Dizzy Gillespie once said of Previn, “He has the flow, you know, which a lot of guys don’t have and won’t ever get.

Pianist Andre Previn landed in Hollywood as a teenage prodigy in the late 1940s and began a career that moved through the worlds of jazz, pop, classical, and movie scores. In the 1950s and early 60s he helped popularize jazz-plays-Broadway albums, appeared in a number of West Coast jazz settings, made a series of solo-piano songbook recordings, collaborated with vocalists Dinah Shore and Doris Day, and wrote a memorable jazz score for the first cinematic adaptation of a Jack Kerouac novel. We'll hear music from all of those Previn outings and more on this edition of Night Lights.

In February of 1947, DownBeat Magazine published a profile of a 17-year-old pianist who was causing a splash on the West Coast, as a classical prodigy, emerging jazz musician, and composer, arranger, and performer for MGM's film-score department. "I think this kid, Andre Previn, has a lot of talent and a hell of a good chance," Frank Sinatra told DownBeat, which proved to be something of an understatement.

Previn's earliest years read, appropriately enough, like the treatment of a Hollywood drama. Born in Berlin in 1929, he demonstrated his musical brilliance early on, enrolling at the Berlin Conservatory at the age of 6. But in 1938 Previn was dismissed because he was Jewish, and his family fled Germany, eventually landing in Los Angeles by way of Paris. Previn flourished in California, giving a series of classical concerts when he was just 13. He didn't care much for jazz, thinking of it as "a hotel band with funny hats," he said many years later. Then a record store owner played him Art Tatum's recording of "Sweet Lorraine," and Previn said his ears were opened to the possibilities of improvisation in music. He begin to hang out at jazz clubs and to listen to more jazz pianists such as Teddy Wilson.

At some point word got around Hollywood that this 15-year-old wunderkind was looking for musical work, and MGM summoned him to help with a film called Holiday In Mexico. Previn made his first jazz recordings as well at age 16 for the small Sunset label, a folio of 78s called Andre Previn Plays Duke Ellington which paired him with two stellar performers, bassist Red Callender and guitarist Irving Ashby, who would soon begin working with another of Previn's idols, Nat King Cole:

Though Previn had been working for MGM since he was 16, he didn't get his first screen credit until the 1949 Lassie film The Sun Comes Up. Previn's MGM stint was interrupted when he had to report for military service in 1950; stationed in San Francisco, he was able to take conducting lessons with the conductor of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, which would influence the direction of his later career. Previn soon returned to MGM, where he worked with legendary musical producer Arthur Freed. He continued to play classical music as well. He also married jazz singer Betty Bennett, who served as a connection to some of the best players in the emerging West Coast jazz scene such as trumpeter Shorty Rogers and Shelly Manne. We'll hear Previn in a West Coast jazz context now, starting off with a tune that he wrote and recorded with Rogers:

In 1956 Previn and his frequent jazzmates drummer Shelly Manne and bassist Leroy Vinnegar made what proved to be a highly influential album. Recording for the Contemporary label late in the evening with no prepared material at hand, they took a suggestion from producer Les Koenig to work up jazz versions of a couple of songs from the current hit musical My Fair Lady. The musicians were so pleased with the results that they decided to make an entire LP drawn from Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe's show; since they didn't know enough of the material, Koenig sent somebody out to a record store that stayed open till midnight for a copy of the cast album. Previn, Vinnegar and Manne listened to the album, Previn wrote down the chords, and a few hours later they were done. At the end of the all-night session Previn joked that it would be "the most expensive party record ever made," feeling certain that Lerner and Loewe would never let the label release it "because of what we've done to their nice tunes."

But the record not only came out; it proved to be Contemporary Records' biggest-selling release, and Lerner and Loewe gave copies of the album to all of My Fair Lady's cast members. Dozens of such albums by jazz artists devoted entirely to one show's songs appeared in the next few years, including more by Previn and company, including jazz treatments of the songs from Pal Joey and even L'il Abner.

The success of the My Fair Lady album (Previn would also score the 1964 movie version of the popular musical) may account for the upswing of articles about Previn in the jazz press of the late 1950s and early 60s. He participated in several DownBeat blindfold tests and his jazz albums were regularly reviewed, though critics tended to debate how truly jazz he was—Ira Gitler concluded one review with "Would the real Andre Previn stand up?", an attitude the multi-musical Previn would encounter throughout much of his career. But he was also praised by established writers such as Nat Hentoff and Martin Williams. In the late 1950s he embarked on a series of solo-piano songbook album tributes to Vernon Duke, Jerome Kern, and Harold Arlen, and he later spoke with pride of the Duke album in particular:

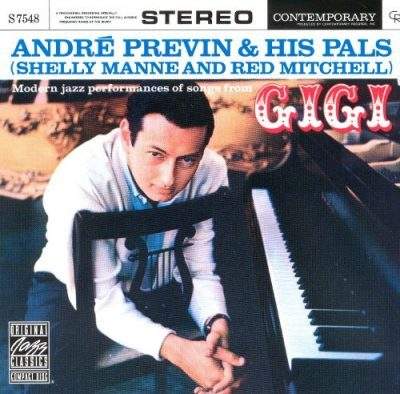

In 1958 Previn, Arthur Freed, and MGM scored a huge hit with the film Gigi, which won Previn his first Academy Award after three previous nominations. He'd net another one for his work the following year on the film Porgy And Bess. "The Freed Unit," as it was called at MGM, soldiered on to another project, an adaption of Jack Kerouac's novel The Subterraneans. The big-budget MGM production of a book depicting a rebellious subculture of young beatniks produced an awkward and stilted result that bombed at the box office, but Previn came up with an excellent jazz score for a film that utilized real-life jazz musicians such as Gerry Mulligan, cast as a hip, saxophone-playing street priest.

Previn left MGM shortly after completing work on The Subterraneans and Bells Are Ringing. He was only 32 years old and wanted to focus more on recording and performing jazz. He was also increasingly working as a classical conductor. Though often touted as an artist who bridged the worlds of jazz and classical, in his interviews and profiles from this time Previn cast a skeptical eye on the Third Stream movement, lauding its goals but often expressing disappointment about the recordings he heard done by composers such as Gunther Schuller and John Lewis. The breadth of his musical realm also extended to working with vocalists, and he made albums with Dinah Shore and Doris Day that rank with his solo songbook albums as the most intimate entries in his discography:

In the early 1960s Previn was still doing work for the movies, and he was in a new marriage to Dory Previn, a lyricist who would collaborate with Previn on numerous songs and several Oscar-nominated film scores. He also had a working trio of several years at this point with bassist Red Mitchell and drummer Frank Capp, and in 1960 they made a first for Previn-Like Previn!, an album consisting solely of his own compositions.

Though Previn had left MGM at the beginning of the 1960s in part to increase his jazz activities, several years later he expressed disillusionment with the current jazz scene in a DownBeat interview, feeling out of sync with the emerging "New Thing" movement, and also weary of performing in nightclubs. He spent much of the next several decades immersed almost completely in the world of classical music, serving as music director for a number of prestigious orchestras. In 1988, however, he returned to jazz with the album After Hours, sparking a two-decade run of renewed jazz activity. Previn passed away on February 28, 2019 at the age of 89. He had won four Academy Awards and 11 Grammys in all—three of the latter for his jazz recordings. Like Leonard Bernstein, whom he'd spoken of with admiration, he was celebrated as an artist who convincingly inhabited several worlds of music. Dizzy Gillespie once said of Previn, "He has the flow, you know, which a lot of guys don't have and won't ever get." Often called "eclectic," Previn fulfilled the most positive meaning of that word.

Extra Andre

- Andre Previn, Whose Music Knew No Boundaries, Dead At 89 (New York Times obituary)

- The Subterraneans: Putting Beats And Jazz On The Big Screen (Night Lights program)