Reporter’s Notebook: Covering English Learners Across Indiana In 2016

Elias Rojas is a first grade teacher at West Noble Primary school in Ligonier. As one of the school’s few bilingual teachers, he volunteered to participate in the school\\’s new dual language immersion program. (photo credit: Claire McInerny/Indiana Public Broadcasting).

At the very beginning of 2016, I wanted to follow up on a school funding change that went into place the year before. A previous school funding formula gave schools more money to educate high-need students, like students in special education, students who are English learners and low-income students. But, in an attempt to distribute school funding more equally, the new formula took much of that money away.

I traveled to Goshen Community Schools to look at how these cuts were affecting a district where a third of the students need English learning services. I spent a lot of time with the district’s Chief Financial Officer, and I didn’t expect it to be an emotional interview. But it was. The district lost a lot of money through the new funding formula, and he worried they might have to scale back services.

- One Year Later, The Change In School Funding Puts One English Language Program In JeopardyDuring last year’s legislative session, the General Assembly changed the school funding formula, giving every school district a similar amount of money. For schools with a lot of kids living in poverty or qualifying as English Language Learners, this funding change is having negative consequences.Download

This story drew me into a topic I hadn’t covered closely yet – English language learning.

When I looked at the data, school districts with the highest percentage of English learners were mostly concentrated in rural areas, and I saw that this was an issue that wasn’t being covered. I knew small, rural school districts were also facing disproportionately larger budget problems, and English learning programs are expensive. I was also interested in the social reactions to this population, as it is a growing percentage of residents in small towns.

I became so invested that I applied and got a fellowship with the Institute for Justice in Journalism, whose 2016 program was focused on stories around immigrant children. I pitched a series of stories on different school districts serving the growing English learner population in rural Indiana.

One of my first stops was Frankfort, where the schools serve the largest percentage of English Learners in the state. Eight teachers are trying to provide English learning services to 800 kids.

- As English Learners Continue To Grow In Indiana, How Are Schools Keeping UpEnglish learners continue to grow as a population in Indiana’s schools, many educators are struggling to keep up with the educational needs of these students.Download

Many small districts face this challenge. It often means the dedicated EL teachers don’t get as much time with the kids as they’d like:

Other teachers say they get pulled away from working with English learning students to proctor ISTEP+ exams or do lunch duty. And they all say the schools need more dedicated, certified EL teachers. But Frankfort’s Director of English Learning, Lori North, says that’s a tough ask right now.

“We had teacher cuts this year so it’s really hard for me to go and say ‘I need more EL teachers when they’re cutting general education teachers,” North says.

Another place this reporting took me to was Columbus, Ind., a larger school district, but one where the English learner population was changing. The EL teachers in the district had typically served Spanish speaking students, but because of foreign businesses moving to Columbus, more and more Japanese students were enrolling in Columbus schools.

- As More Japanese Families Move to Columbus, The School District Forces Itself To AdaptListen to the radio version of this story here.Download

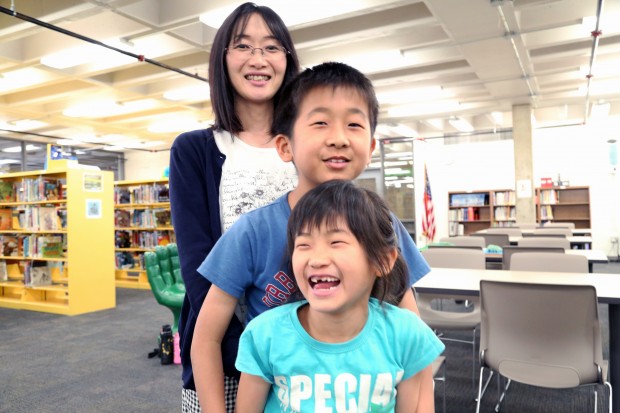

Hiroko Murabayashi moved to Columbus, Ind. from Japan in August with her husband and two kids. They came for her husband’s job at Enkei, a Japanese wheel company with a branch in Columbus. Her children, Yoki, 9, and Rico, 7, attend Southside Elementary school in the Bartholomew County School Corporation and receive English language services. When they started the year they didn’t speak any English. (Claire McInerny/Indiana Public Broadcasting)

It is hard to appeal to every student’s language and cultural needs. And this frustrates some parents, who want the teachers to give their children more one-on-one attention.

While in Columbus, I met Hiroko Murabayashi, a mother of two elementary school students. They only lived in Columbus for a few months, and she was hoping her kids would spent more time learning the mechanics of English and not as much in their general studies.

This tug of war between what a school is capable of doing and what is best for a student learning English was a theme. And it’s what made this topic so interesting.

Relative to other states, Indiana’s immigrant population is small, but it’s growing quickly. This tension is not going away.

And this is something I heard so often from teachers in these schools – they don’t feel supported. They say most of the legislators who are able to allocate funds to these programs don’t understand how much work it takes to learn English.

Another thing that came up again and again – once the EL students became proficient in English, they academically outperformed native English speakers.

My last story of this series took place in Ligonier, at West Noble Primary School. This school received a grant from the Indiana Department of Education to start a dual language program. This type of program requires teachers who speak two languages, because they will teach half of their lessons in one languages and half in another.

West Noble’s population is about half Latino, and many of the students were already bilingual.

- How Does Making Everyone Learn Two Languages Help English Learners?As the number of English learners grow in the state, schools are trying different programs to teach these students more effectively.Download

I loved rounding out the series with this story, because it showed a school that is able to embrace its diversity. When I spoke with the principal and a teacher for the dual language program, their goal is to break down social barriers and encourage all students to be bilingual.

“I want them to feel equipped with and have the mentality to have a diverse mentality,” first grade teacher Elias Rojas said. “To have them not see a minority and not say that’s a minority. That is a person.”