Pre-K: How Does Indiana Compare On The National Scene?

The new year brings a fresh start, and nobody is more aware of impending changes than families in Allen, Lake, Marion and Vanderburgh counties.

Indiana’s first preschool pilot program begins in those four communities in January, when an anticipated 450 low-income four-year-olds will head off to school for the first time.

Forty others, plus the District of Columbia, already have state-funded pre-k. Indiana will become the 41st. President Obama has been pushing for more states to adopt preschool programs, and in doing so he’s been dropping names of states he sees as national examples, including Oklahoma, which was one of the first to offer free voluntary pre-k in 1998.

Approximately 46 percent of children across the country – approximately 3.7 million – attend preschool, according to data from the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

In the early stages of planning Indiana’s program, Melanie Brizzi of Indiana’s Family and Social Services Administration gave StateImpact a list of states she considered as models for the Hoosier state’s program.

“Minnesota, Florida, Ohio, Illinois – there’s an abundance of research material we can go to,” Brizzi said.

Let’s take a look at some of those states and see how Indiana compares.

- The ABCs of Pre-K in IndianaPlenty of states already have state-funded pre-k – 40 others, plus the District of Columbia, to be exact. So, StateImpact Indiana’s Rachel Morello reached out to educators in those states to gauge whether Indiana is starting off on the right track.Download

U.S. sees rise in programs, funding

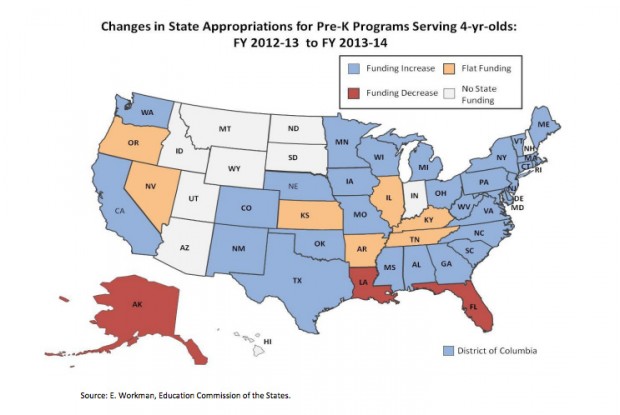

Each year, the Education Commission of the States compiles data about states’ spending on early education. This year, state investments total $6.3 billion, up from $5.6 billion last year.

Thirty-four states increased their funding from the previous year.

Bruce Atchison, the director of the Early Learning Institute at ECS, says this year saw a 54 percent increase from the 2013-14 school year.

“That included ten million dollars from Indiana, which previously we would have referred to as a ‘wilderness state,’ one of those state that wasn’t investing anything from their general fund in pre-k,” Atchison explains. “Momentum is building, as evidenced by the number of states that continue to invest in high-quality pre-k.”

Atchison says spending is just one factor leading to the rise of pre-k across the country.

“It is truly a non-partisan issue,” Atchison says. “Almost 70 percent of Americans now favor public funding for early childhood education programs, so the public will seems to be there. It’s the political will [that is still uncertain], and that’s going to vary from state to state.”

He adds that states that don’t yet fund pre-k – North Dakota, Idaho, South Dakota, and Montana, to name a few – can attribute the lack of pre-k dollars to attitudes in the state legislature.

“That attitude, often times, is ‘it is not the role of government to fund pre-k, that’s the role of the parent, that’s the role of the family,'” Atchison explains. “That’s often times why, I believe, these programs haven’t moved forward in certain states.”

As far as states that do pre-k well, Atchison points to Massachusetts, Colorado, and Georgia. But he says there is no one “model” community because everyone still has individual hurdles to overcome.

“I don’t think there is any one state, or even a top three, that I would say they do it best, because everyone is still grappling with issues,” Atchison says. “You can look at some place like Oklahoma, who is doing phenomenal work, but they grapple with their governance structure, which is a huge issue for so many states.

“I think there are states that are in the forefront, and then there are states that are following suit, and then of course there are those states that still have a ways to go.”

Florida: A state in the forefront

Florida’s program, Voluntary Pre-K (or VPK) has been in place and steadily growing since 2005. And as you might expect after ten years, Florida has pretty much got it down.

Tara Huls, VPK’s chief in the Florida Department of Education’s Office of Early Learning, says currently between 78 percent and 80 percent of the state’s 4-year-olds participate in the program.

“The first year of VPK we had around 50 percent of eligible 4-year-olds participate, so we had fewer providers as well, probably around 4,000,” Huls says. “The last three or four years it looks like it’s stabilizing, and the number of providers is fairly stable too.”

Children at Emerson Elementary School in Seymour participate in the Kindergarten prep program. (Photo Credit: Rachel Morello/StateImpact Indiana)

VPK is open to all 4-year-olds– unlike Indiana’s approach, which is targeted specifically at low-income families. Although it is essentially a universal program, Huls says state leaders chose to use the term ‘voluntary’ to ensure that families understand that it is not required.

Bruce Atchison says a universal model like Florida’s is the way of the future.

“The idea of voluntary pre-k universal programs is a direction this country needs to move,” Atchison says. “That way we will be reaching all of the underserved children, and the upper income people will hopefully be able to pay their own way as they currently do.”

Similar to Indiana, the Sunshine State allows pre-k providers to apply to be a part of the program, and around 6,500 have – a blend of public schools, private schools, faith-based and home care providers. Florida also has a kindergarten assessment that they use to gauge students’ progress. Indiana will have one of those, too.

Huls emphasizes the term “high-quality” when she talks about pre-k. She says she recommends Indiana focus on that aspect, too.

“Our program has always had very lofty, but achievable child performance standards, so what we expect from children when they’re leaving VPK,” Huls explains. “Part of how we look at high quality is that we have programs that are helping to prepare children across the board.”

Financial woes won’t stop Illinois

Illinois’ program, Preschool for All, looks a lot more like Indiana’s. Although it started as a universal program in 2006, it began to target low-income kids after the recession hit two years later.

Sara Slaughter, education director for the McCormick Foundation in Chicago, says the state has lost service to about 25,000 children with the change, but that has not affected the quality of what providers are able to offer.

Finances caused Illinois pre-k leaders to narrow the scope of the state’s program. (Photo Credit: 401 (K) 2012/Flickr)

“I think Illinois, despite serving fewer kids than we would like to be serving, we do have a very high quality program, our standards are high,” Slaughter says.

Bruce Atchison agrees.

“They have quality standards in place which, I can’t emphasize that enough,” Atchison says of Illinois’ pre-k efforts. “It’s not enough just to have a program and put money into these services. States need to have quality standards that – even if they don’t align with the Common Core state standards – they’re quality state standards that the state board has approved.”

Illinois didn’t make any funding increase in their pre-k programs this past session, but the state recently won a federal Preschool Expansion Grant, which will bring in $20 million dollars in 2015. The grant is also renewable for four more years.

“[The grant] is going to allow us to serve more 4-year-olds and do so in a comprehensive and high-quality way, so that’s very exciting despite our state’s own financial issues,” Slaughter says.

Indiana was eligible to apply for a similar grant through the U.S. Department of Education, but Governor Mike Pence decided not to apply earlier this fall.

With history as a guide, Slaughter says her advice to Hoosiers is to work with what you’ve got.

“When the money is spent, it first has to go to quality,” Slaughter says. “It’s no good to have a program that lacks the quality but reaches every kid. Start with that high quality, and then go for increasing the number of children.”

How does Indiana stack up?

[pullquote] Let’s do what’s best for our budget, what’s best for our families, but let’s look at what some other states have done. – Bruce Atchison, Education Commission of the States[/pullquote]

If ‘quality over quantity’ is the name of the game, then Indiana is on the right track. The FSSA is requiring interested providers to achieve Level 3 or 4 status on the state’s Paths the QUALITY ranking system. Only four counties are launching efforts in January – five, when Jackson County joins in next August.

Bruce Atchison says slow and steady wins the race.

“Let’s do what’s best for our budget, what’s best for our families, but let’s look at what some other states have done, what’s worked and then we can create the best policy based on the homework that we’ve done.”

Part of Indiana’s homework: a long-term study, which should help the state take what it learns this year and figure out how to move forward.

Atchison says he commends Gov. Pence and the state legislature for moving the program through.

“Ten million dollars is not chump change!” Atchison exclaims. “But [pre-k] is a hot issue politically, and we know from research that quality programming pays off in the long run. I think it’s a great beginning. It’s a whole lot better than nothing.”