5 Years Later, State School Choice Looks Dramatically Different

Five years ago, the General Assembly created a school choice program to help low-income students get out of failing schools. Today, more middle class families and students who never attended public schools are using the vouchers. (Photo Credit: Claire McInerny/StateImpact Indiana)

Private schools are experiencing a surge in enrollment, in large part because of the state’s expanding voucher program.

When the program first passed in 2011, supporters said funding private school tuition would give poor kids in failing schools options to get a better education.

But a new report shows that as the program enters its fifth year, the cost to taxpayers and students has changed dramatically.

Indiana’s School Choice Program, From The Beginning

To understand the state’s school voucher program, officially called the Choice Scholarship Program, you have to sift through a lot of numbers. A good place to start: enrollment.

“Well it’s grown quite a bit, the number of students using the choice scholarship program increased a lot year over year, there’s no question about that,” says Chad Timmerman, education policy adviser to Gov. Mike Pence.

During the 2011-12 school year – the first year for the Choice Scholarship program – around 4,000 students enrolled. Last year, it was almost 30,000.

“Obviously with the doubling of students or whatever magnitude we’re growing, you’re obviously going to spend more on vouchers,” Timmerman says.

- When the General Assembly created a voucher program in 2011, the intention was to give low-income students “stuck” at failing public schools more choices when picking a school, by subsidizing private school tuition. But as the program evolved, more middle income families qualified for vouchers, and half of the students getting these state vouchers have never attended a public school.Download

On paper, it costs less for the state to partially fund a child’s private school tuition than fully fund their education at a public school. During the first two years of the program, Indiana actually saved money with the program.

Fast-forward to this year: according to the Department of Education’s updated school choice report released in June, $40 million from the school funding formula is going toward vouchers. That’s because the eligibility requirements have changed. Families that weren’t eligible at the launch of the program four years ago now qualify for substantial subsidies.

During a speech on C-SPAN after the voucher law passed the Indiana General Assembly in 2011, former Gov. Mitch Daniels explained the purpose of the program was to include public schools into the school choice program.

“The family will only be eligible if the child has spent at least two semesters in a public school,” Daniels said.

The original law mandated families try public schools before getting a voucher for private school.

“In other words, if the public school delivers and succeeds, no one will seek, will exercise this choice,” Daniels said.

What came first? The voucher or the private school student?

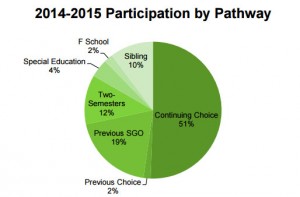

In the four years since Daniels delivered that speech, qualifying for a voucher has changed dramatically. If a student gets a voucher one year, they’ll get it again the next year. If the child has a sibling who gets a voucher, they automatically get one too. And if they received a scholarship from a state approved scholarship fund, which currently are all school choice advocacy groups, you get a voucher.

Expanding how a student gets a voucher means more middle income families are joining the program. According to the IDOE’s report, half of the students receiving vouchers never attended a public school.

More and more students using school vouchers are not from failing schools. (Photo Credit: Indiana Department of Education)

Steve Hinnefeld, an state education policy analyst, says this has changed the original intention of the law.

“The big debate really is whether students who are receiving vouchers who have never attended public schools, whether they would have attended public schools if it weren’t for the voucher or if their parents always intended to send them to private schools, figured they’d find a way to pay for it and now here’s a voucher so they’re doing it,” Hinnefeld says.

That exact scenario is playing out across the state. Half of the students are enrolled using voucher dollars at Community Baptist Christian School in South Bend, one of the cities using the most vouchers.

“A lot of them were already here but they qualified for vouchers so they went on the voucher program,” says Matt Fenton, Community Baptist Christian school administrator. “Over time as we’ve advertised on the website, we’ve said we’re a voucher school and other families have been able to take advantage of that.”

That means the state isn’t saving money because these students would have never used state money for education.

Timmerman says the governor’s office plans to continue funding the voucher program even if the rapid enrollment growth doesn’t stop.