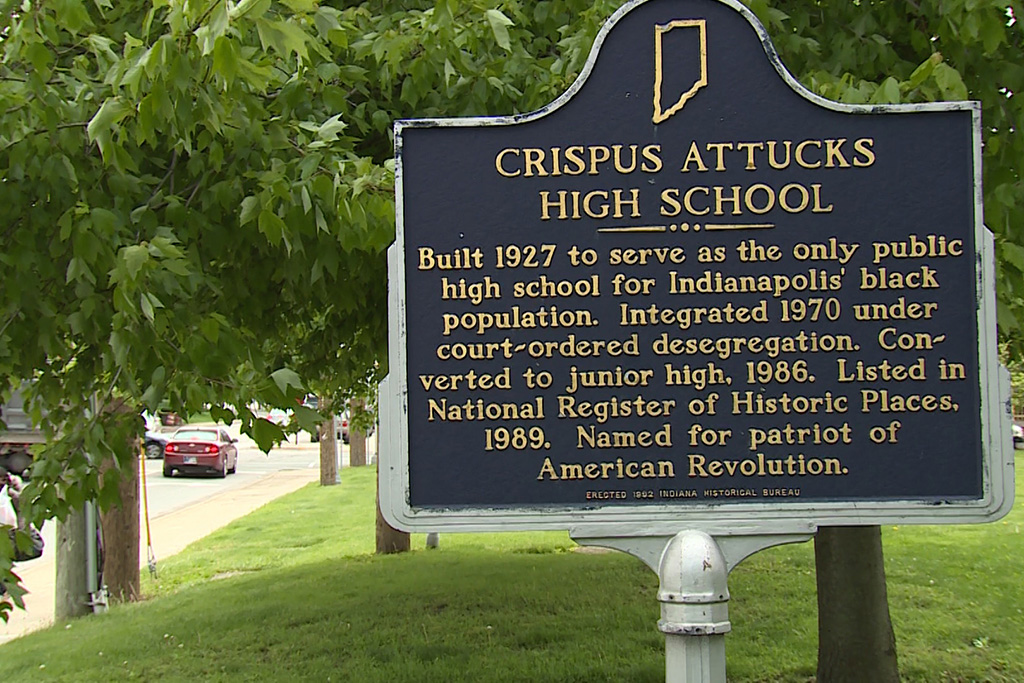

Crispus Attucks High School was created because of the demands of segregationists in the 1920s. It was the first and only all-black high school in Indianapolis. (WFIU/WTIU News)

Noon Edition airs on Fridays at noon on WFIU.

Recently, Shelby Hoshaw asked a question through our City Limits project about the history of racism in Indiana.

“And, it’s an important part of our history and we shouldn’t be afraid to talk about it,” she says. “Because without talking about it, we’re not going to address the issues that are happening today.”

IU historian James Madison told WFIU reporter Barbara Brosher that the history of racism in Indiana predates the state’s founding.

Evidence of these attitudes are exhibited in the first state Constitution in 1816. It says slavery is illegal, but forbade black men from voting.

During the height of the KKK’s power in the 1920s, it heavily influenced the state politically. In 1924, Edward Jackson was elected governor. He was rumored to be a Klan member because of his ties with an Indiana Klan leader.

Crispus Attucks, the first and only all-black high school in Indianapolis, was opened in the same decade.

It was built to keep white and black students from attending school together, and then became a point of unity in the black community.

Later, in the 1970s, Indianapolis city officials joined the Marion County and Indianapolis governments, but this did not unify the school systems.

There are indications that these attitudes are improving.

Last year the KKK held a rally in Madison, Ind. But people protesting the event far outnumbered the event’s attendees.

Madison says it is up to Hoosiers to make a change and stand up against prejudice.

Join us this week as we talk about how Indiana’s history of racism affects our present and future.

Our guests:

James Madison, Professor Emeritus in Indiana University’s History Department

Clarence Boone, Former Associate Director of Communities and Diversity Programs at Indiana University Alumni Association

Jim Sims, City Council At-Large and former Monroe County NAACP President

Pamela Jackson, Professor in Indiana University's Department of Sociology, Bloomington Human Rights Commission member

Join our discussion by tweeting your questions @noonedition or calling (812) 855-0811 or toll-free at 1-877-285-9348.

Conversation

Boone says Indiana used to have sundown towns, which he says are towns where black people could pass through, but once the sun was down, it was expected that they were gone. This was upheld through rules or forms of intimidation. He says that the KKK had a stronghold in Indiana.

“Those things leave an impression and if that’s in the DNA of your state, that lingers a long time, and it’s reflected in policies, housing, education, just getting involved in government, or just the right to send you kids where you want them to go to college. Those things have a permanency unless they’re addressed,” Boone says.

Madison says that to move forward, it is important to discuss the complexities racism and its historical roots. He mentions Indiana’s first Constitution and the discrimination that it wrote into law. He says that prejudice persists today, and feels that the state has moved backwards in recent years, referencing national political events.

“Maybe we’ve made some improvements in one sense, but other places have moved forward much better than Indiana. There’s all sorts of evidence for that, like the failure to pass the anti-hate bill this past session in the General Assembly. The composition of Indiana’s General Assembly, there are very few black faces in that body. They’re all old, white men, and speaking as an old white man with white privilege, there’s things I don’t understand. We need in that General Assembly people to represent the state of Indiana that really do represent that state of Indiana," he says.

Jackson teaches ‘Racism as a Social Problem’ sociology classes at IU. She disagrees that people’s attitudes have moved backwards. Rather, she says recent political events have given people with closeted racist and prejudice views a platform. She references Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail;

“…he describes for the audience a group of people who were ambivalent about race relations, and he talked about the danger of that group of people, the fact that they are the problem because they are not outraged enough about racism. So what I am imagining happening is just a reveal of those individuals who have never taken a strong stand one way or another, but have in this hour felt empowered to take a different kind of stand. I imagine there are simply people who have been closet racists, and they now have a platform and opportunity to express those feelings,” she says.

Sims says many people have the wrong impression of Bloomington being an “oasis” for minority communities. He points out that in Bloomington’s 200 year history, he is only the second African American to serve on the Bloomington City Council.

“This phrase was coined by Rep. Crawford, an African American state legislature, and one of the things he would always say is, ‘we want a seat at the table.’ That was like a mantra for a while. We have progressed past that. One of the things I say is not only do we want a seat at the table, we want the power that comes with that seat. That means the folks that have the power, that have the privilege must be willing to seed some of that,” Sims says.