The celebrated classical conductor Leonard Bernstein also won renown for a wide range of compositions, most famously for the musical West Side Story, and counted jazz among his inspirations. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear his music performed by Billie Holiday, Oscar Peterson, Stan Kenton, Benny Goodman, Dave Brubeck and others, as well as some excerpts of Bernstein talking about jazz, all in celebration of the Bernstein centennial.

Has anybody ever successfully embodied as wide a spectrum of music as Leonard Bernstein? Born in Lawrence, Massachusetts on August 25, 1918, Bernstein became one of the first celebrated American composers; he made his conducting debut with the New York Philharmonic at the age of 25 and went on to become its longtime music director, conducting many other renowned orchestras as well; and he wrote symphonies, chamber music, a mass, and songs for Broadway shows, most famously West Side Story. In many ways Bernstein‘s music personifies the diverse and surging modernism of 20th-century American culture coming into its own-confident, searching, and urban. Bernstein protégé Michael Barrett has said that

Bernstein as a composer was the perfect example of why it was important to keep one‘s mind open. His works inhabited so many of our American houses of music: the concert hall, the opera house, the jazz club, the movies, the ballet, the Broadway stage--and even dwellings that defied classification.

After graduating from Harvard in 1939, Bernstein moved to New York City to continue his musical studies, often accompanying friends such as budding songwriters Adolph Comden and Betty Green at the Village Vanguard and other Greenwich Village venues. As he made rapid headway in the classical world, Bernstein also composed the score for choreographer Jerome Robbins‘ ballet Fancy Free, which premiered in April 1944. Bernstein wrote one song with singer Billie Holiday in mind, envisioning a recording of it serving as a prologue to the ballet. Bernstein‘s sister ended up providing the recording instead, and it took Holiday several tries, and arrangements, to nail a take that her label Decca deemed suitable for release:

Fancy Free helped spawn a hit musical the following year called On The Town, which followed the adventures of three sailors on 24-hour shore leave in New York City during the waning years of World War II, with music by Bernstein and the book and lyrics written by Adolph Comden and Betty Green. While the show had its share of Broadway-showcase numbers like "New York, New York," two of the Bernstein-penned melodies that have lingered longest in American jazz-and-popular-song repertoire mine a more reflective and yearning, romantic vein of feeling. Here‘s Blossom Dearie singing the wistful "Some Other Time":

Bill Evans also made a famous jazz improvisation out of "Some Other Time" known as "Peace Piece" for his 1958 album Everybody Digs Bill Evans. And by the early 1960s, it seemed that everybody, jazz musicians included, was digging West Side Story, the hit musical-turned-Oscar-winning-movie with songs by Bernstein and lyricist Stephen Sondheim that updated Shakespeare‘s Romeo And Juliet to a late-1950s, teen-gangland New York City setting. "Maria," "Somewhere," and many of the show‘s other numbers entered the repertoire of numerous singers and jazz combos, and whole albums were devoted to the soundtrack by artists such as Oscar Peterson and Andre Previn. One of the most popular recordings was made by a bandleader Bernstein had made dismissive remarks about in a 1953 DownBeat article, citing him as an example of pretentiousness and comparing his music to "old-fashioned modern furniture; it‘s so moderne!" Nine years later Grammy voters had a different take when they awarded Stan Kenton‘s West Side Story winner in the "Best Jazz Performance--Large Group" category. The album also helped revive Kenton‘s commercial popularity:

While generally emerging as a jazz proponent in the 1950s, Bernstein had strong opinions about the music that he didn‘t hesitate to express. In a 1953 DownBeat Magazine "blindfold test," a regular feature in which musicians were played recordings without being told who the artists were, Bernstein offered mixed responses to music from Duke Ellington, Woody Herman, and Dizzy Gillespie, and rather scathing words for works by modernists Gil Melle and Stan Kenton; the two recordings he expressed unreserved admiration for were by old-guard artists Sidney Bechet and Louis Armstrong. "It‘s so refreshing in the midst of all this contrived mental stuff," he said.

Yet Bernstein also expressed great respect for pianist Lennie Tristano, as cerebral a modernist as ever came along in the 1940s and 50s. Bernstein had a nuanced and eclectic appreciation for jazz that was reflected in his own compositional career; at the same time he was also a wonderful communicator to mass audiences, which accounted for some of his success, and in the mid-1950s he applied those skills to a series of CBS broadcasts for the Sunday-afternoon "Omnibus" program, one of which was devoted to jazz. Bernstein also recorded an entire album called What Is Jazz that explored the evolution of the music, concluding with a recording of "Sweet Sue" by the Miles Davis quintet:

In addition to the What Is Jazz album and television projects, Bernstein also participated in a notable encounter with his beloved Louis Armstrong in a July 1956 New York City concert, conducting the New York Philharmonic as it backed the trumpeter on "St. Louis Blues," with the song‘s 82-year-old composer W.C. Handy among those in attendance:

Bernstein kept up his cultural path-crossings with jazz artists over the next few years; in 1959 he dropped into New York City‘s Five Spot to check out avant-garde sensation Ornette Coleman, sitting in on piano and proclaiming the saxophonist a genius who had superseded the advances of Charlie Parker. In 1962 he faced off in print with drummer Gene Krupa about whether or not symphonic music had been influenced by jazz; Bernstein said that it had, while Krupa took the negative position. Bernstein had already put his beliefs into compositional practice with "Prelude, Fugue and Riffs, a short three-part piece commissioned by Woody Herman for his big band in the late 1940s. Herman never recorded it, but in 1955 the composer revived it for the CBS "World Of Jazz" broadcast, and in 1963 he made a studio recording featuring a friend, clarinetist Benny Goodman:

"Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs" was another example of the multifaceted musical force of composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein, one of the most influential figures of 20th-century American music. I‘ll close out this jazz-and-Leonard-Bernstein edition of Night Lights with music from the two shows that generated the highest volume of Bernstein songs that became standards. We‘ll hear Gerry Mulligan‘s version of "Lonely Town" from On The Town, as well as from Dave Brubeck, who collaborated with Bernstein on the Bernstein Plays Brubeck Plays Bernstein album, which included another Third-Stream-style convergence as Brubeck‘s quartet joined forces with Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic on the four-movement "Dialogues For Jazz Combo and Orchestra," composed by Brubeck‘s brother Howard. The Brubeck Quartet also recorded several songs from West Side Story, including one of its most famous ballads. In retrospective liner notes Brubeck wrote, "‘Somewhere‘ begins with me alone on the theme, with Paul answering one bar later. On the next statement of the theme, it is Eugene who answers, and then Paul re-enters, so that the three of us are playing the theme independently, as in a round. It really works--both musically and as a metaphor. You know, ‘Somewhere there‘s a place for me.‘":

Bonus Bernstein

Watch Leonard Bernstein talk about the influence of jazz in Aaron Copland's 1926 Concerto For Piano And Orchestra before introducing Copland and conducting a performance of the piece at a 1964 Young People's Concert:

Bernstein's performance of "Prelude, Fugue and Riffs" for a 1955 broadcast of Omnibus: The World Of Jazz:

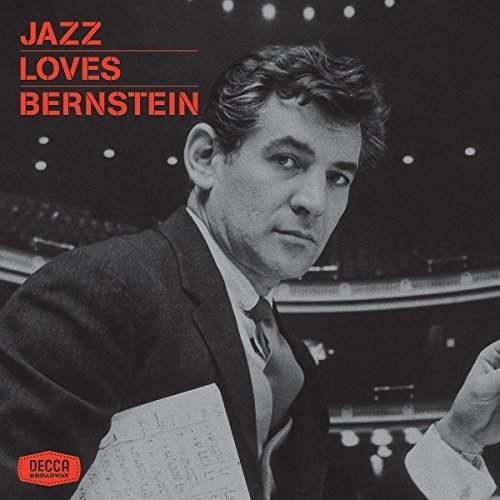

Check out a new anthology of jazz interpretations of Bernstein's music

Listen to WFIU's Afterglow program The Standards Of Sondheim And Bernstein

Read how West Side Story entered the jazz canon