Time capsule for this episode: "Greene Countrie Towne" of Philadelphia

The 26 letters in the English alphabet can be combined to form hundreds of thousands of words. And, like language, music has its own building blocks. Add the 12 notes in the western musical scale together with a few subdivisions of meter and rhythm, and voila! – The past few centuries have left us with more music than we can wrap our brains around! But some of these combinations of musical elements seem to turn up again and again.

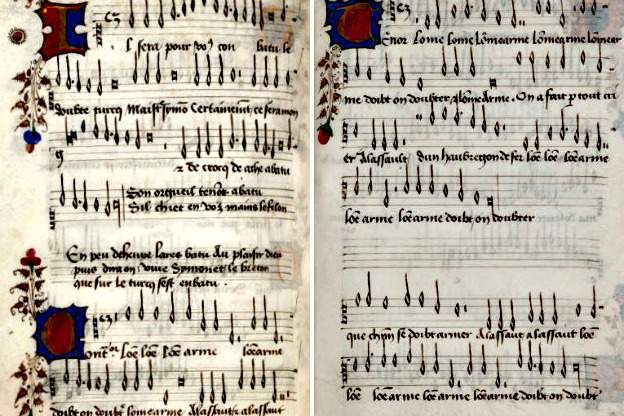

L’homme Armé

Here’s an example. The 15th-century monophonic hit song, “L’homme Armé” is one piece of music that keeps getting recycled.

We’re not exactly sure who first came up with that tune, but by the end of the 17th century, around 40 choral masses had been composed using the “L’homme Arme” melody in at least one of the voice parts. Busnois, Ockeghem, Josquin, Obrecht, Senfl, Palestrina and Tinctoris are just a few of the composers to write a “Missa L’homme arme.”

In Guillaume Dufay’s Missa L’homme Arme, you can find this tune as the cantus firmus in the tenor voice. But don’t worry if you don’t hear it right away because Dufay did not necessarily mean it to be obvious. In most of the movements, the chanson melody is altered, ornamented, disguised or stretched out into very long notes. And, it gets even more complicated in the Agnus Dei movement.

Here, Dufay wrote a riddle in the tenor part, "Cancer eat plenus sed redeat medius," which means "The Crab goes out full but returns half." The famous tune is first played backwards, and then forward again but twice as quickly, imitating a crab’s motion.

Recycling as musical homage

The fame of the Franco-Flemish composer Jacob Arcadelt lies in his madrigals. His first book is a testament to his popularity: initially printed in 1538, it had 58 editions by 1654. Not only that, but several of the madrigals from this collection were rearranged by other composers—recycled as an act of musical homage. One of these recyclers was Diego Ortiz, who, in his Trattado de glosas of 1553, revamped Arcadelt’s madrigal, O felici occhi miei, in his recercadas for viol.

Orfeo

In opera, the same storylines have been re-used over and over and over again. One example is the story of Orpheus and the underworld, which is based on the myth from Ovid's Metamorphoses. Many composers have recycled the plot, each with very individual musical settings.

Two operatic versions of the Orpheus story were especially groundbreaking. Claudio Monteverdi’s Orfeo from 1607 is credited with being one of the earliest, and certainly the most influential in the early development of opera, while Christoph Gluck’s setting, written over 150 years later, is a famous example of the ways in which opera style had been reformed during the intervening years. First performed in Italian in 1762, Gluck presented his Orfeo in French for Parisian audiences 12 years later.

The music we’re going to hear begins at the point in the story when Orpheus has just been told of his beloved Euridice's death. First, we’ll hear Monteverdi’s setting in Italian, followed by Gluck’s version in French. (1:25)

Contrafacta

Contrafactum is a word that refers to the practice of recycling an old tune by setting it to new text. Here are a couple of contrafacta of chant melodies for St. Nicolas that are now about Thomas of Lancaster, who was beheaded by King Edward the Second in 1322.

It was also common for the Church to borrow from popular secular music for its own purposes. At the beginning of the 17th century, Jesuit monks commissioned musician and Latin scholar Aquilino Coppini to come up with contrafacta of some of the most popular music of the time: Claudio Monteverdi’s Fourth and Fifth book of madrigals. In one piece, Coppini recycles Monteverdi’s amorous secular madrigal, Si ch’io vorrei morire, turning it into a sacred love song to Christ, O Iesu mea vita—“O Jesus, my life.”

Featured recording: Treasures from Uppsala

Our featured recording is Treasures from Uppsala, and it includes performances of 17th-century music from the collection of Gustaf Düben, a Kapellmeister serving in the Swedish Court.

Düben collected music throughout his whole life, not only from nearby places but also from afar, giving us an idea of the variety of music that might have been heard in Queen Christina’s court in Sweden.

Here’s the Salve mi Jesu misericordiae for bass voice, violins and bassoon by Swiss composer Johann Melchior Gletle. While this piece is also found in the Düben collection, it’s missing the texted voice part. However, the same music, with a different text, is included as a Salve Regina motet in another of Gletle’s publications. We don’t know whether it was Gletle himself who reused this music with a different text, or someone else—maybe even Düben himself was responsible for the contrafactum!?