At the end of 1965 pianist McCoy Tyner left John Coltrane‘s group and struck out on his own, eventually recording a series of albums for the Blue Note label that began the extension of his jazz legacy beyond the Coltrane quartet. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear Tyner with musicians such as saxophonists Joe Henderson and Wayne Shorter, vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, and trumpeter Lee Morgan as we explore the pianist‘s career in the late 1960s.

In March of 1966, DownBeat Magazine reported that both drummer Elvin Jones and pianist McCoy Tyner had left saxophonist John Coltrane‘s group. Both men had played with Coltrane since the beginning of the 1960s, occupying key roles in what has come to be known as "the Classic Quartet." Tyner‘s percussive approach, often described as "oceanic" and rooted in modal fourth chords, was part of the signature sound of the group. But as Coltrane moved further into avant-garde explorations and added second bassists and drummers to the band, Tyner felt he could no longer relate to what his leader was doing. He also said that he couldn‘t even hear what he himself was doing at times. So the 27-year-old pianist set out to forge his own musical path.

Tyner initially played with clarinetist Tony Scott, saxophonist Sonny Rollins, and Art Blakey‘s Jazz Messengers, as well as leading his own trio. But the late 1960s would prove to be a difficult time for the pianist, who nearly turned to cab-driving at one point to make ends meet. "Who was it who said, ‘It takes pressure to create diamonds‘?" he said many years later about this period. "Sometimes you can only learn through adversity. If a man‘s faith isn‘t tested, I don‘t think he‘ll learn anything."

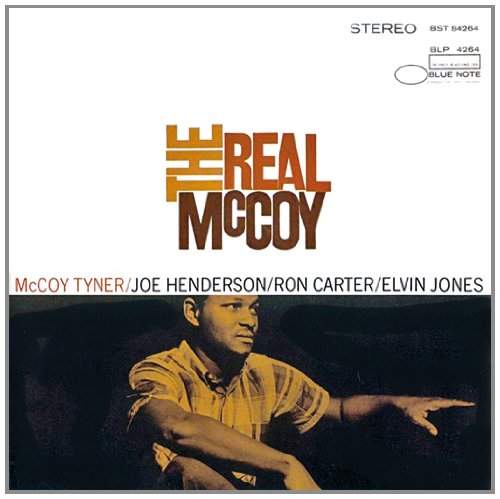

Tyner eventually began to record as a leader for the Blue Note label, where he‘d worked as a sideman since 1960, appearing on albums by Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, Grant Green, and many other notable Blue Note artists of the time. His debut, The Real McCoy, brought him together with former Coltrane bandmate Elvin Jones, as well as saxophonist Joe Henderson and bassist Ron Carter. It also gave Tyner a chance to showcase his own compositions, several of which have become jazz standards:

Looking back 40 years later, Tyner told DownBeat writer Bill Milkowski,

I think at the time I conceived the music for that album it was an important thing for me to make a personal statement. It was the first album I had done as a leader since leaving John‘s band… I learned so much from playing with him. He was like my teacher. And a lot of what I learned from him transferred to that recording. So I was sort of inspired when I wrote tunes like ‘Search For Peace‘ and ‘Passion Dance‘ and ‘Blues On The Corner.‘ Some songs, they sort of attach themselves to you, and these definitely did. I still play them.

Tyner followed up The Real McCoy with a greatly-expanded ensemble on Tender Moments, recorded at the end of 1967. Tyner said in the liner notes that he‘d been "doing some reading about orchestration," and the writing he did for the nine-piece Tender Moments sessions points the way towards the varied musical settings he would explore in the decades to come. Liner note writer Leonard Feather paraphrased Tyner‘s description of one composition, "Utopia," as "a reflection, through its intensities and dynamics, of the ups and downs of our lives, with high points and moments of quiescence." In retrospect that sounds like an apt accounting of Tyner‘s 1960s era as well:

Tyner often had trouble finding enough musical work to get by in the years following his departure from John Coltrane‘s group at the end of 1965. Those who saw the pianist's live performances in the late 1960s were effusive in their praise, but trumpeter Woody Shaw, who played and recorded with one of Tyner‘s working groups, said they jokingly referred to themselves as "the Starvation Band" because of their inability to get gigs. One Tyner fan complained in a 1970 letter to DownBeat when Tyner failed to make the pianists list for the International Critics Poll:

When will the critics wake up, listen, and give this man the credit he so truly deserves? Tyner has had a tremendous influence on many pianists on the contemporary scene. He is also an excellent composer and arranger.

In the meantime, Tyner continued to record for Blue Note, including a 1968 album date with the group featuring Woody Shaw, with saxophonist Wayne Shorter thrown into the mix as well. From Expansions, here‘s McCoy Tyner and "Peresina":

Tyner would go into the studio six more times in the next two years, but the results would not be released until the mid-1970s, and the hard economic times continued for the pianist, who was supporting a wife and children as well as himself. Some of the difficulty could be ascribed to the rapidly-changing musical landscape and marketplace of the late 1960s and early 70s that threatened to leave acoustically-based jazz artists like Tyner behind. "It was almost like we had gone to a certain point, it was time to take off and someone said,‘You guys have done enough now, let‘s move you in the back a little bit.‘" Tyner said in a 1983 interview. "I was one of the guys for whom it seemed to dry up pretty quickly." From his final recording session from this era for the Blue Note label, here‘s McCoy Tyner and "Goin‘ Home":

"Goin‘ Home" was recorded in 1970, but not released until 1974 as part of the album Asante. By then Tyner was ensconced at a new label, Milestone, where he would continue to expand his musical concept in both small-group and larger-ensemble settings, developing his unique post-Coltrane Quartet voice. Reflecting years later on the struggles he encountered after leaving John Coltrane‘s group, Tyner said,

It‘s funny, though; along with the pressure, it was one of the happiest times of my life. I didn‘t travel much; I became very close to my family. It renewed my faith in the Creator. Despite the adversity, this was a fulfilling period because it was a test of my ability to survive, personally and as an artist. I had a chance to compromise, and I didn‘t do it.

From Tyner‘s Blue Note album Extensions, on which he was joined by Coltrane‘s widow Alice playing harp, here‘s McCoy Tyner and "His Blessings":

For an outstanding deep dive into Tyner's 1960s era, check out this blog post from Ethan Iverson: