Across Indiana, University Faculty And Staff Reel From Trump’s Immigration Order

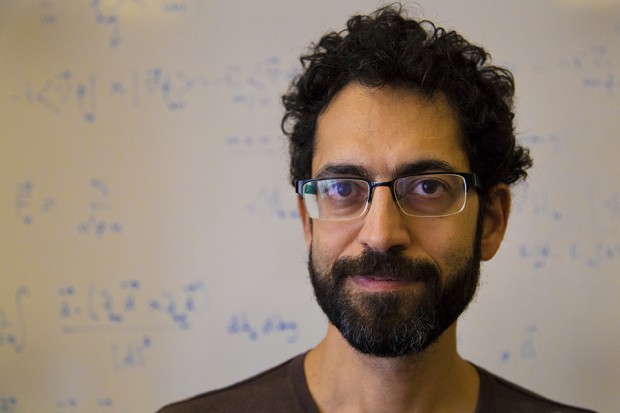

Babak Seradjeh is an associate professor of physics at Indiana University. (Peter Balonon-Rosen/Indiana Public Broadcasting)

For Babak Seradjeh, it’s routine by now — as a celebrated physicist at Indiana University, he travels abroad three or four times a year for work. Last Saturday, the associate professor, with dual Iranian-Canadian citizenship, was heading to Israel.

“I left my house at 8:30, I took a shuttle to the airport,” Seradjeh says.

But as Seradjeh departed, little did he know he’d be one of the thousands worldwide affected by a new travel ban, implemented by President Donald Trump. The night prior, Trump signed an executive order that blocked citizens of seven countries, refugees or otherwise, from entering the United States for 90 days: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

“I thought this is not going to apply to me,” Seradjeh says. “I can still take my trip. And that’s why I started my trip.”

But it did apply to him. And soon Seradjeh became one of about 100 Indiana University faculty and staff affected by the order banning travel into the United States.

- University Faculty And Staff Feel The Effects Of The Temporary Immigration And Travel BanAs universities officially condemn the order, their employees are restricted by it.Download

Seradjeh, a legal permanent U.S. resident with Iranian citizenship, was at the airport, heading out of the country.

“I checked with the airline representatives there and they said they had some memo that permanent residents were not affected so I checked in,” Seradjeh says.

The order also suspended all refugee admissions for 90 days and indefinitely barred Syrian refugees.

But when the connection landed in Newark, Seradjeh checked the news. He saw reports that dual-nationals – from the seven countries – could also be barred from returning to the U.S. People just like Seradjeh.

“So basically, everything that I thought would protect my return home was gone at that point,” Seradjeh says.

With no guarantee of return, he turned around, put the research on hold, and went home to his family and the associate professor job he’s held for six years.

“It felt like the ground was shifting under my feet, just being in a mudslide or something like that,” Seradjeh says. “This happened like overnight almost, with such sweeping effect. Whenever I’m going to take another trip I would be concerned if that can happen again.”

He’s not alone. Faculty and staff across the Indiana University system have cancelled professional and personal travel.

Chris Viers is with Indiana University international services. He says his phone has been ringing off the hook with students, faculty and staff looking for answers.

“It, uh, was non-stop… but our commitment here at IU is to do absolutely everything that we can to proactively communicate what’s happening,” Viers says.

For both professors in and out of the country.

“An individual that I just spoke with recently is outside of the U.S. He has a German passport, but is originally from Iran, and he’s wondering if he will be impacted by the ban and it’s just not quite clear yet,” Viers says.

While people wait for clarification, the university is offering services to help affected faculty, staff and students deal with stress and anxiety – including information sessions on all IU campuses.

Across the university about 150 students, about 100 faculty and staff and 160 prospective students are impacted. He says they’re not a threat to national security.

“Educational exchanges are one of our country’s most successful foreign policy tools,” Viers says.

He says they combat stereotypes, both at home and aboard. But for now he’s asking people from those seven countries to stay put.

Just because of the uncertainty as to whether or not they will be able to return.

Even as the presidents of universities including IU, Purdue and Notre Dame are condemning the order, faculty like Seradjeh are playing it safe.

In his office, traces of chalk dust linger on a brown shirt. Seradjeh’s just finished teaching for the day. He clicks through photos of a past trip.

Seradjeh pulls up a photo of a white board, covered in math equations.

“This is a board with our work on it and this turned into a paper,” Seradjeh says. “This is in my office there in Ben-Gurion University.”

And seeing the photos leaves Seradjeh with a bittersweet feeling.

“It feels like I want to be there,” Serdjeh says.

He’s waiting to see what comes next.