In 1963 John Coltrane was one of the most popular saxophonists in jazz, still riding a wave of success and recognition from his recording of the song "My Favorite Things." His group that would come to be called "the classic quartet," with pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones, had been working and recording together for the past year. Coltrane was also emerging from a period of controversy, in which he‘d been criticized by some jazz journalists for the adventurous turn his sound had taken, particularly in the company of multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy. He would later allude to dental problems and issues with his mouthpiece presenting challenges during this time as well.

"A New Room In The Great Pyramid"

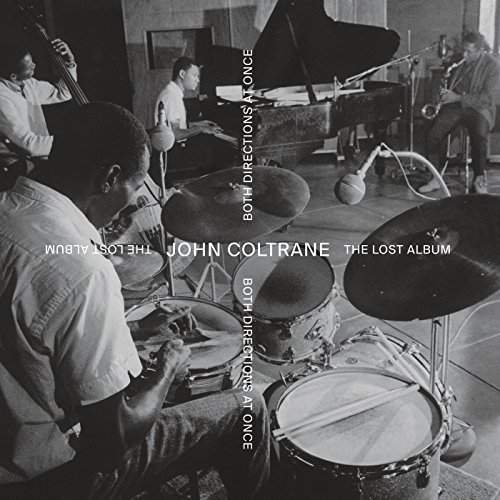

Coltrane was a musician in transition, never content to stand still artistically, and we are fortunate that both his studio and live performances were so extensively documented throughout the 1960s; even today previously-unheard recordings sometimes come to light. In 2018 a session comprising an album‘s worth of material from early 1963 surfaced, a development that Coltrane contemporary Sonny Rollins compared to "finding a new room in the Great Pyramid." Here‘s John Coltrane in March 1963, performing an original composition released 55 years later:

The following day the quartet returned to engineer Rudy van Gelder‘s New Jersey studio where they made their recordings for the Impulse label, but this time with singer Johnny Hartman in tow. The year before Coltrane had recorded a ballads album and collaborated with Duke Ellington on another LP, moves seen by some as a response to the hostile criticism he‘d received for his work with Eric Dolphy. When Impulse producer Bob Thiele proposed doing a date with a vocalist, Coltrane suggested Hartman, who was little-known outside the jazz world at the time. Hartman‘s deep-evening baritone proved an excellent match for the Coltrane quartet in ballad mode, and the result was an iconic jazz-vocal album-the only one that Coltrane ever made. What some consider to be the album‘s most memorable song wasn‘t even on the original recording list; Coltrane and Hartman heard Nat King Cole‘s recording of it on the radio while driving to the studio and decided at the last minute to add it.

Coping Without Elvin

It would be hard to overstate the importance of Elvin Jones in John Coltrane‘s early-1960s quartet. His fiery polyrhythmic approach and swirl of accents provided the group with an ongoing supply of inspiration and power. Coltrane biographer J.C. Thomas recounted his subject‘s response after hearing that Jones had wrecked a new car that his leader had loaned to him: "I can always get a new car," Coltrane said, "but there‘s only one Elvin." A few weeks after the session with Johnny Hartman, Jones had to leave the band for several months, spending late April through late July at the Lexington Narcotics Hospital in Kentucky. Coltrane called on Roy Haynes to take his place. Haynes‘ resume, in addition to his own dates as a leader, went back to the 1940s and included stints with Lester Young and Charlie Parker. Now he would help propel Coltrane‘s rhythm section and sustain the group‘s dynamic momentum across the late spring and summer of 1963:

Roy Haynes continued to fill in for Coltrane‘s regular drummer Elvin Jones throughout much of the summer that year--not an easy task, given the intricate chemistry of the quartet. Earlier that year Coltrane‘s former boss Miles Davis had sat in with the band at Birdland, with McCoy Tyner later commenting that it hadn‘t gone well:

There wasn't any room. He didn't quite work. We were very special. It was very difficult for anybody to walk up and come into the band.

But Haynes filled in admirably. "Roy Haynes is one of the best drummers I ever worked with," Coltrane said in 1966. "I always tried to get him when Elvin Jones wasn‘t able to make it. There‘s a difference between them. Elvin‘s feeling was a driving force. Roy‘s was more of a spreading, a permeating." Haynes was still the drummer when the Coltrane quartet appeared at the Newport Jazz Festival that summer:

A Life-Changing Encounter

Elvin Jones returned to the band near the end of July, and around that same time another significant event occurred in John Coltrane‘s life. While appearing opposite the Terry Gibbs Quartet at New York City‘s Birdland, he met Gibbs‘ pianist, Alice McLeod. Though Coltrane was married at the time, he had several conversations with Alice backstage that left each sensing a strong spiritual attraction between the two of them. "It was really like two friends that had known each other many, many years," she later recalled. "It was so beautiful." Coltrane told a colleague that "she has a strange kind of strength; it‘s not just sounds, it‘s like an aura. Sometimes you can feel it, even see it--more than you can hear it." Eventually she would have three children with Coltrane, marry him, and become the pianist in his band when McCoy Tyner left at the end of 1965.

That autumn Coltrane made a live recording at Birdland, and he also took the quartet to Europe. He was featuring a new addition to his repertoire, written by Cuban percussionist Mongo Santamaria. From a November 1963 Berlin performance, here‘s "Afro-Blue":

In an interview late that year Coltrane talked of taking some time to focus on writing new material:

I'm working on approaches to the problem of writing for a group. I've gotten enough solved to do a few things which I think might be up to the standard of what we've done so far... I'm going to let the nature of the songs determine just what I play... It might be modal, it might be chord progressions, or it might be just playing in tonal areas.

Those efforts would soon lead to the suite A Love Supreme, but a recent tragedy had already inspired Coltrane to record a new piece, a haunting, searing response to the white-supremacist bombing of a Birmingham, Alabama church in September 1963 that had killed four African-American girls. It sounded like the rumble before a storm. Here's Coltrane's live performance for the TV program "Jazz Casual" on December 7, 1963:

More Coltrane, More 1963 On Night Lights

Trane '62: The Classic Coltrane Quartet Begins

Trane '57: John Coltrane's Pivotal Year In Jazz

1963: A Man's Dream, A Nation's Nightmare

Also:

NPR's Nate Chinen reviews the "lost" 1963 John Coltrane album

A powerful, unreleased 1963 concert in Stuttgart, West Germany

On the last night of 1963, Coltrane's quartet, augmented by Eric Dolphy, appeared at Lincoln Center's Philharmonic Hall. The other acts on the bill that evening? The Cecil Taylor Jazz Unit, featuring Albert Ayler and Jimmy Lyons on saxophones, Henry Grimes on bass, and Sunny Murray on drums; and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, with a lineup that included Wayne Shorter on saxophone, Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Curtis Fuller on trombone, Cedar Walton on piano, and Reggie Workman on bass. Crank up the time machine and set it to December 31, 1963!