This hour, the third in a series of four programs exploring canons and fugues, from the earliest written music to J. S. Bach – who gets a whole program to himself in the fourth installment. This week, it’s Round Three. Plus, keyboard music of Georg Ludwig Böhm, from a 2013 compilation of Böhm’s complete works played by Simone Stella.

The famous, or perhaps even infamous, “Pachelbel canon” – or more specifically, the “canon” part of Johann Pachelbel’s Canon and Gigue in D Major. So many recordings of this piece, and each one a little different from the others – that one, from a 1986 Deustche Gramophone recording by the English Concert, with harpsichordist Trevor Pinnock.

The Infamous Pachelbel Canon

Can you imagine a world without the Pachelbel Canon? Did you know that it only became really popular after the 1980 film Ordinary People, for which it was the theme? And, did you know that the piece was completely unknown until the early 20th century, when a musicologist named Max Seiffert found it in a library in Berlin? He must have shown it to his colleague Gustave Beckmann, who published it in a musicological article in 1919. There are recordings of the piece out there that last for 3 minutes, and others that last 9 minutes. We don’t know what Johannes Pa-chel’-bel had in mind for a tempo – (and by the way, pa CHEL bel is how his name is said in Germany--not like “taco bell” at all). The piece doesn’t exist in an autograph, or even a copy from the time of Pachel’bel, only in a single source in an unknown hand, probably from the early 19th century, a hundred years after his death. And it bears no tempo indication of any kind.

But heaven knows it’s a canon, or round – because first of all, it’s titled that way, and second, all three parts are fully written out in the sole manuscript. Before the advent of relatively cheap wood-based rather than rag-based paper, a piece like this would very possibly have had its melody written only once, with the word “canon” indicated, either in writing or as a symbol, to tell us where the next player begins.

Now, listen – it’s the same exact bass line, or ground, as Pachelbel. You might notice that Purcell employs the exact same bass line, or ground, and harmonic progression as Pachelbel, aka Pachel’bel, and I certainly hope that you smile several times as you hear “Purcell’s Canon.”

Upon hearing this piece for the first time, a student asked, “What was he smoking?” I suspect that Purcell was “smoking” English music from at least a hundred years before, when “false relations” (that is, for example, playing B-flat and B-natural simultaneously) were an integral part of the English musical landscape – think Byrd, Tallis, and even earlier – and putting his own unique young spin on it. We heard the Ensemble Three Parts upon a Ground playing Purcell’s eponymous canon on their 1993 HM France CD, also entitled Three Parts upon a Ground.

Purcell also composed simpler rounds meant just for fun, such as this one.

The Hilliard Ensemble sang the round "Sir Walter enjoying his damsel," from their 1985 HM France recording The Singing Club. While the 17th century prepared the ground (as it were) for the crowning achievements of instrumental canonic literature, the vocal round saw a significant revival in the English catch collections. The first of these, Thomas Ravenscroft’s Pammelia from 1609, contains 100 works, some of them by Ravenscroft himself, that continue the vocal tradition of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance whose primary function was social rather than artistic. Here is an example of such a round imitating rustic accents and attitudes.

That was the Dufay Collective performing "A wooing Song of a Yeoman of Kent's Sonne" on their Chandos CD from 1995 called Johnny, cock thy beaver. Its provocative title cockily suggests, and correctly so, that 17th century English rounds delighted in double meanings, as we hear in this song about a man who very kindly attached a handle to a woman’s hairbrush.

You get the idea. The Baltimore Consort performed Eccles’ round, or catch, “My man John,” on their 1992 Dorian CD entitled The Art of the Bawdy Song.

After all this fun, perhaps this is a good time for a head-on, somewhat oversimplified but still complex confrontation with terminology. In the Middle Ages, what we now call a canon, or round, was called lots of other things, including “caccia,” “chace,” “rondellus,” and “fugue,” the latter from Latin words meaning “flight,” or “chase.” By the 16th century, only a strictly canonic piece (as we know it) could be called a “fugue.” The term then diverges in the 17th century, when in one part of Italy a fugue had several different contrapuntal ideas, each explored and brought to a cadence, and in another, a fugue had one theme that was exploited throughout the piece.

Now we’ve turned a corner, and instrumental music, unhindered by text, has become an increasingly separate compositional challenge. One way to think of dividing the music is into free, improvisatory, perhaps chordal, often virtuosic, playing versus contrapuntally crafted and perfected separate voices, joining either under the hands of a keyboard player or perhaps as a wind or string quartet of some sort. The terminology and titles of individual compositions often confuse the issue more than clarify it, so let us just listen to a bit of preluding and a bit of carefully-crafted counterpoint, and see whether we can imagine this evolving into a “prelude and fugue.”

Andrea Gabrieli, Giovanni’s uncle, composed this ricercar in the very late 16th century. Listen for entries of a theme that begins with a repeated note, then a rising fifth.

Whoooa - what an ending! Andrea Gabrieli explores a musical idea from all sorts of different angles, some with contrapuntal sections, others with amazing virtuosic outbursts, and yet others more chordal and improvisatory, but all on one theme. You heard Gary Cooper play the Ricercar del settimo tono from Concordia’s 2003 BBC release The Glory of Venice.

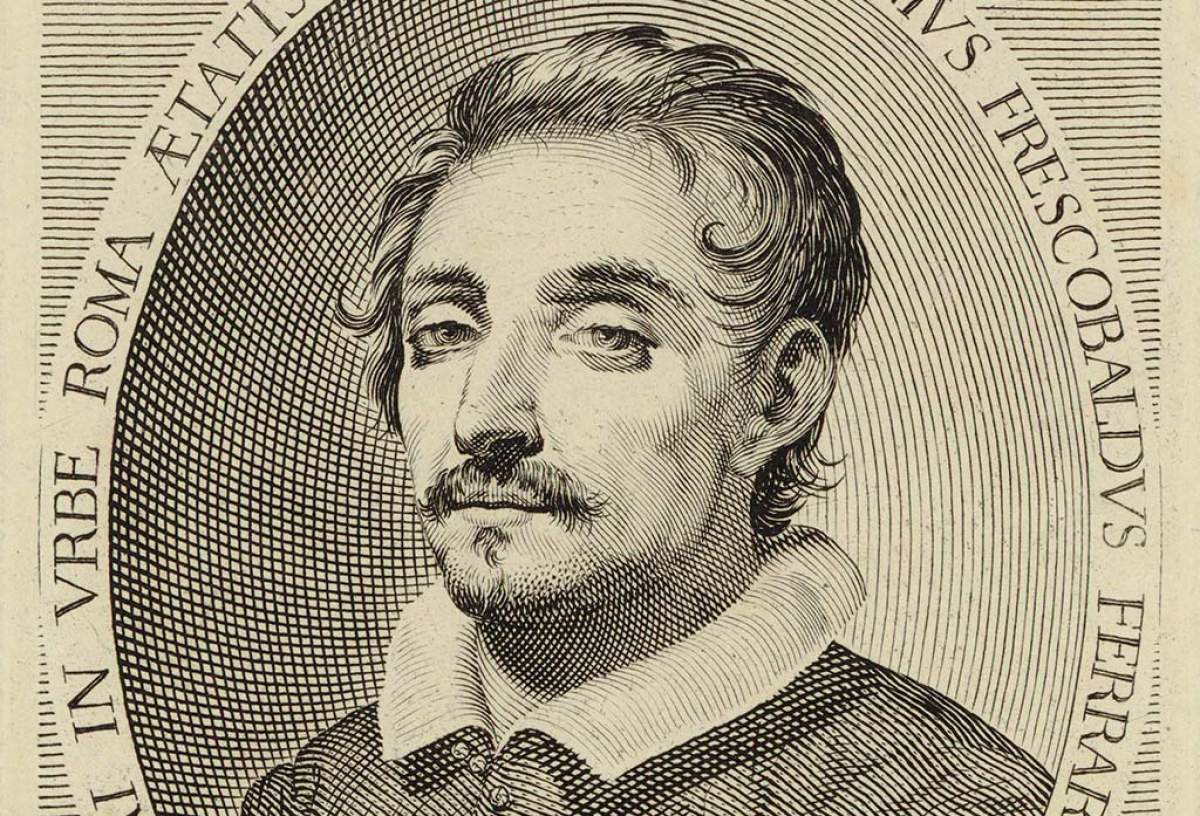

Frescobaldi and Froberger

Girolamo Frescobaldi was the first of the great composers of the ancient Franco-Netherlandish-Italian tradition who chose to focus his creative energy on instrumental composition. Let’s hear what Frescobaldi calls a canzona. One idea is explored throughout the piece in different meters, and the piece is carefully and expertly worked out contrapuntally throughout. Especially at the beginning, does it possibly remind you of, say, a fugue from Bach’s 48? Does the overall shape possibly sound like a sort of miniature “Art of Fugue"?

We heard Frescobaldi’s Canzona Terza from 1627. Gustav Leonhardt played the harpsichord on this 2002 Alpha recording entitled Frescobaldi and Couperin. Were you able to hear different entries of the theme? It is fairly easy right at the beginning, but then gets more difficult as the piece continues. But the theme, with its tiny chromatic twist, is there right to the end.

Alas, if all pieces called “fugue” were collected together and compared, no single common defining characteristic would be found, apart from imitation in a very broad sense. And then there are pieces – like the ones we’ve just heard – that are called something other than fugue.

The mid- to late 17th-century northern German composer Johann Jacob Froberger studied in Italy with Frescobaldi, then went back up north for most of his career. He was exposed to all sorts of current musical practices, and his compositions synthesize Italian, French and German elements.

Andrea Marcon played Froberger’s Capriccio #3, on the 1999 recording L'eredità Frescobaldiana, Vol. II. Calling his piece a capriccio, Froberger uses points of imitation the way a ricercar does – and helps bind together the northern and southern European ideas of what constitutes a "fugue.”

Now we’re really closing in on canons and fugues as J. S. Bach understood them. The next generation in Germany includes the composer Georg Böhm, who was particularly influential on the young J. S. Bach. Let’s listen to a Prelude and Fugue of Böhm.

Georg Böhm: Complete Harpsichord and Organ Music

From the four CD set Complete harpsichord and organ music / Georg Böhm, released by Brilliant Classics in 2013, we heard Simone Stella playing Georg Böhm’s Prelude and Fugue in G Minor on the harpsichord. This collection of works by Böhm, a composer who was a strong influence on J. S. Bach, is also our featured recording on Harmonia this week.

Here’s a chaconne by Böhm, with some striking and rather modern-sounding chord changes.

We heard a chaconne by German composer Georg Ludwig Böhm, born in 1661. Böhm was a strong influence on Johann Sebastian Bach. There is some evidence that Böhm and the younger Bach were friends, and Bach’s son Carl Philip Emmanuel stated in a letter that his father had greatly admired Böhm’s music. One aspect of Böhm’s music was a style known as “stylus phantasticus,” the fantastic style, which featured a strong element of virtuosity and improvisation. Here is Böhm’s Praeludium in D minor, played by Simone Stella, from a CD set on the Brilliant Classics label entitled Georg Böhm: complete harpsichord and organ music.

From a CD set entitled Georg Böhm: Complete harpsichord and organ music, that was keyboardist Simone Stella, playing Böhm’s Praeludium in D minor.

PLAYLIST

News Hole:

Pachelbel: Canon & Gigue/Handel: The Arrival of the Queen of Sheba

The English Concert and Trevor Pinnock

ASIN: B0010X6D0C

Archiv (Deustche Gramophon)

T.1: Canon (4:31)

Segment A:

Pachelbel's canon and other Baroque favorites

Taverner Players/A. Parrott

Warner Classics 2005 / B06XJ7XF7J

Pachelbel

Disc 1, tr. 2: Canon (3:38)

Three Parts upon a Ground

Three Parts upon a Ground

HM France 1993 / B000QQX4O2

Purcell

Track 1: 3 in 1 (5:16)

The Singing Club

Hilliard Ensemble

HM France, 1985 / B0000007N7

Track 10: Purcell: Sir Walter enjoying his damsel (1:50)

Johnny, cock thy beaver

Dufay Collective

Chandos, 1996 / B000000AYV

Track 20: Thomas Ravenscroft: A wooing Song of a Yeoman of Kent's Sonne (2:46)

The Art of the Bawdy Song

Baltimore Consort

Dorian, 1992 / B000001Q93

Track 28: Eccles: My man John (2:18)

The glory of Venice

Concordia, dir Mark Levy

BBC, 2003 / B0012NVT1I

Andrea Gabrieli

Track 6: Ricercar del settimo tono (3:50)

Theme Music Bed: Ensemble Alcatraz, Danse Royale, Elektra Nonesuch 79240-2 [ASIN: B000005J0B], T.12: La Prime Estampie Royal

:59 Midpoint Break Music Bed: Complete harpsichord and organ music / Georg Bohm, Simone Stella, Brilliant 2013, Track 38 Suite in F Major - Gigue (:59)

Segment B:

Frescobaldi and Couperin

Gustav Leonhardt

Alpha, 2002 / B0071X3K8I

Girolamo Frescobaldi

Track 7: Canzona Terza (1627) (3:51)

L'eredità Frescobaldiana. Vol. II

Andrea Marcon, organ

Divox Antiqua 1999 / B00004SREG

Froberger

Track 3 Capriccio #3 (4:18)

Featured Release:

Complete harpsichord and organ music / Georg Böhm.

Simone Stella, harpsichord

Brilliant Classics, 2013 / B00A8QBFMS

Disc 1, tracks 4 and 5: Georg Böhm: Prelude and Fugue in G Minor (6:09)

Complete harpsichord and organ music / Georg Böhm.

Simone Stella, harpsichord

Brilliant Classics, 2013 / B00A8QBFMS

Disc 1, tracks 7, Georg Böhm: Chaconne (3:49)

Complete harpsichord and organ music / Georg Böhm.

Simone Stella, harpsichord

Brilliant Classics, 2013 / B00A8QBFMS

Track 132 Georg Böhm. Preludium in D minor (5:30)