Five Questions Parents Should Ask When A District Goes One-To-One

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

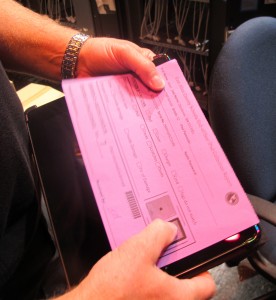

East Allen County Schools technology director Bill Diehl holds a checklist used to make sure students return their iPad, cover and charger in good condition.

“I wish I could give every parent the same tour I just gave you,” East Allen County Schools technology director Bill Diehl told me as I packed up my recording equipment last month.

I was in northeast Indiana working on a story about technology initiatives, and Diehl had just finished walking me through the logistics of overseeing a large-scale one-to-one program. We were in the room where the district’s 7,000 student iPads are being stored for the summer.

“If they knew that this is what’s going to be carried around,” says Diehl, holding up his iPad, “you can still take paper and pencil notes if you want, but I could show you all the cool programs we have on them to take notes.”

Of course, Diehl doesn’t have time to explain to every parent how the district is using technology in the classroom. What he can do is host iPad informational meetings and make presentations before the school board.

Still, not all parents are sold, he says.

Getting parents on board is an important part of any one-to-one technology initiative. In fact, Indiana University professor Krista Glazewski told us the most successful programs are typically those that take into consideration the concerns of teachers, students and parents.

“Where one-to-one programs have the most impact are when schools are making building-level decisions about how to use the devices, so the models look very different from school to school,” she says. “That’s a good thing because parents can have a voice in what it looks like.”

We asked Diehl, Glazewski and Buffton-Harrison technology director Scott Ribich for tips on how parents can navigate the new world of education technology.- What is the acceptable use policy? “Every district will have that in place and will be communicating that to parents for sure,” says Glazewski. But policies can vary widely across districts, so it’s important to know exactly what your school expects. For example, some schools bar all access to social media, while others only lock down access to Facebook and Twitter during class time. Bluffton-Harrison recommends parents reinforce the acceptable use policy at home by talking to their kids about digital citizenship. And if your child brought home a device last year, be sure to ask if the policy has changed — schools often make tweaks once they figure out what works.

- What happens if my student does break the rules? East Allen County treats any violation of the acceptable use policy as a discipline problem. District technology staff can “lock” an iPad if a student is playing games in class or otherwise breaking the rules. “Boy was there whining all over the district when the kids found out that we could restrict their iPads, turn off all their apps, turn off all their music, turn off their camera and all the fun things,” says Diehl. If an iPad does have to be locked down, Diehl says students are given a date when they can have it turned back “on” by the librarian.

- Do I have to attach a credit card to my kid’s device? Students need an Apple ID to download anything — even free, educational tools — from the App Store to their iPad. Students are prompted to enter a credit card number when they sign up. “There are all these kind of nightmare stories about kids using devices and then using applications that require pay-for-purchase,” says Glazewski. But a credit card isn’t required to create an Apple ID. If giving your kid access to your account makes you nervous, skip this step and use iTunes gift cards when it’s time to buy required electronic textbooks. Since apps are linked to an Apple ID, make sure your student is following district guidelines on periodic device back up.

- Who pays if the device breaks? In most cases, it’s the student. Many schools offer families some type of insurance policy, but what’s covered varies. East Allen County offers an optional policy for $30. It lowers the price of a missing device from $499 or $599 (depend on the size) to $100. But it won’t help families pay for a cracked screen, which costs $100 to fix. If your district provides a protective case, talk to your student about keeping their school-owned device in it at all times. Ribich says he sees students using their iPads without the cases all the time, leaving them less protected from drops and spills.

- How will my kid do homework if his device breaks? No parent wants to think about shelling out for a new iPad or netbook, but it’s important to know the district policy on loaner devices if an accident does happen. “If at any point, a student breaks an iPad, we’ve got to get him or her a replacement because that’s what our textbooks are on,” says Ribich. “For a student to be without an iPad for a day or so is just not acceptable here.” But not every school will provide a loaner if the student’s iPad is out for repair. Diehl says East Allen County students who are without a device for several days are told to work with a friend or classmate.

Teachers and technology directors (and parents whose kids brought home one-to-one devices last year), what other questions should parents ask?