Homeless Children An Increasing Worry For Indiana School Districts

For more than a decade, the number of children living at or below the poverty line has steadily increased by about 1 percent a year. Census data show nearly one in five children in Indiana are living in households with income levels at 50 percent of the federal poverty level.

In Indiana’s schools, this translates into more per-pupil funding from the state from programs designed to educate children living in poverty. Across the state, more than 60,000 new students have been added to the free lunch program since 2008.

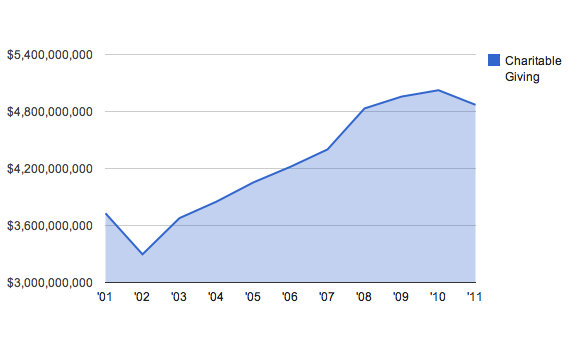

But as donations to charities designed to help these children level off, schools find themselves increasingly shouldering the burden of making sure these students have basic needs met.

Jordan Streep is 15-years-old. He’s a B student who likes computers, plans to run track and wants to study biology in college. He’s clean cut and well-spoken, the kind of kid you might expect to find living in a nice home in a nice suburban neighborhood. But Jordan’s living in a homeless shelter.

“It’s mostly the sounds of the kitchen that I notice at the shelter and the television, because that’s where most people spend their time.” Jordan says.

He’s been without a steady roof over his head since early September. Most of his life in Columbus, he bounced from apartment to apartment.

“Mostly apartments. We had a house once. But it was a rental,” he notes casually. “But the shelter’s nice. Clean and the people are OK.” He speaks frankly, with slow contemplation when the conversation strays over the rougher parts of his past. The state took him from his mother’s care when he was 9-years-old and placed him with his aunt and uncle in Bloomington.

He’s been fortunate to land here, where there are more resources than most place. Robust job growth and steady home values mean students in poverty usually have somewhere turn when the need a hot meal or a place to stay.

But Becky Rose, a social worker with the local school district, says this persistent issue of housing worries her.

“[Housing] is one of the biggest barriers they’re encountering,” she says. “We have lots of of families who are doubled up.”

The school keeps a couple of houses for families going through an emergency. In the past, these were used in cases of disaster, when homes burned down or were damaged by flooding. Increasingly, they are being used to house families driven to homelessness by financial rather than natural circumstances.

Rose may have good reason to be concerned. Even in Bloomington, long viewed as an oasis for the downtrodden, things might be getting tougher. According to the National Center for Charitable Statistics, Indiana’s human service charities are experiencing their first financial downturn since 2002, shedding nearly $200 million dollars since last year.

National Center For Charitable Statistics

The downturn at the top of the graph indicates the the first time since 2002 that Indiana has seen a downturn in social service giving

Even during the worst years of the financial crisis in 2008, even as unemployment hit a record high in 2009, even as the worst of the Great Recession rolled through Indiana, Hoosiers managed to find a way to dig a little deeper and give a little more.

But that trend has stopped.

Jordan takes it all in stride. In his relaxed, laconic manner, he describes staying at the shelter since early September, just before the start of the school year. New Hope Family Shelter only allows people to stay for 90 days, so he’s already past his deadline. When they finally have to leave, it’ll probably be another apartment. That’s a decision his aunt will have to make.

He’s new to the streets. From fifth grade through earlier this year he lived with his aunt and uncle in an apartment on Bloomington’s south side. Before that, he was in the care of his mentally handicapped mother living in Columbus with her and her boyfriend — an electrician from Franklin.

In some ways, he’s fortunate. Columbus, where he was raised, has seen the recent loss of one of its biggest charitable groups. The Irwin Sweeny Miller Foundation, an endowment worth more than $10 million, announced last January that it intends to dismantle it’s gift-giving operations in Columbus by the end of this year. The group is inextricably connected with nearly all of the city’s social service programing from the Foundation for Youth to Habitat for Humanities. This leaves major holes in the budgets of countless organizations tied to helping children and families in poverty.

Money Spent Per Pupil By Columbus Schools

| Year | Dollars Spent Per Pupil | Free Lunch Participation |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | $11,300 | 32% |

| 09 | $10,600 | 29% |

| 08 | $10,500 | 25% |

Indiana Department of Education

And who does that responsibility fall on? Schools. According to the Indiana Department of Education, Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation’s per pupil spending has increased dramatically over the last few years- jumping from $10,500 in 2006 to $11,300 in 2009. Much of that directed to support services like providing free lunches or financial assistance to children in poverty rather than towards the classroom.

The number of students on free lunch programs has gone up by more than 7 percent. And there is mounting evidence that more and more families are ending up in poverty. The the number of students taking part in a reduced lunch program has declined, while the number of students receiving free lunches has increased- meaning these children are moving down the income latter rather than up.