minutes without seeing a car,” says Sara Draper, who will teach second grade at Helsberg this year.

Unlike Conway and Hoffman who have the big picture concerns on their mind, Draper is thinking her way through some pretty specific scenarios.

“For some reason I have this huge fear of someone throwing up everywhere and me not knowing what to do,” Draper says.

Vomit or not, Draper is downright giddy to teach second grade. Regardless of all the change she’s facing this year, she’s looking forward to growing as a teacher and finding her groove in the classroom.

“I’m excited about that first moment where I feel like I’m really confident and I know what I’m doing,” she says.

But before any of these teachers will experience that moment, or any memorable teaching experiences, they must tackle the next biggest hurdle: the first day of school.