In Smaller Schools, State Letter Grades See Big Swings Year-To-Year

North White School Corporation

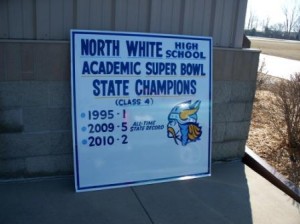

Several North White School Corporation schools received an A for the last two years in spite of a series of teacher layoffs and school closures.

Out of the 94 schools in Indiana with fewer than 200 students, eight saw a complete reversal of their letter grade from either A to F or F to A. 24 saw a shift of at least three letter grades– for example, from a B to an F.

How useful are those results?

We spoke with a pair of experts about how small class sizes, lack of resources and sometimes simple geography can work against small schools trying to compete in an increasingly results-driven educational environment.

“With these small schools, you have the issue of outliers. If a district gains or loses students or a few students have a bad year, then you could see dramatic fluctuations in assessment scores,” says Indiana University Education Professor Leslie Rutkowski.

The state’s assessment model is based on only two indicators. For elementary schools, this means ISTEP+ scores. In high school, this means a test called “end of course assessments” or ECA’s. Rutkowski says these tests are designed to evaluate everything from the needs of an individual student to teacher performance. The final score is not necessarily important; the point of the test is to provide guidance in determining areas of improvement.

Federal No Child Left Behind regulations have mechanisms for handling different sample sizes. For example, the law allows states to create broader targets for schools with fewer students. In other words, a school with low enrollment would receive an A if more than 80 percent of students passed the ISTEP+ test, while a school with a larger enrollment would be required to pass more than 90 percent of its students. It also allows states to average scores over time if a single year does not provide enough data to generate a reliable assessment.

However, Indiana does not currently utilize any of these systems. Under Public Law 221, a school must have fewer than 30 students to qualify for these kinds of modifications. Currently, the smallest school tracked by the Indiana Department of Education has 42 students.

How Does It Work?

To answer this question, it might be useful to look at how the state’s assessment model is structured. As we’ve already mentioned, the state’s A-F scale uses one of two sets of tests to assign a letter grade to schools based on how well students perform. The ISTEP+ is designed to cover basic concepts in elementary and middle school- primarily reading and math. End of Course Assessments measure high school proficiency in two areas: first year algebra and 10th grade English language arts. Two factors are taken into consideration when determining the final letter grade:

1. How well did students perform on the test?

In Indiana, schools with high performing students receive good letter grades. Schools where students perform poorly receive poor letter grades. So a school where 95 percent of students pass the ISTEP+ test receives an A. A school where 25 percent of students pass the ISTEP+ receives an F. All of this is true, unless…

2. Schools make sufficient improvements to their test scores.

If a school which performs poorly on standardized test makes serious improvements over the course of several years, then its rewarded with a higher letter grade. For example, the school with the 25 percent passage rate might receive a grade of B, if that percentage includes an improvement of at least five percent.

The provisions of this system are set in the statutory language of Public Law 221. The system is based on the idea that schools should continuously improve towards the goal of higher than 90 percent performance. The federal No Child Left Behind law is structured in a similar manner, but the eventual goal is 100 percent test proficiency for all schools.

What Is The Impact?

David Rutkowski says the letter grades are only partially meant to guide schools.

“They are at least as much targeted at allowing the public to easily see how well a school is doing,” says David Rutkowski.

Still, the letter grade assessments come with a number of actual consequences for both schools and communities. As we’ve reported, businesses sometimes use the scores to evaluate the quality of education in an area. The state also looks at letter grades when deciding which schools need intervention and which schools are doing well.

There have been two cases in the last year where school administrators have lost their jobs largely based on bad letter grades. Indianapolis’s largest district lost four schools to the state in August. The Gary Community School Corporation saw a similar take over of one of its alternative schools. Admittedly, both of these cases involve urban districts with long entrenched problems with poverty and academic under-performance.

Still, Leslie Rutkowski says these districts aren’t so different than many small or rural schools in the state.

“It doesn’t matter how good your teachers are or how good your school is, a student who is worried about losing their home is not going to consistently perform well on standardized test.”

In many cases, the state’s smallest schools are located in high poverty areas. For example, all of the schools in Greene County contend with a 16 percent poverty rate. Residents in sparsely populated Sullivan County face a poverty rate approaching 20 percent. That’s only three percentage points lower than Gary, which tops the list of Indiana’s poorest cities at 23 percent.