In 1963 Eric Dolphy was 35 years old, an accomplished artist still struggling to get by who didn‘t know that he had only a year left to live. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear recordings made by Dolphy in that penultimate year, including live performances featuring his group with pianist Herbie Hancock and a Gunther Schuller Third Stream composition, as well as summer sessions reissued by Resonance Records that reveal Dolphy‘s artistic journey to his 1964 Blue Note masterpiece, Out To Lunch.

You can‘t say that the story of Eric Dolphy, who died at the age of 36 in the summer of 1964, is one of unfulfilled promise. Dolphy left behind a legacy of music that continues to reverberate today, made in just a short span of four years--a period in which he became a figure of inspiration to some and notoriety to others, castigated along with John Coltrane as being "anti-jazz" by a prominent jazz critic, and passionately committed to an artistic path that often left him struggling to pay the bills. Dolphy wasn‘t "anti-jazz"; he was pro-music, and pro-humanity.

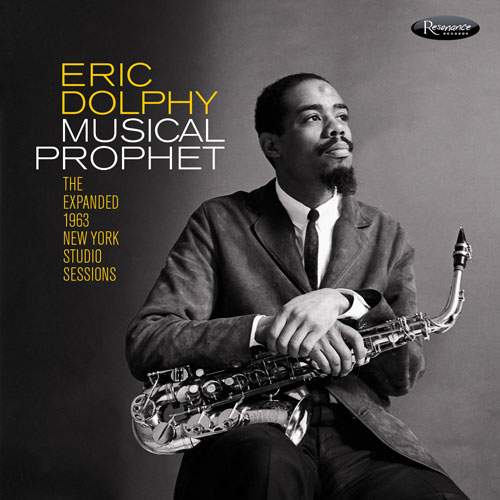

In his essay for the Resonance release Eric Dolphy: Musical Prophet, which documents a peak Dolphy moment in the summer of 1963, musician and educator James Newton describes Dolphy as a

composer/bass clarinetist/alto saxophonist/flutist/clarinetist and bandleader who created a world where the stylistic preferences of straight-ahead, open-form, chord changes, polymodality, tempered pitch, microtonality, jazz, classical and world music, all live unabated within his unencumbered polychromatic artistry. His vision seemed to revel in ignoring the silos where others could comfortably and unreservedly live for their entire artistic lives. At the core of his accomplishments, one finds a fluid, warm, and intensely expressive embrace of cultural plurality.

One example of Dolphy‘s adventurousness was his participation in pianist John Lewis and composer Gunther Schuller‘s Third-Stream project Orchestra U.S.A., which blended jazz and classical approaches into its sound. From February 1963, here‘s Orchestra USA‘s "Milesign," featuring Eric Dolphy on alto sax:

During this period Dolphy was leading his own small groups, which often included a young Herbie Hancock on piano, but he was scuffling to find enough gigs to get by. Some of his income derived from three students who took lessons from him, but one was so poor that Dolphy ended up teaching him for free. There are also anecdotes from this time of Dolphy using his scarce wages to buy groceries for other musicians. Producer George Avakian, who crossed professional paths with Dolphy around this time, later paid tribute to Dolphy‘s generosity, saying that

Eric‘s kindness extended to the way he faced the one big disappointment of his life: the fact that somehow he had not caught on with a big enough section of the jazz public to be able to make a decent living from his music. Lesser musicians borrowed from his bag to get jobs he couldn‘t. But Eric never had a harsh word for anyone who might have given him work but didn‘t. He knew he had to play as he felt was right.

Fortunately some of Dolphy‘s gigs from this era were recorded, and we‘ll hear two of them in this next set-another venture into the waters of the Third Stream at Carnegie Hall, and this performance with his small group at the University of Illinois, featuring Dolphy on flute--albeit slightly off-mike--and Herbie Hancock on piano:

Eric Dolphy heard on clarinet in a performance of Gunther Schuller‘s piece "Densities" at Carnegie Hall on March 14, 1963, with harpist Gloria Agostini, vibraphonist Warren Chiasson, and bassist Richard Davis. Dolphy before that on flute performing his "South Street Exit," with Herbie Hancock on piano, Eddie Khan on bass, and J.C. Moses on drums, from The Illinois Concert, recorded live at the University of Illinois just four days before the Carnegie Hall concert.

Two Days In July

On two days in the first week of July, Dolphy and a talented young cast of musicians laid down the tracks that would be released in subsequent years on the albums Iron Man and Conversations. These sessions, with previously-unreleased alternate takes and one master, have been reissued by Resonance Records in a 3-CD set called Eric Dolphy: Musical Prophet. Most of the music was composed by Dolphy, and it bristles with avant-bop tension and vitality, pointing the way to the Blue Note album Out To Lunch that Dolphy would record the following year, and which is now considered to be his masterpiece. The sessions were produced by Alan Douglas, who had recently worked on several jazz projects including Duke Ellington‘s memorable trio recording with Charles Mingus and Max Roach, and who would later work with rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix. The musicians for these dates included trumpeter Woody Shaw, making his recording debut at age 18, and vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, who would also play on Out To Lunch. One of the sessions‘ most charming and inviting musical sides is a take on a Fats Waller standard that features Dolphy on flute:

As was almost always the case, Dolphy played all three of his primary instruments for these recording dates. On "Iron Man", which became the title of one album when Alan Douglas released it several years after Dolphy‘s death, Dolphy demonstrated his avant-garde-nephew-of-Charlie-Parker prowess on alto sax, driven on by the same group that had backed him on the more lilting "Jitterbug Waltz." Dolphy had already recorded with saxophonist Ornette Coleman and hoped to work with pianist Cecil Taylor, and it‘s perhaps his alto saxophone playing that reflects those musical sympathies best. Jazz musician and educator James Newton compares Dolphy‘s multi-instrumental capabilities to

a visual artist who moves from multimedia to photography, sculpture and painting, each medium providing a different perspective of the artist‘s macro vision as well as embracing various challenges that allow the artist to grow on multiple platforms.

In the next few months Dolphy recorded as a sideman with Charles Mingus, Gil Evans, and a small-group version of Orchestra USA. In early 1964 he appeared on pianist Andrew Hill‘s seminal Blue Note album Point Of Departure and made his own album as a leader for the label, Out To Lunch, that built on the compositions and approach of his summer 1963 sessions. That spring Dolphy rejoined Mingus‘ working group and toured Europe with the bassist, then began to perform on the continent on his own. Shortly before departing America with Mingus, he told writer A.B. Spellman

I'm on my way to Europe for awhile. Why? Because I can get more work there playing my own music, and because if you try to do anything different in this country, people put you down for it.

By the time of his 36th birthday on June 20, Dolphy seemed to be in his musical prime as a player, with Out To Lunch set to hit stores by the end of the summer, and new opportunities evolving for him in Europe. But on June 27, after arriving for a concert in Berlin, Dolphy became ill, and two days later died from what was described as a "circulatory collapse" brought on by undiagnosed diabetes. The jazz world was stunned by his sudden and unexpected death, and DownBeat put him on the cover in tribute; at the end of the year he was elected posthumously to the magazine‘s Hall of Fame.

In the decades since Dolphy's death, his music has come to be loved and respected by many, and as a person he has always been recalled with extraordinary praise. Asked to describe Dolphy‘s personality, his bassist Richard Davis replied, "Quiet, humble, angelic, patient and encouraging." And his questing spirit continues to inspire others as well. As Dolphy once said,

There‘s so much to learn, and so much to try and get out. I keep hearing something else beyond what I‘ve done. There‘s always been something else to strive for. The more I grow in my music, the more possibilities of new things I hear. It‘s like I‘ll never stop finding sounds I hadn‘t thought existed.

Dolphy never stopped searching.

Special thanks to Chuck Nessa.

More Dolphy, More 1963

Dolphy '64 (previous Night Lights program)

NPR review of Eric Dolphy: Musical Prophet

Richard Brody's New Yorker appreciation of Dolphy

Eric Dolphy early 1962-1963 and late 1963-64 discographies with sound files

1963: A Man's Dream, A Nation's Nightmare (previous Night Lights program)

Trane '63: A Classic, A Challenge, A Change (previous Night Lights program about John Coltrane)

Outtakes

More about the new 3-CD set Eric Dolphy: Musical Prophet: