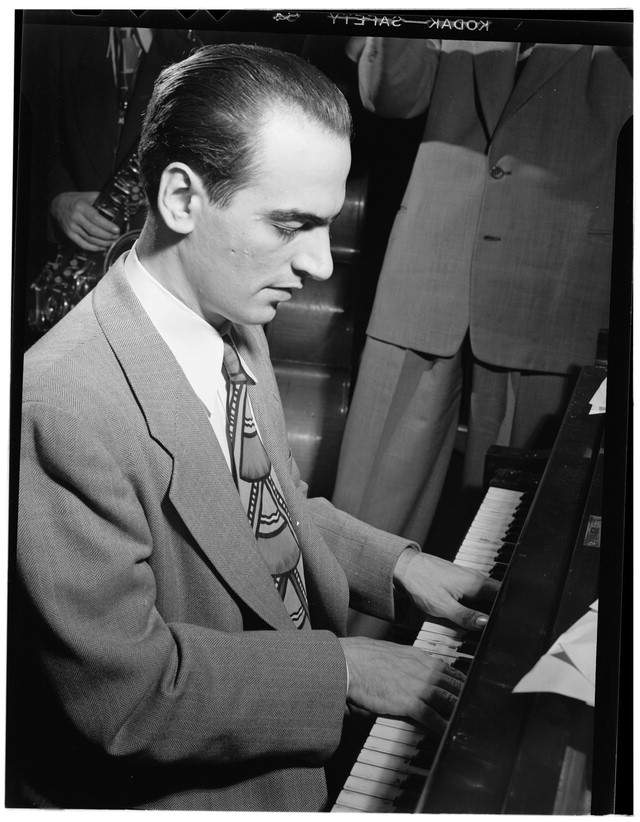

Pianist Lennie Tristano was a singular and charismatic modernist and mentor whose methods helped point the way for the rise of jazz education. Not known as a prolific performer when it came to either studio or live recording dates, Tristano nevertheless left behind an impressive and influential legacy of music. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear tracks often cited as the first free-jazz and overdubbed jazz recordings, an all-star date with Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Charlie Parker, and performances with Tristano‘s proteges, saxophonists Lee Konitz and Warne Marsh.

Lennie Tristano‘s influence as a pianist and jazz teacher is perhaps more felt than known, an undercurrent detected at times in the mid-1960s recordings of the Miles Davis Quintet, or the modern-day efforts of artists such as saxophonist Mark Turner and pianist Ethan Iverson. A figure of controversy both championed and scorned when he emerged on the jazz scene in the late 1940s, Tristano retreated from public performances in later years and made few commercial recordings, concentrating on giving private lessons at home to a large number of students that sometimes included established musicians. He has often been labeled "cool jazz" and "intellectual" or "cerebral," and his charismatic personality and strongly-held beliefs contributed to his reputation as a "jazz guru" of sorts, with a cult-like influence over his followers. Ironically, though, what Tristano sought, both for himself and his students, was the antithesis of such lables--an independent sound that was always in service of feeling.

Tristano was born in Chicago, Illinois on March 19, 1919. He took to music quite early and learned to play a variety of instruments, including clarinet and saxophone as well as piano, though he took only a handful of lessons. Born with deficient vision, by the age of 10 he was blind, but not long after began to play his first professional gigs. He attended a school for the blind through 1938, then studied at the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago until 1943. He became a habitue of the Chicago jazz scene and also began to teach in the early 1940s. His youth in Chicago was significant in several ways; he began to find his own sound, breaking free of the influence of pianist Art Tatum; he married a woman musician, Judy Moore; he crossed paths for the first time with a teenage saxophonist, Lee Konitz, who would become an important associate; and he began to attract attention in the jazz press. In 1946 he moved to New York City and made his first commercial recordings for the Keynote label. In his 1989 book The Swing Era, jazz scholar Gunther Schuller called Tristano‘s "I Can‘t Get Started"

one of the most prophetic recordings in all jazz history…the original song is the merest pretext for a whole new concept of jazz in which tonality and atonality, harmony and counterpoint, meet on common ground, in brand new fusions…Tristano‘s early work pulsates with the vitality of invention, luxuriates in warm sensuous harmonies, revels in a richly varied pianistic touch, and pleasures in the contrapuntal independence of his two hands. If that be mere ‘intellectualism,‘ so be it, although it is much more likely that it is only so in the ear of the beholder.

Bauer, who worked frequently with Tristano during his first years in New York, recalled that Tristano, unlike other musicians, preferred to bypass stating the melody of a tune at the beginning, instead improvising immediately on its harmonic progressions. He asked Bauer not to play rhythm guitar or straight melody, so Bauer had to come up with counter harmonies or counter melodies. It was much more freedom than he was used to, and showed Tristano‘s early commitment to artistic creativity over commercial considerations.

As he settled into New York, Tristano quickly became a favorite of jazz writer Barry Ulanov, co-editor of the music magazine Metronome. For the next several years Tristano would place high in the Metronome polls and some other jazz journals as well, even as controversy raged around his playing, criticized by some as being "cold" and "mechanical," or overly cerebral. Generally considered a "modernist," Tristano could not be fitted easily into any category. Bebop was at its height, and while Tristano was full of praise for its leading light Charlie Parker, he was also critical of the many musicians he heard imitating Parker‘s style. He played with Parker and other bop icons on several occasions, usually as part of a Metronome all-star group. One such date, made at the beginning of 1949, resulted in this tune written by Tristano, Parker, and Billy Bauer, and arranged by Tristano:

That same year two of Tristano‘s young proteges, tenor saxophonist Warne Marsh and alto saxophonist Lee Konitz, were working frequently with the pianist, and also made a recording under Konitz‘s name for the New Jazz label. Jazz writer Ira Gitler relayed a story of the two facing a moment of indecision in the studio when a fellow bop-era musician, pianist Al Haig, stuck his head in the studio door and said, "Why don‘t you guys call the witch-doctor?"…evidence that Tristano‘s cult-of-personality reputation had already taken hold by 1949. "Although they were obviously rankled by the remark," Gitler writes, "this is what they eventually did."

Konitz and Marsh both lived with Tristano at times, as did several other musicians who became part of the Tristano musical orbit. Some even took psychotherapy sessions with Tristano‘s brother. Tristano‘s teaching practice also grew during his early years in New York and would become an important source of income and fulfillment as he began to withdraw from the jazz scene in the 1950s. In 1949, he was at the apogee of his public recognition and activity, and Konitz and Marsh were a key part of his circle and his sound. One Tristano scholar has singled out the ensemble‘s performance on the 1949 Capitol recording "Wow" as an example of how the "saxophones, in particular, play with a phenomenal degree of precision and coordination…they match each other perfectly in intonation and dynamics, and execute the line so cleanly…that there is not a hint of sloppiness."

Two months later Tristano took much the same group back into the studio for another session; when drummer Denzel Best had to depart for a gig after cutting two sides, Tristano and the remaining musicians undertook several experimental efforts that used the same method, or lack of method, that they had sometimes undertaken in rehearsals and live performances. Tristano instructed the others to play without a fixed chord progression, time signature, or specific tempo. The only planned structure was the order of musicians‘ entrances, and a limit of two-three minutes overall to accommodate the duration of a 78 record. Tristano, Warne Marsh later said, told them "to improvise strictly from what we heard one another doing." Barry Ulanov, who was present at the session, called the results "the most audacious experiment yet attempted in jazz" and said that Capitol was so befuddled by the four takes made that the label erased two of them. The other two were released in the next several years only after popular jazz DJ Symphony Sid managed to get a copy of them and began to play them on his show. Here is one of the two recordings now often labeled as the first "free-jazz" experiments in jazz history:

Such recordings contributed even more to the charged atmosphere surrounding Tristano. In 1962 Bill Coss wrote in DownBeat that

During the 1940s the name Lennie Tristano was enough to send almost every jazz critic into a dither of denunciation. The controversy was equal to the furor nowadays caused by Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane in combination. Tristano is a strong individualist who was out of place in the strangeness between two eras.

That strong individualism led Tristano to start his own studio in Manhattan, for both teaching and recording purposes, and also to spurn gigs of any kind that he considered commercial. He discouraged his proteges such as Konitz from taking such jobs as well, and Konitz‘s eventual departure to play with Stan Kenton‘s orchestra in the early 1950s caused tension between the two. Tristano also embarked on another musical experiment that would eventually incite controversy-multi-tracking, or overdubbing himself playing piano lines on top of tracks that he‘d already recorded. We‘ll hear the first example of this practice, along with one of the final apperances of the Tristano-Konitz-Marsh group in its first incarnation, in this next set, starting with the 1951 multi-tracked "Ju-Ju::

Tristano generally preferred, and became somewhat notorious, for his rhythm sections to accompany him and his horn players in basic 4/4 time. Against that foundation, Tristano himself often played polyrhythmic lines. The resulting dynamic tension accounted for much of the drive in Tristano‘s music. Some musicians thought Tristano sounded best in a solo context; Miles Davis once compared him to Art Tatum in that regard. In 1953 Tristano made a recording that was at once solo and not solo, accompanying himself on piano with additional overdubbed piano lines. "Descent Into The Maelstrom" was an attempt to translate an Edgar Allen Poe story of the same title into music, with no harmonic preconceptions, again anticipating the directions that artists such as Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor would take in just a few years. It is also, as jazz critic Larry Kart has noted, one of Tristano‘s "boldest loose-time adventures":

Though many of the recordings that Tristano made in this era were done in his home studio, he did sign a contract with Atlantic Records that allowed himself considerable artistic freedom, and that resulted in two LPs that firmly anchor his recorded jazz legacy. A 1955 album simply titled Tristano captured a Tristano-led quartet, with saxophonist Lee Konitz back in the fold, performing live at a New York City restaurant. The other side included four Tristano piano sides, three of which utilized overdubbing. Although Tristano had done this before, "Ju-Ju" had received only limited distribution through Tristano‘s short-lived self-started record label, and "Descent Into The Maelstrom" would not be released until the 1970s. As critics and listeners became aware that Tristano had, in their view, artificially manipulated these new recordings via multidubbing and speeding up of tapes, some began to charge him with having released inauthentic performances. For Tristano, it was simply a way to achieve a sound that he liked. "Turkish Mambo," with two additional piano parts overdubbed, became a three-metered whirligig of a piece, with one line moving from 7/8 to 7/4, another from 5/8 to 5/4, and yet another going from 3/8 to 4/4. We‘ll hear it now, along with one of the live Tristano-Lee Konitz performances:

Though the Atlantic contract gave Tristano the creative freedom he required, he released only one more LP on the label in the following six years. His teaching occupied more and more of his time and provided most of his income. When Tristano had first started teaching in the 1940s, there had been no road-map for what would come to be known as jazz education. He developed his own system, using various exercises such as having his students listen to and sing along to records and solos by jazz masters such as Lester Young, Louis Armstrong, and Charlie Parker. He is generally considered to be one of the first to teach improvisational techniques; and, as one Tristano scholar has written, "he played a pioneering role in extending the concepts and practices of jazz." His ability to exert such a powerful influence over some of his students contributed to his enduring image as a sort of jazz guru, but Tristano insisted that this was not what he wanted. "My whole scene is to have my students and myself create music that is spontaneous and to be as independent as possible," he said in 1969. In order to do that, Tristano fashioned a system meant to bring the musician to a place where thinking was no longer necessary-where he or she was so skilled and proficient that true feelings and emotion could be translated into musical expression without hindrance. For some, Tristano himself arrived at the artistic summit that he sought on his 1961 album The New Tristano:

Lennie Tristano continued to teach for the rest of his life, though he rarely made any public recordings or apperances after the mid-1960s. He died of a heart attack at the age of 59 in 1978--a point at which he was generally being treated as a footnote to the late-1940s bebop era. Appreciation for his music has seemed to grow in the decades since his death, aided by a number of reissues, box sets, and critical reappraisals-and jazz education, which Tristano helped pioneer, has moved to the forefront of the jazz scene. In 1947 Tristano wrote that "Jazz will eventually become an art form which will be taken seriously by those hitherto unappreciative of it. It will not be held back by the dancing public, profaned by the deified critics, or restricted in its growth by its poor imitators, even when they imitate jazz at its best." That prophecy has proven to be sound.

In March of 1955 Lennie Tristano received a phone call from Dizzy Gillespie, informing him of Charlie Parker‘s death at the age of 34. "Of course I really took it very hard," Tristano later remembered. "I was alone in my studio. And I did something I rarely did, which was to just sit down and play the blues." Tristano recorded himself playing what became known and released as "Requiem"--a piece that shows, once again, that for Tristano, expression of feeling was always the ultimate goal:

More Tristano

- Lennie Tristano: His Life In Music (Eunmi Shim biography)

- Intuition (4-CD box-set)

- The Complete Atlantic Recordings Of Lennie Tristano, Lee Konitz, And Warne Marsh (Mosaic box-set, out of print, with an invaluable essay by Larry Kart, also included in his book Jazz In Search Of Itself)