Have Colleges And Schools Set The Bar Too Low For Teachers?

Teachers aren’t held to rigorous standards, judging from the grades prospective teachers receive in college and their evaluations once they enter the classroom.

So argues a new report, sponsored by the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute, which specifically singles out Indiana University’s education department for giving out an overwhelming majority of its students A’s. (Sound familiar? As we reported last month, more than 68 percent of all the grades professors award in IU education department classes are A’s. Only seven of IU’s 68 departments give out A’s at a higher rate.)

The report, of course, assumes that giving out A’s at these rates shows standards in these classes are low — which, as we also pointed out last month, isn’t necessarily true. It’s worth noting, too, that Purdue University’s Department of Education Studies gives an average of 32.5 percent of its students A’s, one of the lower averages among Purdue departments.

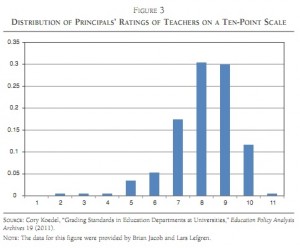

But the report’s criticisms don’t end with college classrooms. Report author and University of Missouri economics professor Cory Koedel, cites a survey that finds, when asked to rate their teachers on a ten-point scale, school principals gave more than 70 percent of their teaching staff an “8” or higher.

So is this evidence teachers are coddled by their education professors and then their professional evaluators? Koedel argues ‘yes, it is’:

The education sector is notoriously ineffective at identifying high- and low-quality workers, making it difficult for the labor market to penalize students from education departments that produce low-quality teachers. The culture of low standards in education is partly to blame, as those within the education establishment have shown little interest in distinguishing good teachers from mediocre teachers, but why can K–12 schools get away with not distinguishing high-quality workers from low quality workers? What makes education different? The answer is that there is not a competitive market forcing schools and districts to be efficient. For example, if a school hires mediocre teachers and produces mediocre outputs year after year, there is no mechanism to meaningfully penalize the school or its workers.

A few caveats: The ratings principals offered for the study Koedel cites don’t necessarily reflect the actual evaluations they gave teachers. And, as Alfie Kohn notes (we cited his argument in our July post) it isn’t necessarily fair to say a higher grade indicates colleges have set the bar too low for teachers:

The burden rests with critics to demonstrate that those higher grades are undeserved, and one can cite any number of alternative explanations. Maybe students are turning in better assignments. Maybe instructors used to be too stingy with their marks and have become more reasonable. Maybe the concept of assessment itself has evolved, so that today it is more a means for allowing students to demonstrate what they know rather than for sorting them or “catching them out.” (The real question, then, is why we spent so many years trying to make good students look bad)…

The bottom line: No one has ever demonstrated that students today get A’s for the same work that used to receive B’s or C’s. We simply do not have the data to support such a claim.

The study’s findings, however, might offer some insights for Indiana school districts, which are beginning to figure out how to implement state-mandated teacher evaluation policies and merit pay plans.

While the state sets some “guidelines and guardrails” for how the new systems (which are required in teacher contracts beginning with the 2012-2013 school year) will work, local districts get to determine who evaluates teachers and how to rate them in the state’s “effective/ineffective” scoring bracket. (More on that system here.)

So do you believe this survey? And given its findings, do you think districts are going to be able to give accurate teacher ratings when the evaluation system becomes mandatory?