Nancy Wilson, jazz singer-that simple description is one that Wilson sometimes eschewed in the 1960s, and one that jazz critics of the era sometimes were reluctant to apply as well. Looking back now, though, and listening to the records she made with Cannonball Adderley, Hank Jones, George Shearing, Gerald Wilson, and others, it seems indisputable. But Wilson's sound did indeed transcend genres; as jazz blogger Marc Myers has noted, "Her polite, sultry style, her confident phrasing, and her exciting delivery paved the way for Diana Ross, Dionne Warwick, Dusty Springfield and so many other female pop and soul vocalists." Her narrative drive and tone also expanded her appeal beyond jazz audiences; at the height of her success in the 1960s, Time Magazine wrote that "She is, all at once, both cool and sweet, both singer and storyteller." What Nancy Wilson sang in those years was jazz her way.

"Crisp And Clear As A Bell"

Wilson was born in Ohio in 1937 and grew up outside of Columbus, one of six children. Little Jimmy Scott, Dinah Washington, and Sarah Vaughan were all influences in her youth, and at age 15 she began singing on a local television show. She dropped out of college in 1956 and performed for two years with Rusty Bryant's big band, then met saxophonist Cannonball Adderley in New York City, "at the corner of 52nd Street and Broadway, what a cliché," as she laughingly told Myers in 2010. Adderley would prove instrumental in promoting Wilson's career, introducing her to his agent, John Levy, and eventually recording a landmark album with her. After working as a telephone operator and secretary, singing in nightclubs in the evenings, and briefly moving back to Ohio, Wilson finally began to make albums under her own name for Capitol Records, scoring an early hit with "Guess Who I Saw Today," which would become one of her signature songs.

Wilson arrived in the twilight years of the jazz and popular song's mid-20th-century golden age and managed to establish herself as one of the field's most successful and prolific artists of the 1960s, with an engaging sound that eluded genre definition, blending big-band and small-group elements with pop orchestration and doses of soul that could be both big-city hip and suburban cool. Still, jazz was almost always a primary ingredient in her mix. Her second album, Something Wonderful, found her in the veteran company of tenor saxophonist Ben Webster and arranger Billy May, and her third album brought her together with pianist George Shearing, whose long-popular quintet provided a lightly-swinging and inviting backdrop for the young singer. The two formed an easy musical camaraderie, and further demonstrated their simpatico amiability in a blindfold test for Leonard Feather in a 1961 issue of DownBeat. Feather praised their album, The Swingin's Mutual, as "one of the most logical and successful collaborations of the last year."

Not all of the reception for The Swingin's Mutual was positive; DownBeat reviewer Barbara Gardner gave the album a lukewarm review, criticizing what she called Shearing's "thoroughly-stylized society piano group," but praised Wilson's singing, saying

Here are pipes tailor-made for good, emotion-charged blasting and withering story-telling. Her voice is crisp and clear as a bell. It can stand out over the instrumentation or it can melt into the group. Her diction and enunciation are perfect without sounding pedantic. Her tone is sharp without that piercing, cutting edge that plagues so many female vocalists.

Ebony Star

Wilson's next album teamed her up with the musician who helped launch her career in 1959--saxophonist Cannonball Adderley, who had worked with Miles Davis, helped bring other talents such as guitarist Wes Montgomery into the limelight, and was now leading his own prominent soul-jazz group. The recording Wilson and Adderley made has become a jazz vocal classic, and it spawned a hit song, a cover of Buddy Johnson's 1955 composition "Save Your Love For Me," frequently covered by jazz singers today on the strength of Wilson and Adderley's 1961 recording.

The Shearing and Adderley collaborations helped make Wilson a star on the rise in the early 1960s, and in December of 1963 she landed a profile in the pages of Ebony, black America's answer to Life Magazine. "Nancy's fame today is spreading like a wind-swept fire in a dry California canyon," the article proudly proclaimed:

She sings to devotees in New York's Basin Street East, Chicago's Mr. Kelly's, Hollywood's Crescendo, the Carib-Hilton in San Juan, Puerto Rico, the Waldorf in Santiago, Chile, the Copacabana in Rio de Janiero, and other spots from Detroit to Venezuela.

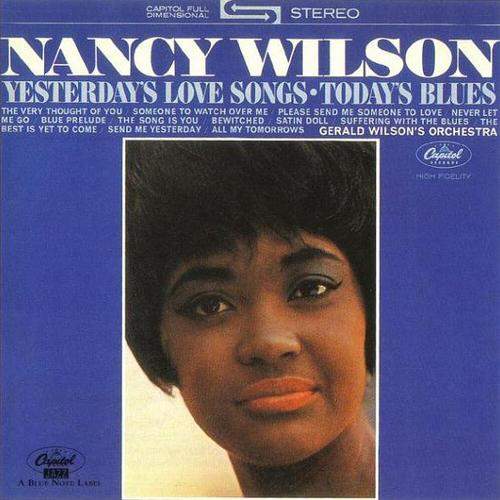

In addition to images of the singer at home in Los Angeles with her husband Kenny Dennis, who was also her drummer at the time, and their child and dog, the article also included photographs of her collaborating with yet another notable jazz figure, big bandleader and arranger Gerald Wilson, for an album called Yesterday's Love Songs-Today's Blues. Dubbed "loud and swinging" by modern-day critic Will Friedwald, the record also showcased Wilson's perennial strength with a ballad on "Never Let Me Go."

Wilson's Hollywood Way

Wilson was a dynamic live performer whose visual appeal drew on more than just her attractive looks; she had a natural theatrical flair and a comfort on camera that led to numerous television appearances in the 1960s and beyond. "Audiences want to see a song as well as hear it," she told Marc Myers in 2010. A 1965 DownBeat review by Leonard Feather of a concert at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles with Gerald Wilson praised the "extraordinary demonstration of the attainment, by a splendid singer, of an almost unprecedented mixture of commercial appeal, physical and musical charm, and artistic integrity." We'll hear an example of Wilson performing live around this time, as part of an all-star 1964 extravaganza at the Hollywood Bowl put on to help oppose a California state ballot initiative that would nullify the state legislature's attempts to end discrimination in housing. It was just one of many activities that Wilson participated in to help the civil-rights movement. Though the initiative passed, it was later overturned by the California Supreme Court.

Hollywood figured in another Wilson project of this period, Hollywood My Way, an LP of songs drawn from movies, which had been preceded by another thematic album, called Broadway My Way. Wilson was beginning to venture more often into the era's contemporary pop repertorie, but she would stay heavily invested in standards as well-and in these years Broadway and the movies were still contributing new songs that would become standards.

"A Song Stylist"

As the 1960s progressed Wilson stayed in the spotlight, both as a singer and a popular-culture figure on television. She was featured once again in the pages of Ebony, in a May 1966 profile with the headline, "Pretty singing star is businesswoman with her feet firmly on the ground." And that was perhaps key to the image of Wilson in these turbulent years, as a singer who could embody big-city hip and suburban cool and sound somehow engaged and reassuring at the same time--emotionally alive, but in control. The article also highlighted her television appearances, domestic life, and emblems of success such as her home and swimming pool.

By now Wilson was cutting down her time on the road, and continuing to downplay any jazz-singer labels, but she continued a prolific recording schedule for Capitol Records, with jazz gems among them such as her collaborations with arrangers Billy May and Oliver Nelson. As the 1960s ended she made one last jazz-centered recording, in a quartet setting with pianist Hank Jones. With the arrival of the 1970s, her music would take a soul-pop turn, and jazz truly would disappear from her sound, though she would return to it in later years. She appeared on numerous TV shows, and she also became familiar to many NPR listeners in the 1990s as the host of Jazz Profiles. She still displayed ambivalence towards the jazz singer label, telling Marc Myers, "I just tell people I'm a song stylist. A song stylist allows me the freedom to sing anything I want. If the lyrics and melody please me, then that should be the only criteria for what I choose to sing."

Jazz Her Way, Extended

- Read Marc Myers' 2010 interview with Nancy Wilson

- Hear Wilson in the previous Night Lights show Jazz Women Of The 1960s

Watch Nancy Wilson on a 1962 episode of Jazz Scene USA:

Nancy Wilson talking to Leonard Feather in 1961 during a DownBeat blindfold test:

Let's get it straight about the jazz singer thing. I don't appreciate the label, definitely, but let's face it: some things I do are very jazz-oriented and some are not... let's just say I am not exclusively a jazz singer. When you say you're not a jazz singer, some people take that to mean you don't like it. I happen to love it; it's just that I happen to know that on some things I am not singing jazz, because there's very little inventiveness. That's all I meant.