From "The Sidewinder" to A Love Supreme, from the titanic impact of the Beatles to the long-lasting influence of a small avant-garde festival in New York City, and much more, 1964 proved to be an eventful year in the world of jazz. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear the music of Lee Morgan and Miles Davis, Horace Silver and Eric Dolphy, Albert Ayler and Mary Lou Williams, and other artists who made notable records in that span of 12 months.

A Swirl Of Past, Present, And Future Currents

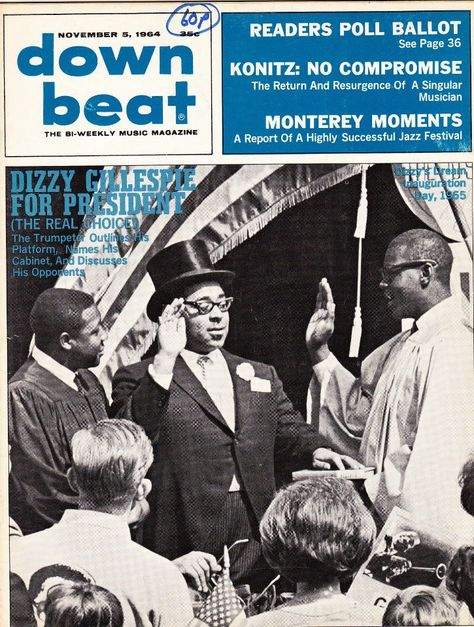

1964. The Beatles were coming, revolution was in the air, and Blue Note Records was at its apex. Pianist and composer Thelonious Monk appeared on the cover of Time Magazine, a story that had originally been slated to run in late November the year before, rescheduled because of the assassination that week of U.S. president John F. Kennedy. Kennedy‘s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, campaigned for re-election against Arizona Republican Barry Goldwater, while an unexpected challenger for the office came from the world of jazz in the person of trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, who proposed renaming the White House "the Blues House." Gillespie also envisioned aa presidential cabinet that would include Duke Ellington as minister of state, Max Roach as minister of defense, Charles Mingus as minister of peace, Peggy Lee as minister of labor, and Miles Davis as director of the CIA.

The Sixties were beginning to brew, and 1964 would yield a diverse set of jazz releases that reflected a swirl of past, present, and future currents. In an era when jazz records still sometimes became hits, two mainstream jazz artists scored big in 1964. Saxophonist Stan Getz continued his bossa-nova run with "The Girl From Ipanema," while trumpeter Lee Morgan, who had been laying low for the past couple of years, returned with a bang, a hardbop boogaloo that overwhelmed Morgan‘s label, Blue Note Records, with consumer and vendor demand:

Dizzy Gillespie‘s 1964 campaign for president was ultimately unsuccessful (though another jazz musician, Dave Brubeck, got to perform at the White House that year), so he never had the opportunity to offer Miles Davis the job of running the CIA. Miles, in the meantime, was putting together the best group he‘d had since the Kind Of Blue era of the late 1950s, with a dynamic young rhythm section of pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Tony Williams. Wayne Shorter would join later, but at the start of the year George Coleman was more than adequately holding down the tenor sax chair. In February Davis performed at a civil-rights benefit in New York City—a convergence of music and cause that was occurring more and more frequently in the jazz world. Davis‘ band, however, was less than happy when he announced that he was waiving his group‘s fee, and he later wrote that "I think that anger created a fire, a tension that got into everybody‘s playing."

Wayne Shorter would eventually take over the tenor sax chair in Miles' 1964 group, completing what would come to be known as Davis‘ "Second Great Quintet." Hardbop pianist and composer Horace Silver also reconfigured his group in 1964, after having worked with the same musicians for nearly five years, bringing aboard tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson and trumpeter Carmell Jones, as well as bassist Teddy Smith and drummer Roger Humphries. Inspired by the popular bossa-nova sound and childhood memories of his father and others performing music at parties, Silver wrote a tune that became another hit for the Blue Note label:

The British Invasion: Jazz Hits Back

When the Beatles landed on American shores and appeared on "The Ed Sullivan Show," setting off Beatlemania, the jazz world reacted for the most part with scorn and anxiety. But some old-guard artists quickly began to adapt Beatles songs into their repertoire, one of the first being Ella Fitzgerald, who scored a hit in England with her version of Lennon and McCartney‘s "Can‘t Buy Me Love." Ironically, the Beatles‘ original recording of that song was knocked off the top of the charts in America that spring by none other than Louis Armstrong, a self-proclaimed Beatles fan who scored a late-period smash with his version of the Broadway tune "Hello Dolly":

Another jazz veteran whose roots went back to the swing era, Mary Lou Williams, extended her spiritual beliefs into a religious-themed album in 1964 called Black Christ Of The Andes, prceding Duke Ellington‘s efforts in this realm by a year. 1964 also saw the advent of Albert Ayler, an avant-garde saxophonist whose own spiritual beliefs found expression in his intense, broad vibrato sound that distilled gospel, marches, and New Orleans, and R & B roots into his own form of free jazz:

One figure who straddled the worlds of avant-garde and mainstream jazz passed away suddenly and unexpectedly in 1964. Multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy, a controversial addition to John Coltrane‘s 1961 group who‘d made an excellent run of albums under his own name for the Prestige label, died in Germany at the age of 36 after lapsing into a coma brought on by an undiagnosed diabetic condition. Earlier that year Dolphy recorded an album for Blue Note that many now consider to be his masterpiece, showcasing his wide-ranging and exploratory compositional and performing strengths. From Out To Lunch, here‘s Eric Dolphy‘s "Something Sweet, Something Tender":

Just three months after Dolphy‘s death that year at the age of 36, trumpeter Bill Dixon organized The October Revolution in Jazz, a festival to celebrate what was being called "The New Thing", an avant-garde movement that looked to the recent efforts of artists such as Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor for inspiration. Performers included Paul Bley, Sun Ra, and Roswell Rudd. The concerts took place over four nights in New York City‘s small Cellar Café, with panel discussions that included jazz critics and musicians, and led to the formation of the Jazz Composers Guild, a collective that aspired to greater creative and entrepreneurial control of musicians‘ work. While only some brief snippets of the festival are known to have been recorded, here‘s music from Bill Dixon‘s "Winter Song" that he recorded earlier in the year for the Savoy label, on Night Lights:

In the final month of 1964, saxophonist John Coltrane traveled to Rudy van Gelder‘s studio in New Jersey to record a multi-part composition he‘d written as summer turned into autumn; his wife Alice Coltrane later recalled that when he emerged from his work area after four or five days of creation, "It was like Moses coming down from the mountain, it was so beautiful. He walked down and there was that joy, that peace in his face, tranquility…. He said, ‘This is the first time that I have received all of the music for what I want to record, in a suite." The suite was A Love Supreme, a majestic album of extraordinary power and influence, and its landmark release would help usher in 1965:

More From 1964 On Night Lights

More Of The Year In Jazz