After A Failing School Receives An “A”, How Do They Stay On Top?

First grade teacher Lindsey Heisler works with students at the Evans School in Evansville, IN. (Peter Balonon-Rosen/StateImpact)

Four years ago, test scores at the Evans School, in Evansville were low. So low, the elementary school qualified for a three-year federal grant for almost $6 million.

In the grant’s final year, something big happened. Evans catapulted from an F to an A in the state’s ranking system. Current principal Helene Blum was with students when she found out.

“So I very calmly tried to finish with them and then as soon as they left, went to the assistant principal and just screamed,” she said. “Literally, just screamed and to say we’re an A.”

But then a new reality set in.

“After a turnaround new challenges begin,” Blum says. “Now, it’s sustainability.”

- Working To Stay On TopAfter earning failing grades many years in a row, the Evans School in Evansville received federal money to help improve its academic performance. The money helped them earn an A grade, but now the school is trying to figure out how to maintain the improvement without the money that got it there.Download

So what did the $6 million dollar grant pay for? Largely, people. More teachers per grade. A social worker. An after school program, books and software.

Now that they aren’t a failing school they no longer receive that money, but they are trying to maintain the same programs.

“It’s a lot of looking at how can we achieve the same thing without the money to pay for it,” Blum says. “It’s a lot of creativity.”

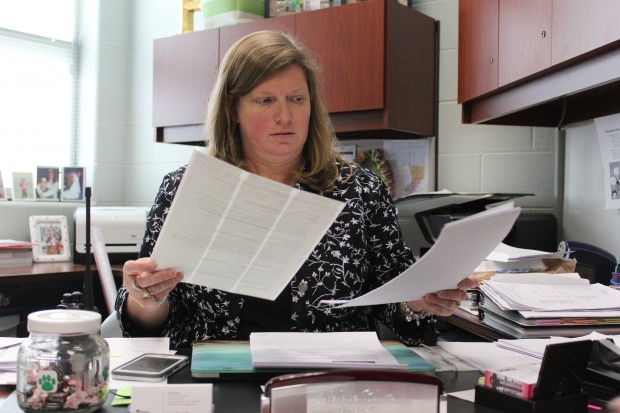

Principal Helene Blum at the Evans School. (Peter Balonon-Rosen/StateImpact)

One program they want to continue helps students focus on skills they are struggling to learn. Students are split into small groups based on how they score on a test the school gives every few weeks.

First grade teacher Lindsey Heisler says it’s a practice that helped the school achieve A status.

“And we pick the standard we really need them to excel at,” Heisler says.

But today, they have eight fewer teachers to manage it. And that personnel loss threatens many new programs and attempts to ensure all students feel like they have at least one staff member to turn to.

At Evans, nine out of every 10 students qualify for free or reduced lunch, a common indicator of poverty. Principal Blum says some students come to school with challenges from outside the classroom – histories of homelessness, trauma, violence.

And the social worker the grant provided was also laid off.

“You know the next piece to really maintain is to also make sure that we’re not only meeting the kid’s academic needs, but also the social emotional needs,” Blum says.

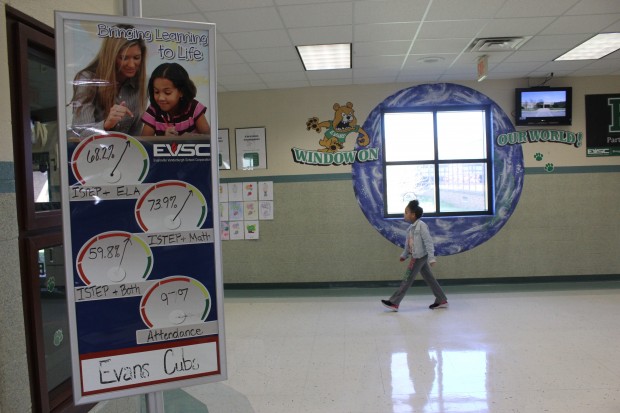

At the Evans School, test scores are publicly displayed. (Peter Balonon-Rosen/StateImpact)

To start, the school looked beyond it’s walls to find help.

After 6 months, Evans secured grants to help pay for a social worker. It also partners with AARP to get senior tutor volunteers to get extra hands on deck.

And there have been more challenges. This year, after layoffs, teachers and staff voluntarily resigned from 18 of remaining positions. Principal Blum says the long hours and hard work that come with working at Evans are “not the best fit” for everyone, but the positions have been filled.

For now, Evans still has an A in the state’s ranking system.

But test scores have been up and down. Last year, about 20 percent fewer students passed state English and Math tests. This was typical for schools across Indiana due to a new standardized test, so the lower scores were not counted against their current grade.

Fourth grade math teacher Larysa Euteneur helps students with an exercise at Evans School. (Peter Balonon-Rosen/StateImpact)

This is fourth grade teacher Larysa Euteneur’s first teaching job. She says teaching at the Evans School has been challenging, but worth it.

“I don’t feel like if I had gone to another school that was not a failing school that I would have learned nearly as much just because we’ve had to work from the ground up,” Euteneur says.

And they are now working to recreate some of those things.

“Well now I have one less person at my side to help with some of the grading and small groups and all of that,” Euteneur says. “The things we did at that time we’re still trying to keep up with.”

One of those things is coming in early to work on curriculum and get training from other teachers or district coaches.

Principal Helene Blum and Director of School Transformation Kelsey Wright hi-five during one of Wright’s weekly check-ins. (Peter Balonon-Rosen/StateImpact)

The district helps in other ways too. Evans is one of five district schools in what they call a transformation zone. Director of school transformation Kelsey Wright helps these schools set goals and meet them.

She says each week she checks in, pores over data and helps staff tweak things.

“I’m looking for sustainability,” Wright says. “If a school is able to fully function and maintain high student performance on their own, my work is done.”