Once Common, Graduation Waivers Now A Last Resort At IPS

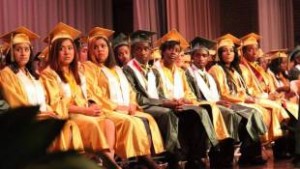

Indianapolis Public Schools students at a commencement ceremony on June 9, 2015. (Photo Credit: Indianapolis Public Schools)

Three years ago Nacala Koulou passed the required Algebra I end of course exam but since 10th grade, she struggled to pass the equivalent English exam to earn a high school diploma.

Without passing that test Koulou, who has a two-month-old daughter, had few options: be denied a high school diploma or hit the books.

Unlike the 1,000 or so Indianapolis Public School students in past years who got waivers from passing the tests – that option wasn’t likely.

In 2011 more than a quarter of Indianapolis Public School graduates were granted a waiver – a credential that likely blocks a student from attending most four-year colleges, such as Purdue and Indiana universities, and limits the amount of student aid available for higher education.

But area school districts are now focusing more-than-ever to ensure most students pass these basic exams. So far, for IPS, the efforts are working.

In 2014 only 6.9 percent of IPS students graduated with waivers – a rate slightly better than the state’s average of 7.4 percent. District leaders hope to chop that amount in half for Koulou’s Class of 2015

“I passed my ECA math but my English I didn’t because I fall asleep when I do computer tests,” said Koulou, an Arsenal Tech senior, last week. “I have to focus on the main points of the story. You read and you forget. You have to remember what you read.”

- 'I Deserve This'Like many school districts across the state, Indianapolis Public Schools are working to lessen the number of graduation waivers students receive. WFYI’s Eric Weddle reports.Download

A fine line

Granting graduation waivers were once the norm at IPS and other school across the state that readily gave diplomas to students without passing basic math and English exams.

In 2013 lawmakers sought to clamp down on waivers by revamping remediation policies and stopping students who use a waiver from receiving state financial aid for college.

IPS Director of Student Services Deborah Leser oversees the effort to cut waivers at the district. Yet doing so, she says, can be like walking a fine line.

“Do you look at it as: you just want every student to get their diploma because that’s important and we know it’s an important step for their employment and those kind of things,” Leser said. “Or do you hold the bar and the expectation to make sure when those students get out of high school they are prepared for the next steps.”

When efforts began to reduce waivers, Leser said there were concerns that could lead to a trend of fewer graduates. IPS did face a drop in graduates in 2012 but that has rebounded to 71.5 percent last year. In 2007, less than half of high school students graduated in four years.

It’s not realistic for all students to graduate without a waiver, Leser said, as some special education students and English-language learners can’t overcome the exam even while making academic advances during their high school years.

Leser says teachers review student test scores to pinpoint gaps, ask about anxiety during exams and why they think their having problems.

“Put that all together and really look at each child and find what do we need to do, what is the recipe going to be for this student you – there is no fix all,” she said. “You really have to just work with them one-on-one.”

Funds for remediation, alternative education and summer school are used to support various programs across the district to help students pass ECAs.

Yet, Leser said, teachers, administrators and staff put in many more additional hours “without compensation” to get the job done.

Working without extra pay sometimes, is just part of the job, said Edith Preddie-St.Clair. She tutors students after school to prepare them to retake the 10th grade English end of course exam.

Preddie-St.Clair said many factors make it difficult for some students to pass the the tests, such as not having regular access to computers.

“A lot of the exam is not culturally relevant to all kids. You have to remember, that some students living in a different place, if you talk to them about certain things, they know,” she said. “But depending on home, environment for other kids, they may look at it a different way.”

Getting over the bar

The growing immigrant student population in the Indianapolis-area is also straining districts trying to reduce their waivers.

Since 2001, more than 2,000 refugees have enrolled in Perry Township schools, most are Chin, a Burmese ethnic minority. In the past few years, graduation waivers at Perry have been at 15 percent or higher – that was the highest rate among Indy-area public schools last year.

“So when we get refugee students coming to us with little or no English background that are entering our secondary schools – say 7th grade through 12th grade – is really a challenge for us to get them over the bar of that English 10 exam,” said Robert Bohannon, Perry Township Schools assistant superintendent.

Bohannon says remediation programs and early intervention have lead to reducing waivers for general and special education students. English language learners, just like other students, who are granted a waiver have to pass an alternative assessment exam plus meet other benchmarks, he said.

Annually, Bohannon wants to see a 10 percent decrease in waivers for students in special education and non-native English speaking programs. For general education students, the goal is 25 percent reduction.

‘I deserve this’

There are two types of a waivers that students can receive: evidence based – meaning, they meet academic standards in the subject area not passed – and workforce waiver, which requires an industry certification.

To be considered for a waiver, students must have 95 percent attendance, earn a C average and take the end of course exam each time it is offered – three times per year.

Last fall Koulou spent four days a week after school working with Preddie-St.Clair before taking the English ECA exam.

Koulou learned strategies to answering questions about passages she read – an area she had struggled with before.

“It just now hit me that I am graduating. But when I sat in that chair, I said, yes I am ready to cross that stage,” she said. “I’m going to graduate. I put my sweat into this. I deserve this.”