Five Years Later, Indiana’s Voucher Program Functions Very Differently

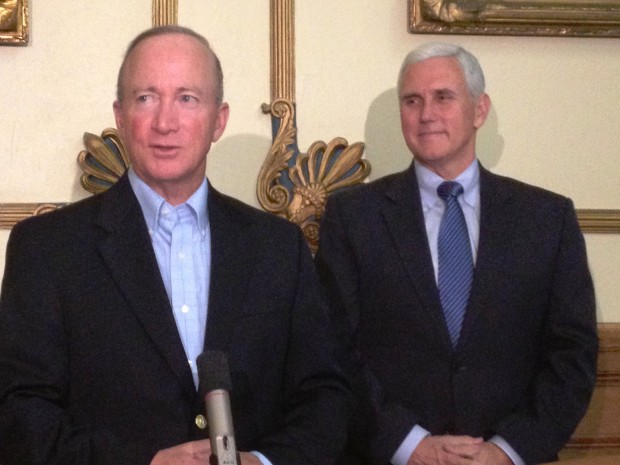

Former governor Mitch Daniels (left) oversaw the creation of the state\’s voucher program. Under the program passed in 2011, students from low income families could receive a voucher and only if they attended a public school for two semesters. Governor Mike Pence advocated for an expansion of the program in 2013, and the General Assembly listened; nowadays, there are seven ways a student can qualify for a voucher and it\’s available to middle and upper middle class families. (photo credit: Brandon Smith/Indiana Public Broadcasting).

It’s been five years since Indiana launched its school voucher program, which gives state money to to qualified students to cover private education. It was controversial when passed, and five years later, enrollment has grown exponentially, continuing the criticism.

Since Gov. Mike Pence joined the presidential race as Donald Trump’s running mate, the voucher program in Indiana is now in the national spotlight.

- Five Years Later, Indiana's Voucher Program Has Changed DramaticallyThe 2011 General Assembly put the state’s voucher program into effect, but five years later the program evolved into something very different from its original form.Download

The program has also reached an interesting political point. Former Gov. Mitch Daniels signed the program into law, and it expanded under Pence. Hoosiers will elect a new governor in November, and we don’t know yet how either candidate will address the program.

We wanted to take a look at how the program has evolved and how its outcomes look different than when it started five years ago.

The Birth Of Indiana’s Voucher Program

Back in 2011, former Republican Gov. Mitch Daniels saw the passage of the voucher program as a huge victory.

“Social justice has come to Indiana education,” Daniels said at the closing of the 2011 session.

It was the year of huge education reforms in Indiana: the legislature created the state’s A-F system, teacher evaluations were now required and based on student performance, and the voucher program was born.

The program passed in 2011 was based on the classic view of school choice supporters: all students should have access to all educational opportunities – money should not be a barrier.

And back then, a low-income student could get a voucher in two ways: one, if they were already receiving some sort of scholarship from an approved private organization. Two, if they attended a public school for one full school year and wanted to transfer.

In that first year, 7,500 vouchers were available.

“If they tried the public school and believe they are not serving their child well, they will not be forced to continue in those schools just because they don’t have a high enough income,” Daniels said.

And this was controversial from the start because of money. In Indiana public schools, the money follows the student. So if a lot of students use vouchers and go to private schools, the public schools lose money from that child.

Back in 2011, Daniels spoke to a conservative think tank a few months after he signed the program into law. At that speech, he said he didn’t expect this to become a big problem.

“It is not likely to be a very large phenomenon in Indiana,” he said “I think it will be exercised by a meaningful but not an enormous number of our students.”

The Program Expands Under Pence, Enrolling Tens of Thousands Of Students

Five years later, the program enrolls around 3 percent of the student population. Rep. Bob Behning, R-Indianapolis, wrote part of the founding school voucher legislation.

“I guess I look at 33,000 out of 1.1 million students, that’s still a very small percentage in terms of overall choice,” he said.

Critics say this can still hurt districts. For example, 4,500 students living in the Fort Wayne Community School district went to private schools last year.

Once Gov. Mike Pence took office in 2013, the program experienced a dramatic change, putting enrollment in the tens of thousands. In his first State of the State address after being elected, Pence praised the program and encouraged the legislature to expand it.

“Indiana has given parents who previously had few choices the ability to choose the public or private school that best meets the needs of their family,” Pence said.

Three major changes came out of this expansion in 2013.

The first was the financial requirement to get a voucher changed. When the program was first past, a student could receive a voucher if their family income was at 100% of the free-reduced lunch eligibility, around $45,000 a year for a family of four. These students got 90 percent of their private school tuition paid with a voucher.

After the 2013 legislation, the state was now offering a 50 percent scholarship to students from more middle and upper middle class families. The new income requirements now allowed families at the 150 and 200 percent FRL level ($67,000 and $90,000 a year for a family of four, respectively) to get half of their private school tuition paid by the state.

The second major change in 2013 was to the ways a student qualified for a voucher. Previously, a student had to go to a public school for a year or received a scholarship from a specific organization.

Now, they could get a voucher if an older sibling received one, if their assigned public school received an “F” on the state’s accountability system, if they were a special education student or previously received a voucher.

And the third change was the legislature said there was no limit as to how many vouchers the state could give out. If a student qualified, they received the money.

Questions Around The Financial Impact Of Indiana’s Vouchers

Molly Stewart is a research associate at Indiana University’s Center for Evaluation and Education Policy, and has spent more than a year preparing a report on voucher programs across the United States.

“Mainly we are looking at where is the source of voucher money and where is it going to?” Stewart said.

She questions the money middle class families receive under the 50 percent voucher. She says it’s possible that some of these families would have sent their kids to private schools regardless. But now they qualify for vouchers, so the state is paying for it.

“That to me is money the state is now spending on private education that it was not previously spending on public education,” Stewart said.

A report on the program released by the Department of Education shows the program costs $54 million. But Behning says the program saves the state money overall. Here’s his reasoning: when a child goes to private school, the state covers half or 90 percent of the tuition- depending on the family’s income.

But when the child goes to public school, the state covers instruction costs plus transportation, construction and infrastructure costs.

“There’s no way you can say it won’t cost more,” he said.

Which is true, less money is allocated to a voucher student than a public school student. But Stewart says it’s more complicated.

“If the idea behind a voucher program is we’re going to have the money follow the student, if the student didn’t start in a public school, the money isn’t following them from a public school, it’s just appearing from another budget,” Stewart said. “And we’re not exactly sure where that’s coming from.”

The one thing data does support – enrollment in the program is leveling off. Everyone says this is because available space from private schools is dwindling.