How Indiana's Neighbor States Handle Referendums

Ben Skirvin

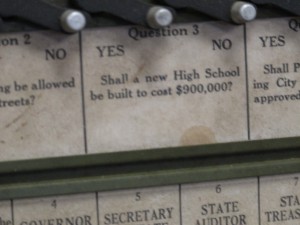

This is a ballot from 1956. Included is a request for $900,000 for construction of a new school facility.

There is only one way for schools in Indiana to raise money: ask voters to increase their property tax bill. This process is relatively new for Hoosiers — districts have only been turning to the ballot box for about two years. But neighboring states like Illinois, Michigan and particularly Ohio have had referendum-funded schools for decades.

Outside a truck stop just over the Ohio border there is a sign reading “Vote for Miami Valley Career Technology Center – Keep Education for Jobs.”

This is one of about a hundred similar signs in the area. Currently, 146 districts in the state are attempting to pass a funding referendum or (as they’re called in Ohio) levies.

The administrative offices of the Mad River School Corporation are located just outside of Dayton. In the corner of an office marked with a sign reading “Mailroom and Public Relations,” there’s an old ballot on a machine from 1956. Right alongside the name “Dwight D. Eisenhower” is a school ballot question asking for additional money. In fact, the district’s treasurer says they’ve been asking voters for money practically since the state was formed. One key in getting levies passed, experts say, is be open.

Terry Tosconi has worked on the Mad River parent committee behind four different levies. She says, when it comes to a referendum, silence is far from golden.

“It worked the first time,” said Toscani. “Just targeting certain things because you wanted to make sure that it passed. But it’s not always gonna work every time and it’s actually gonna create some animosity and people are gonna become bitter- like why are we not important enough that we are given information or things are being handed out in our neighborhood.”

Secondly, districts must consider their image. Indiana’s tax structure is complicated. Corporations are funded by the state, but they don’t just receive a big pile of money, which can be spent as the school board sees fit. Dollars allocated for construction must be spent on construction, not on teachers. Mad River treasurer Jerry Ellender says frequently voters have a difficult time following the money.

“Handle some of those smartly, like not going out and doing some of those big capital projects when you’re trying to pass an operating levy so you don’t exacerbate the confusion,” said Ellender.

And sometimes, school districts must be persistent. Mad River offered the exact same levy during a special election in August. It failed. Rather than give up, officials will try again this month. If that fails, they may try again in May. Referendum volunteer Terry Toscani says ballot initiatives fail so often she’s actually forgotten how many campaigns she’s worked on.

So how does it all work?

In the both Indiana and Ohio, there are limitations on how much a district can collect in property tax revenue. The only way to exceed these limits is to turn to voters. This system was established to give voters direct control over their taxes.

Ohio Supreme Court

Click here to download one of the rulings declaring Ohio's school funding system unconstitutional

But experts say it may not be legal.

David Varda has worked in school finance in Ohio since the middle nineteen sixties. He’s now head of the Ohio Association of School Business Officers.

“We had a challenge to our school funding system,” said Varda. “It said we were over reliant on property tax.”

According to four separate Ohio Supreme Court rulings, referendums do not provide equal opportunities to all schools or students. Because homes in wealthier districts are worth more, the tax base is greater. Thus, those districts are able to collect more money — and at a lower tax rate — than districts in economically depressed areas.

Indiana’s constitution does not include the same stringent assurances of equal funding for all schools. However, other states have seen similar lawsuits. Detroit schools, for example, sued the state of Michigan citing large swaths of abandon or worthless property.