How English Teachers Are Reacting To Common Core Nonfiction Requirement

Cowardly Lion / Wikimedia

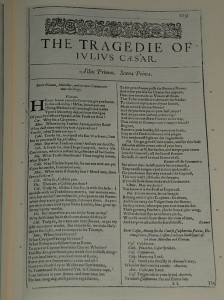

Some English teachers say they're dropping classic works like Shakespeare's 'Julius Caesar' to satisfy the Common Core's nonfiction requirement.

NPR took a look at the new Common Core literature requirements this weekend. As we’ve noted before, there’s debate about how the new standards’ emphasis on nonfiction will fit into high school English classrooms. From All Things Considered:

Of course, there’s only so much time in an academic year, and the Kentucky teacher NPR interviewed concedes that means some stories get abridged. Gunter’s students used to read “Julius Caesar.” Now they only read a few speeches from the Shakespeare play.Before Common Core, students in most high school English classes read mostly literature, but the reality now is that students must split their time between fiction and nonfiction. There are even some school districts where teachers have been asked to drop novels altogether to meet the new nonfiction requirements.

Despite some pushback, almost the entire country — 46 states and Washington, D.C. — have already signed on to the Common Core standards. While some states won’t adopt the guidelines for several years, others already have.

Angela Gunter teaches English at Daviess County High School in Owensboro, Ky., the first state to adopt the guidelines. She says that at first, many of her colleagues opposed the changes.

“We English teachers love our literature, and the greater emphasis on nonfiction texts was uncomfortable for some of us,” she says. But now, her students actually like it. She kept them in the loop during the transition, beginning by showing them their own reading-level scores.

But an architect of the new, nationally-crafted academic standards says English teachers don’t have to abandon their favorite works in favor of nonfiction.

“There’s a disproportionate amount of anxiety,” David Coleman told The Washington Post last month.

Coleman says the nonfiction requirement includes texts read in all subjects, not just English. That means exposure to Lincoln’s second inaugural address or Martin Luther King Jr.’s letter from the Birmingham jail in history class would help high school teachers reach the 70 percent nonfiction threshold.

Here’s the footnote on reading informational texts in other subjects as it appears in the Common Core standards:

The percentages on the table reflect the sum of student reading, not just reading in ELA settings. Teachers of senior English classes, for example, are not required to devote 70 percent of reading to informational texts. Rather, 70 percent of student reading across the grade should be informational.

If you’re trying to find it yourself, it’s at the bottom of page 5. (The Educated Reporter‘s Emily Richmond thinks it’s a strange place to bury such critical instructions.)

As state lawmakers debate whether Indiana should stay the course with the Common Core or withdraw from the new standards, we’ve heard anecdotal evidence from parents that reading lists are changing in Indiana classrooms.

English teachers, have you changed what texts you teach as a result of the new standards?