How Indiana Tracks Down And Educates Migrant Children And Workers

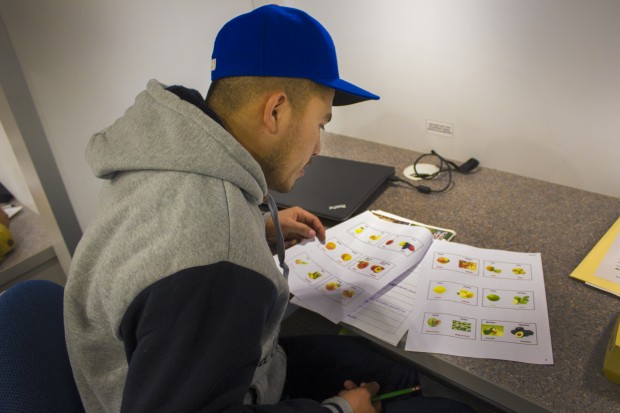

A student studies a sheet with fruits and vegetables in the Indiana Region 4 migrant education center’s mobile classroom. (Peter Balonon-Rosen/Indiana Public Broadcasting)

Alex Rodriguez dials an unfamiliar number on his cell phone.

“Yes?,” a voice on the other end answers. On speakerphone, the phone booms inside Rodriguez’s parked silver Ford Escape.

“This is Alex,” Rodriguez says. “I’m on the way to your home so that I can complete the enrollment for the kids.”

An estimated 3 million migrant workers travel the nation each year, following work. Depending on the season, Indiana farms employ between 2,000 and 20,000. And like anyone in the nation under 22, migrant workers and children are entitled by law to an education.

And that’s where Rodriguez comes in. He serves Indiana’s southwest region as one of Indiana’s six migrant education recruiters. His mission is simple: Find, recruit and enroll migrant children and workers for public school services.

- Despite The Odds, Indiana Teaches Migrant Children And WorkersAnyone under 22 qualifies for the Indiana’s migrant education program if they or their family has moved for seasonal field or farmwork, regardless of citizenship.Download

Today he sets out from a Wal-Mart parking lot in Vincennes. It’s the closest thing he has to an office.

He often parks here and finds prospective students. After all, he says, everyone comes to Wal-Mart.

“Just a minute ago, there was a bus full of migrant workers from Mexico,” Rodriguez says with a laugh, as he pulls away. “I didn’t know they were here.”

The Indiana Department of Education runs a program specifically aimed at educating migrant workers and children. It operates across the state. Anyone under 22 qualifies for the public service if they or their family has moved for seasonal field or farmwork. Regardless of citizenship.

“If it’s a youth 18 or older, maybe by themselves or a group of them, I usually think about English classes and some vocational programs that we have,” Rodriguez says. “If it’s a family I think about the program for the kids.”

To actually enroll children means tracking people down.

Julie Delosantos listens as Alex Rodriguez asks questions to fill out paperwork for the Indiana Migrant Education program. (Peter Balonon-Rosen/Indiana Public Broadcasting)

Inside the house Julie Delosantos rents, Rodriguez organizes his paperwork. For three years, the Delosantos family has moved from Texas to Indiana, following work.

“Do I need to fill out something for the baby?” Delosantos asks.

Delosantos has three children. Bella, her 1-year-old, is in Indiana for the first time.

“First move?” Rodriguez asks.

“For her,” Delosantos replies.

Rodriguez is here to sign up Bella for preschool and offer help to enroll the older children in local schools.

He verifies the family’s information, moving fluidly between English and Spanish.

“When you moved to work with the watermelons did you have specific [work] in mind?” Rodriguez asks.

He jots down the family’s responses with a blue pen and gets Delosantos’ signature.

“I have some books for you,” Rodriguez says. “It’s important for the parents to be reading to the kids so they can start getting to know what the books are.”

He hands over three books – items hard for migrant workers to travel with.

And then it’s back on the road.

Alex Rodriguez, left, holds an informal meeting in a Wal-Mart parking lot with Debbie Gries, education coordinator for the Indiana Migrant Regional Center. (Peter Balonon-Rosen/Indiana Public Broadcasting)

It’s not just workers’ children Rodriguez enrolls in school – it’s workers themselves, too. That means heading to the workers’ camps near local farms in Oaktown, Indiana.

The current political climate, however, makes things tricky.

“I might have cases that workers coming directly from Mexico not wanting to talk to me because they were instructed not to talk to any government people,” Rodriguez says.

Rodriguez wins trust, though. On any given day he brings food and clothes to workers and families. He helps people get medical attention.

“This is not part of my job,” Rodriguez says. “But it’s part of the services that can be provided to the migrant families.”

And it pays off.

Sitting next to the worker camp for Melon Acres farm in Oaktown, an RV gleams in the early evening sun. It’s owned by the Indiana Department of Education and now serves as a mobile classroom for the migrant education program.

As Rodriguez steps inside, he’s immediately welcomed with a surge of greetings.

“Hola!” students say. “Hola, profe!”

Young men, clad in dusty coats and weathered hats, gather in the classroom after a long day in the fields. They hunch over assessments to determine which class they will be in.

The first thing many want to learn? The English names of the crops they pick.

Pablo Cervantes Diaz is one such students. He came to the U.S. from Mexico on a temporary work visa. Just like his father did.

And then, here on this farm, he saw his father again – for the first time in 15 years.

Diaz says he’s grateful for this school program, one of six migrant programs in Indiana. He hopes it will lead to better opportunities for him and his future family.