(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

KAYTE YOUNG: From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

THERESA MOON: We didn't get any honey until last year, that was our first year of getting honey. We started out with two hives and we had a lot of swarms the first year.

KAYTE YOUNG: This week on our show we visit with beekeepers at a honey sling. We talk with growers v about cucumber grafting and biochemist about yeast hunting and sour beer making. Harvest Public Media has stories on a conservation reserve program, and COVID testing for farmworkers. All that just ahead in the next hour here on Earth Eats, stay with us.

(Music)

KAYTE YOUNG: Earth Eats is produced from the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington Indiana. We wish to acknowledge and honor the indigenous communities native to this region and recognize that Indiana University is built on indigenous homelands and resources. We recognize the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people as past, present, and future caretakers of this land.

Let's go to Renee Reed and the Earth Eats news. Hi Renee.

RENEE REED: Hello Kayte.

Some labor advocates say a recent executive order from President Biden could lead to stronger worker protections in meatpacking plants and other essential workplaces. OSHA must revise its COVID-19 workplace guidelines and consider new emergency standards like mask mandates by mid-March. Labor advocates like Darcy Tromanhauser at the nonprofit Nebraska Appleseed hope the order will make social distancing, testing and PPE enforceable requirements.

DARCY TROMANHAUSER: This is really important because it's showing movement forward and creating a focus on worker safety for the people doing essential work during the pandemic. But what it lands on we won't know for another couple of weeks.

RENEE REED: Biden also asked the agency to beef up its enforcement of protections especially towards employers who put large numbers of employers at risk for COVID-19.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has finalized the rules for growing industrial hemp this year. That means farmers in Missouri, Illinois and other states can get ready for the planting season. Dale Ludwig of the Missouri based Midwest Hemp Association says the rules are fair and will help producers continue to try out the alternative crop.

DALE LUDWIG: We look forward to continuing to grow this industry which it's just really new so there will be a lot of progress made in the next five years.

RENEE REED: The final rules include a longer time to harvest, easier disposal of bad crops and more leniency in violations. Ludwig says right now the biggest market for hemp is for the supplement CBD. He says Midwest farmers won't be able to really see a big benefit in growing hemp until it is more widely used as a fiber in clothes and other products. Thanks to Harvest Public Media's Christina Stella and Jonathan Ahl for those stories. For Earth Eats news, I'm Renee Reed.

KAYTE YOUNG: Many farmers may not reenroll in a conservation program that plays an important role in regenerating soil and water. As Harvest Public Media's Seth Bodine reports, lower payments are influencing their decisions.

MARY CHRIS BARTH: My CRP land is back to the South East.

SETH BODINE: Mary Chris Barth drives down a highway. She's giving a tour of the area and there's golden plains for miles. Barth has many names for this region.

MARY CHRIS BARTH: This is the armpit of Oklahoma. We're on basically the hundredth meridian. And they say the hundredth meridian is where the west begins.

SETH BODINE: As Barth drives she points out portions of land that are part of the conservation reserve program, or CRP. The program works like this. Farmers enter 10 to 15 year contracts and agree not to farm it and add plant species that will help the environment. Occasionally they can make hay or let their cows graze it, in exchange the federal farm service agency cuts them a check for every acre. When it was established in the 80's Barth says it was a hot commodity for the farmers at the tail end of the farm crisis.

MARY CHRIS BARTH: So it was a salvation for a whole bunch of people who were about to lose their property, and they could turn a really good income without significant inputs and save the farm.

SETH BODINE: Today CRP is the biggest conservation program for private land in the country with more than 20 million acres. Barth says the pay used to be good, about $40 per acre. But that's changed in some areas. In her county it's about $18 dollars. The rates are not determined by an arm of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

MARY CHRIS BARTH: It just dropped and dropped and dropped. A significant portion of it will not be renewed this go around just because of the cost.

SETH BODINE: Chad Budy is one of those farmers who won't be renewing some of his land. He has 800 acres of CRP land with 160 expiring soon. Currently he makes $50 per acre, but it's dropping to $19 if he reenrolls. He says he's gonna use the land to graze cattle instead.

CHAD BUDY: I think in our acre, that $19 an acre I think more and more people are gonna fence it and graze it. A lot of land in this area, grass is $15-$25 an acre.

SETH BODINE: Besides the money farmers also have an interest in preventing soil erosion and promoting wildlife. Jessica Barnes and a team from Virginia Tech did a survey looking at why farmers in Oklahoma, Kansas and other southern great states enroll in the program.

JESSICA BARNES: CRP participation is often heavily motivated by an interest in financial stability that at the time CRP, that CRP rental payment that comes annually makes financial sense for the landowner.

SETH BODINE: She says about two thirds of land in that region is set to expire by 2022. But farmers that leave the program don't always go back to plowing the land. Barnes says more than half of those surveyed kept their land and grass. Joy Alspach is the conservation program chief for the Oklahoma Farm Service Agency. At first, she says the amount of land expiring in the next couple of years worried her. But last year's enrollment was good.

JOY ALSPACH: So we had a pretty good percentage that reapplied, and then also our acceptance rate was really high last year.

SETH BODINE: Alspach says keeping erodible land untouched prevents dust bowl conditions. CRP helps with that. She says while it's too soon what enrollment will look like this year; she says she has a good feeling based on past enrollment that soil will remain untouched and in place. Seth Bodine, Harvest Public Media.

(Music) KAYTE YOUNG: Harvest Public Media is a reporting collective covering food and farming in Indiana, Illinois, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, basically throughout the heartland. You can learn more about their work at Harvest Public Media dot org.

Next up we'll visit a beekeeper's club to learn how to extract honey from a honeycomb. That's just ahead after a short break on Earth Eats. I'm Kayte Young, stay with us.

(Music)

Earth Eats has a YouTube channel. Yes, we do. These days my colleague Payton Knobeloch has been posting his recipe videos featuring me, Kayte Young cooking in my home kitchen. We've baked shortbread and savory hand pies, forgotten cookies, a bright carrot ginger soup, and what I like to call the best salad in the world. This week we did a fragrant couscous dish studded with dried fruits and toasted pine nuts.

If that sounds tasty to you, and believe me it is, check it out by searching for Earth Eats on YouTube. You'll find us. Go ahead and subscribe and let us know what you think. You can send an email to EarthEats@gmail.com.

(Music)

Wintertime is downtime for beekeepers. It's a time for waiting, watching, and hoping that your bees have what they need to get through the winter. If they do make it through the cold months and have a successful spring and summer, you might have a chance to harvest some of their extra honey in the fall. A few years ago I attended a honey sling in Bedford Indiana. It's a honey extraction event.

Hi there!

[Narrating] And this one was organized by the Bedford Beekeepers club.

CURTIS MCBRIDE: Open our car door.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Curtis McBride hosts the event in his shop, a large warehouse style building with two industrial fans running nonstop. McBride is the founder of the beekeeper's club.

CURTIS MCBRIDE: I've had bees for years and years but really got back into it since I've retired teaching. I taught school for 34 years. And so I retired from that and really got back into it more. My grandfather had bees when I was a little kid. Of course he died when I was 12 and they sold all of his equipment, so I didn't get any more experience with him after that, but always liked him and enjoyed being around him so.

But I didn't have anybody to learn from, there was nobody around that knew how to keep bees and so once I got back into it this time one of my former students, he had a few bees and he wanted to learn more. So we decided we'll just form a club, and we did and anybody's welcome to come, there's no charge for the club membership. The only thing is if we have some event going on that people will help us with it. We'll have a bee school in January, the last Saturday in January we always have a school there. Last two years we had over 100 people.

KAYTE YOUNG: The club also offers a bee intensive at the Lawrence County Fairgrounds every year with hands on beekeeping workshops and guest speakers from around the country. They share equipment and hold events like this honey sling. They also order packages of bees in bulk.

CURTIS MCBRIDE: 200 packages of bees in this past year from California for people in our club. We brought in 200 last year, and 100 the year before last. So there's some hives getting started around.

KAYTE YOUNG: Club members Theresa Moon and her soon Adam Brown are fairly new to beekeeping.

THERESA MOON: I'm Theresa Moon here with my son Adam Brown and we do the honey stuff together. We didn't get any honey until last year, that was our first year of getting honey. We started out with two hives and we had a lot of swarms the first year. So learning and not really knowing what we were doing, thank goodness we had Curt and people like him to help us who were willing to answer newbie questions.

KAYTE YOUNG: The process of extracting honey is fairly straightforward but first you have to get the honey supers, the part of the hive with all of the honey in it from the bee yard to McBride's shop. Adam Brown explains the process.

ADAM BROWN: We sprayed Honey-B-Gone on a felt board, fume board and place it on top of the hive and they don't like that Honey-B-Gone it's an all-natural, I'm not sure what exactly is in it. And the bees move down plus I smoke them a little bit to try to get them to move down and left it on there about five minutes or so and then kind of shook the box, tried to shake them out of it.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: And then most of them are gone by that point. So then you put them in your truck or what did you do?

ADAM BROWN: I took them and stored them in her garage, stacked them up and covered them up, to keep the bees out of them. I done that Wednesday and Thursday and then we loaded them up this morning and brought them over here.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: Once they arrived in the shop on Saturday morning they start by uncapping the honeycomb.

THERESA MOON: I'm capping honey springs, you gotta scrape the caps off so that the honey can be extracted.

KAYTE YOUNG [INTERVIEWING]: What's the tool that you're using for that?

THERESA MOON: A knife and... what's this thing called?

ADAM BROWN: Scraper

THERESA MOON: Scraper.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Next they load the frames into a large metal cylinder with a wheel type structure in the center. The frames clip onto the wheel. Once all the frames are loaded, they close the lid, start up the motor, and the center wheel begins to spin.

(Sound of machine beginning to whir)

CURTIS MCBRIDE: That's an extractor it holds nine of the frames. What it does it's a centrifuge and it'll spin it and spin the honey out. The bees build in these combs, but the bees aren't straight in a line, the lines aren’t. They're actually tilted just a little bit, the wax is, to hold the honey in. So they get it cured out. Once it's dry that's when we, and it's capped, that's when we take it, and we extract it.

You can see it spinning around.

(Sound of machine whirring more loudly)

And it'll sling that honey out. (inaudible) We'll open this valve and drain it out.

KAYTE YOUNG: Theresa Moon is on the other end of the shop cleaning buckets.

THERESA MOON: The spigot that opens, the strainers will fit right into this and then the strained honey will go right into the buckets and then we can use these to put the honey in jars.

KAYTE YOUNG: The buckets are your typical white five-gallon food grade, but these have sturdy spigots on the bottom for getting the honey into the jars.

THERESA MOON: The beekeeper club has just been great. I mean we've got all the equipment everybody needs if you're just starting out. The first, well maybe the first time we tried to extract any honey we just thought if we cut it off, cut the caps off of them, let it drain it would work but it really didn't. We ended up with very little honey so. Everybody is really nice, works together.

KAYTE YOUNG: Sharing equipment is one of the advantages of joining a beekeeping club like this one, the knowledge sharing is also important. As any beekeeper knows there are many things that can threaten a hive. Lately a destructive pest called a varroa mite has been a big concern for beekeepers across the country. I asked Moon if the varroa mite has been a problem for them this year.

THERESA MOON: Yeah they're a big problem. You can just barely see them so sometimes you don't know you've got them until it's kinda too late. But we treat twice a year in the spring, and we treat in the fall before the winter. Some people don't, kinda survival of the fittest kind of thing but I don't know. Some of this stuff is brought in from other countries and it wouldn't be here naturally. So I feel like the bees, they need a little help, we'll help them.

KAYTE YOUNG: Theresa Moon has plans for her honey.

THERESA MOON: My husband puts it in his coffee. We put it in tea in the wintertime especially, I make kind of an herbal tea whenever we have a cold and put lemon and honey in it, and that's kind of our cough drop, soothy cough drop kind of thing. We use it for that, and I make a granola too that I used to sell at the Orleans farmers' market. But now that I'm not really doing that anymore I make it at Christmas time for family. Honey and oatmeal, oatmeal honey, brown sugar is that one and then there's another one I make that has maple syrup and pecans.

KAYTE YOUNG: Well it must be exciting to be getting this much honey.

THERESA MOON: Yeah, yeah. We're happy to be getting this much honey.

KAYTE YOUNG: In case you're having a hard time picturing it you can see photos of the honey extractor on our website, Earth Eats dot org. That story on the Bedford Beekeeping Club's Honey Sling event originally aired in 2017.

(Music)

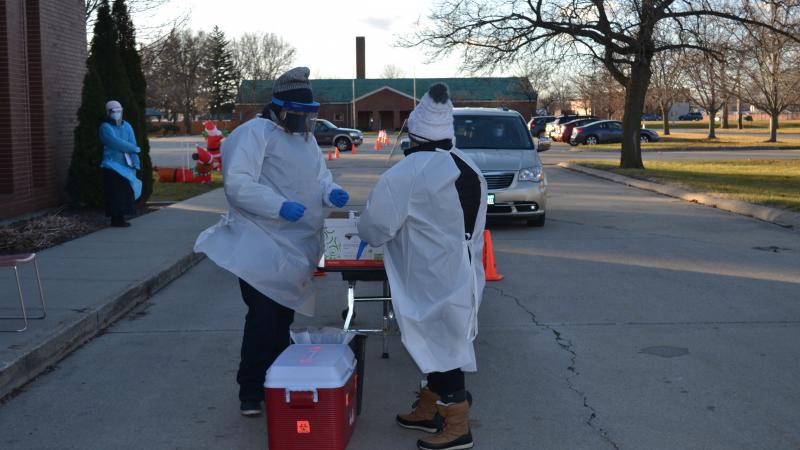

The rollout of the coronavirus vaccine provides hope that the end of the pandemic is near. But it's not over yet. And in some parts of the country access to COVID-19 testing is still a problem. For Harvest Public Media, Christine Herman looks at efforts to address this issue for agriculture workers in a small Midwest town.

CHRISTINE HERMAN: For more than a decade 35-year-old Saraí has been a farm worker. She spends much of the summer and fall cultivating corn and soybeans in the fields of central Illinois. She asked we not use her last name since she's undocumented.

SARAÌ: (Speaking Spanish)

CHRISTINE HERMAN: Saraí says being a farmworker is the most beautiful thing. She hasn't been in the fields lately since she's been focused on getting three kids through virtual schooling. But she says the past year has been devastating to many agricultural workers who've been struck by the virus. Last fall Saraí decided to get a coronavirus test when she thought she might have been exposed. But the nearest COVID-19 testing site is 15 miles away with no public transportation available, and she doesn't own a car.

SARAÌ: (Speaking Spanish)

CHRISTINE HERMAN: Saraí says she borrowed a car from a friend and got her test which was negative, but she thinks the transportation issue probably prevents others in her town from getting a COVID test when they need one. Early on in the pandemic University of Illinois anthropologist Gilberto Rosas was struck by how easy it was for him, a work from home professor, to get tested compared to people working nearby on farms and at meat plants which had big outbreaks.

GILBERTO ROSASARAÌ: We can walk down two flights of stairs, go out the back door and we can get testing whereas these people who are at the forefront who work in the fields, who work in the plants, they lack that kind of access.

CHRISTINE HERMAN: Rosas and his colleagues set out to study what was causing the virus to spread among AG workers. They quickly realized something needed to be done to address this issue of testing access.

GILBERTO ROSASARAÌ: We are doctors but we are not MDs. We are not MDs we are not nurses and recognizing what we lack we began looking for community partners.

CHRISTINE HERMAN: They teamed up with local clinics and began hosting popup COVID testing sites in the central Illinois town of Rantoul. They advertised the vents in English and Spanish and have tried to use their longstanding community connections to bolster turn out. On a recent Monday afternoon Rosas stood in a parking lot in the freezing cold wearing head to toe protective gear alongside clinic staff who screened people arriving for testing.

(Two people speaking Spanish)

They've been frustrated by low turnout at many testing events. At some barely more than a dozen people have showed up. That could be for a number of reasons including fear of a positive result, missing on two weeks of work could be financially devastating says Diana Tellefson Torres who leads the United Farmworkers Foundation based in California.

DIANA TELLEFSON TORRES: We're talking about low wage workers, every penny counts.

CHRISTINE HERMAN: She says in the U.S. there's just not a good safety net for many of these workers.

DIANA TELLEFSON TORRES: When you have to worry about putting food on your own table for your family, sometimes that is the focus because there isn't another option.

CHRISTINE HERMAN: There's also mistrust and fear, especially among undocumented workers who prefer to fly under the radar. So building trust is critically important she says, not just to get people to show up for testing, but also for the vaccine. Torres says she's heard from farmworkers who are eager to get it, but others have reservations.

DIANA TELLEFSON TORRES: One of the big challenges is also like what is this vaccine, what does it contain, what are you putting in my body?

CHRISTINE HERMAN: That's something Saraí, the farmworker in Illinois worries about too. She isn't planning to get the vaccine.

SARAÌ: (Speaking Spanish)

CHRISTINE HERMAN: She says what she's read online made her worry about adverse reactions. But Saraí says if someone she trusted showed her evidence the vaccine is safe; she could change her mind. For Harvest Public Media I'm Christine Herman.

(Music)

KAYTE YOUNG: This story was co-reported with Harvest Public Media's Dana Cronin in collaboration with Side Effects Public Media and the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. Find more at Harvest Public Media dot org.

You're listening to Earth Eats, I'm Kayte Young. Thanks for joining us.

(Music)

Sour beer, are you a fan? Did you even know sour beer was a thing? Either way you'll learn more about it in this next interview. Dr. Matt Bochman is professor of biochemistry at Indiana University. He spoke with IU anthropologist and food scholars Leigh Bush and Maddie Chera about his work with yeast. Maddie Chera gets us started.

MADDIE CHERA: Dr. Bochman could you tell us a little bit about your research?

MATT BOCHMAN: So I'm mostly a biochemist, if I had to put a title on myself. And my lab does a lot of research on DNA replication and repair so the types of things that go wrong that end up giving people cancer or other bad diseases. But we use yeast as our model organism to ask and answer lots of questions in biology and so it's sort of a natural extension of my lab and my hobby and that's where the fermentation science came in.

KAYTE YOUNG [VOICEOVER]: Dr. Bochman does research with yeast in his lab and he also has a business called Wild Pitch Yeast, which we'll hear more about.

MATT BOCHMAN: I moved here to Indiana 2013, summer of 2013 and pretty soon after that started to go yeast hunting for various reasons. And so yea we've got a collection of hundreds of mostly local, mostly Indiana born and raised yeast strains in the freezer and the lab now. And they've got all sorts of interesting what scientists might call phenotypes or what a drinker might just call flavors.

(Maddie Chera, Leigh Bush, Matt Bochman all chuckle)

And we've got ones that make beer sour, and ones that make beer smell like tropical drinks and taste like strawberries and everything in between. And the reason people haven't used these before is basically because of industrialization of beer. Back in the day it was standardized like everything else, that if you use these strains you'll get a consistent product and you'll always be able to crank out that batch of beer and take it to market. But I think probably historically the types of strains we're really rediscovering were probably really common in Europe and elsewhere. And whether it was beer or mead or your favorite fermented beverage.

MADDIE CHERA: If you take yeast from one place and use it to brew a beer in another place, so say you have a yeast from Germany and you bring it to Bloomington, will the local yeasts take over, or will you be able to preserve the flavors that you brought from the other place?

MATT BOCHMAN: So most brewers and that's 99% of craft brewers and 100% of macros, they're all using, well I shouldn't say all, but basically all using European origin strains. So these are things that you know came from Germany, from where loggers were invented, or they're British Ale strains or something like that. And they do single culture brewing. So all they're putting in the beer is this particular yeast. And if it's the Coors yeast, it's locked in a vault somewhere only that Coors people can get to it. And so yeah it's that same flavor characteristic or aromatic characteristic or whatever fermentation character they're looking for from that strain, batch after batch after batch.

But there are breweries that do what's called open fermentation and literally the tank is open to the air, and so they may inoculate it with their favorite strain but then mother nature is gonna sprinkle things in there too. And then really it's just a race to see who can use up all those natural resources in the beer. Brewing strains are really really good, they've been selected over hundreds and thousands of years of brewing to eat sugar really quick and so I would tend to think they'd probably dominate cultures like that. But mother nature's come up with some pretty hardy creatures too. So you never know what's gonna get in there and do some fun things.

KAYTE YOUNG [NARRATING]: Bochman's work involves collaborating with Indiana craft brewers collecting yeast strands for brewing. They call it a bio-prospecting or yeast hunting. They're looking for wild yeasts with desirable brewing characteristics. They brew test batches of beer and conduct sensory analysis of the final products. They also provide yeast consulting, banking and lab services and they've worked with several local breweries and distilleries.

LEIGH BUSH: So it seems like one of the ways that you do this is that you engage with the public in order to get some of these yeast strains through citizen science and working with homebrewing communities. What's the relationship between crowdsourced information and your institutionalized research and I guess also your business?

MATT BOCHMAN: Yeah yeah yeah, those are all good questions. So I mean a lot of science ends up being sort of out of the public eye. Whether it's because people just can't understand it because scientists feel the need to use jargon that nobody can swim through, even their colleagues who are just in a slightly different field. Or they publish in a journal that's not open access and so unless you're at an institution with a subscription you can't to it. But the benefit of the fermentation science really isn't to scientists always, it's really to the people that are fermenting things like homebrewers and craft brewers. So I've really tried to make this as accessible to the people that might want it as I possibly can so I'll archive copies of the papers on my lab website and put them on research gate and we started putting them on bioarchive. So as long as you've got an internet connection you can get to the data.

LEIGH BUSH: That's great.

MATT BOCHMAN: We have funded some of this by crowdsourcing, crowdfunding it. You know the NIH doesn't want to give me money to make beer, so we've had to come up with other ways to fund some of the research. We had I think 60 backers on one of our projects to look at the sour beer microbiome which was really great. And everywhere from my mom throwing in a couple of dollars to craft brewers to just people that think fermentation is neat. I have spun out some of this into a business, Wild Pitch Yeast to try to sell some of these yeast strains we're finding to interested people. Ideally if once we get Wild Pitch Yeast up and running and rolling, you'd be able to buy a collection kit where you'd be able to go to your backyard, or your favorite place outside and find some things and send them in and we'll tell you what yeasts are out there and be able to return them to you to make your own beer.

LEIGH BUSH: So you've mentioned before that you've had to train your nose and tastebuds for describing the beers that you produce, partly because citizens will give different yeast strains to you and then after you isolate and brew with them you have to tell them what you've created. What is the process of training your nose and tastebuds to be able to describe beer like?

MATT BOCHMAN: Yeah so there's lots of different ways to do this, and U.C. Davis has a great sort of sensory program, right this is all sensory analysis. And you basically train yourself on known samples. For instance if you wanna do sensory analysis of beer, beer has malted barley and hops for instance. So you can train yourself on what common hop flavors or hop aromas are so that if you're given a blind sample then you can pick up on what that chemical is. Whether it's in your nose or in your mouth and say, "Oh okay that's a hop essence that I’m getting at" Or "That's what malty is considered as a flavor."

And so some of it's just really, as a beer drinker you're used to these flavors now let's put some terminology into it. The hard part is when you get something that doesn't taste like a normal beer, and then all of the sudden, like okay wait a minute that's super familiar, what is that what is that? And that's where a sensory panel, a number of people getting involved is really handy. So somebody's like "Oh, that's strawberry!" and then that clicks in your head, "That's exactly right!" But strawberry is so far from my normal understanding of beer that I was, my brain was having trouble connecting the two.

MADDIE CHERA: Can you tell us a little bit more about what sour beers are and what developments you've learned?

LEIGH BUSH: Yeah, especially why they have to be kept separate.

MATT BOCHMAN: Yeah so sours are traditionally or generally maybe soured with bacteria. And the bacteria make galactic acid and that's what gives it that tart sour flavor. And if somebody's making an IPA or a brown ale or you know a quote unquote "normal beer", you don't want it to be sour, you don't want it to be tart. That's considered and off flavor.

KAYTE YOUNG: In Bloomington a local brewery called Upland recently built a separate building to produce their sour beers.

MATT BOCHMAN: So for Upland before they actually had a separate facility in the woodshop to make sour beer when they were doing everything in the same place at the same time, they were probably sweating bullets. Because if you get one bacterium in a batch of dragonfly IPA that's enough to ruin the whole batch, and you don't want to dump that down the drain. And bacteria are smaller then yeast and so they can get in the nooks and crannies of all the brewing equipment and they're really hard to clean up. So even with really good cleaning procedures it just takes one cell to ruin the next batch. And so that's why people usually make them in separate facilities, or they just focus on sour beer, or clean beer and they won't mess with the other one. Because they don't want to deal with the headaches.

Our sort of most recent claim to fame I guess is that we found yeast, pure culture yeast that will also sour beer, and you can kill the yeast the same way you could kill any other brewing strains. So Upland might use a California Ale yeast and a Belgium Ale yeast and a German "Heffmaniceman" strain to make three different beers but they don't worry about cross contamination cause they know they've got cleaning procedures that kill those yeast, and these things you can kill the same way. So you can technically now make sour beer and clean beer in the same facility without having to worry or go nuclear when you're cleaning things.

LEIGH BUSH: And I know we have two fairly new cideries, cider makers in town. Is that something that yeast gets involved with as well?

MATT BOCHMAN: Yeah yeah yeah, often times these mead makers and cider makers and sizer makers and kombucha makers and whatever it might be, it's really the same strains that everybody uses if you're at a winery or distillery or whatever. And so actually I was down at friendly beasts the new cidery and introduced myself and left them my card and told them we work with local weird stuff and they seemed excited about that so. Yeah hopefully we'll be able to get involved with more people.

KAYTE YOUNG: That was Maddie Chera and Leigh Bush of the IU Food Institute. Talking with Matt Bochman a biochemist at Indiana University. That interview took place in 2017. Learn more about Dr. Bochman's current research at Earth Eats dot org.

(Music)

January is when gardeners are stuck inside, thumbing through seed catalogs and dreaming of summer tomatoes. This year I am determined to get a good cucumber crop. I've struggled with pests and disease in recent years so I'm troubleshooting and planning ahead. It got me thinking about a story from a couple years ago out at the White Violet Center for Ecojustice at the Sisters of Providence of Saint Mary of the woods in Terra Haute Indiana.

The Center is home to a small-scale farm. It's 5 acres of certified organic gardens, a couple acres of fruit trees, and they raise alpacas for wool and chickens for eggs. The gardens provide the Sisters of Providence with fresh produce, they also run a CSA, sell at the local farmers' market and stock a farm store on site. The center also serves as an educational space and in some cases a place for research.

I was there to hear about a cucumber grafting study. You might have heard of fruit tree grafting, where the upper part of say a peach tree with especially sweet fruit is grafted to the root stock of a type of tree that is known to grow well in a particular area. It's a pretty common practice. I've never thought of grafting cucumbers and I wanted to learn more.

Farm Manager Candace Minster was the person to talk to.

CANDACE MINSTER: So we can walk up to the tunnel, the high tunnels and take a look at the cucumber plants.

KAYTE YOUNG: Okay, that sounds great.

(Sound of gravel crunching underfoot)

CANDACE MINSTER: This one I'm keeping it closed, generally we would have the tunnels open. It's about 54-55 right now and it's overcast but that's plenty warm enough for the cool crops we have, however inside this tunnel we have a grafted cucumber study that we're doing with Purdue University. So these cucumbers don't like to be cold so (laughs) we're trying to baby them along a little bit, so we'll go inside.

(Sound of a door squeaking open)

You can already feel the difference, yeah.

KAYTE YOUNG: (Takes a deep breath) Ah! Smells so good in here. It smells so earthy and...

CANDACE MINSTER: Right? So these are the cucumbers and we're growing two beds of cucumber plants and we have three varieties. And for each variety we have grafted plants and nongrafted plants. We're growing them on a trellis, and we'll train the plants to grow up the trellis and that's a really great tip for anybody even in a home garden. You can really maximize your space by trellising your cucumbers up rather than letting them sprawl on the ground and your cucumbers will stay cleaner and get less insect damage that way.

This is our second year doing a study. The researcher, her name is Weinjing Guan she is originally from China and her area of specialty is in grafted vegetables. And tomatoes have been the superstar of the grafted world for the last few years and now there's a little bit more in the melon industry but cucumbers not so much. So Weinjing's part of a pretty new project really seeing if grafted cucumbers can provide a benefit for organic growers. So specifically what she's doing is taking the top of the, which is called the scion of the cucumber plant that is the desirable plant that you wanna have to harvest. So this Taurus cucumber is kind of a longer style, like an English style cucumber, not huge seeds. And then the root stock is actually a winter squash. And so the little squash plant is grown and then the little cucumber plant is grown and then you decapitate that poor little squash, and you cut that top of that little cucumber, and then you join the two together and you can use the little clip that will fold the two tissues together. So here's one of them. And the interesting thing about these is that as the plant grows it will shed the clip, so it's not so tight that it's going to cause tissue damage.

KAYTE YOUNG: So this sounds like an incredibly delicate process. When I think of a cucumber stem or a squash stem I think of this hollow, watery, delicate thing and especially as a seedling...

CANDACE MINSTER: Yes, it is. So as part of her study Weinjing is doing some ongoing education around cucumber grafting and just really grafting in general so she invited us to go to the Purdue University Research Center outside of Vincennes Indiana and see the grafting process and learn about it and then attempt it. And it is very very delicate. What she's been looking at are the Persian style cucumbers or English cucumbers, the seedless varieties, the ones that can get a little higher dollar value on the wholesale market or even from a regular retail market at the farmers' market.

There are a lot of different factors that you can study for when you are looking at grafted plants and she's specifically looking at productivity and the early seasonality. So the idea behind having them grafted onto the squash root stock is that the squash was more cold tolerant than the cucumber is. So she's trying to determine if that squash root stock will help pass on some of that cold hardiness to the cucumber plant. And then also as the growing season is underway and we're harvesting, we track the weight that we get off of the cucumbers and we also track how many fruit come off of each plant. And then of course running a comparison of the grafted to the nongrafted to see which ones perform the best. There's a lot of record keeping and keeping track of everything as we go through the season.

KAYTE YOUNG: And that's something you're doing here, not the researcher.

CANDACE MINSTER: That's correct. So I already track when we harvest, how much of what we harvest. We tend to take to the same few people that will harvest in here because we're familiar with it, and then that way we can keep that data pretty clean for Weinjing because we want this to be beneficial for her research.

KAYTE YOUNG: One of the things that is hoped for is cold tolerance... could it impact how many fruit you would harvest from each plant? That's a little less obvious to me.

CANDACE MINSTER: Yeah so we noticed last year was the first time we did this, and we noticed with a couple of the varieties that the grafted plants did have a little higher yield. What was interesting to me was that the nongrafted plants were the first to fruit, but the grafted plants even though they didn't fruit as quickly produced more. And over a little longer period of time. So we did see a marked difference in one of the other varieties that we had last season of the performance of the grafted to the nongrafted.

KAYTE YOUNG: So you would not normally be starting a really warm weather crop like that in here, right now, is that correct?

CANDACE MINSTER: That's correct. So everything else that's in here is we have lettuce, carrots, radishes, spinach, arugula, it's all cool season tolerant things.

KAYTE YOUNG: So these are the...?

CANDACE MINSTER: So this side are not grafted. And this side, these are grafted.

KAYTE YOUNG: These are the grafted ones? Okay.

CANDACE MINSTER: So if we get down and you look at the soil level, and just above the soil level you'll see this bump.

KAYTE YOUNG: Yup

CANDACE MINSTER: And that is the grafting join. So right down here this is the squash, and then this is where the cucumber begins.

KAYTE YOUNG: So I can see just from the naked eye that these are taller. They're further along, and it looks like they're fruiting.

CANDACE MINSTER: Yes, yes they are.

KAYTE YOUNG: Or making blossoms or something.

CANDACE MINSTER: They are, yeah and I've been picking off some of the first fruit, those baby fruit. And as we were trimming, pinching some of these off, and this is what we do around here, we're like, "Hm, I wonder if this part is edible? I wonder what this taste like?" And we discovered that these little teeny teeny baby fruit are really tasty. (laughs)

KAYTE YOUNG: Wow, okay. I have tried to eat a cucumber sprout, not good. Tastes really bad, really bitter.

CANDACE MINSTER: Yeah but the really tiny baby fruit are pretty good so you can eat that little guy.

KAYTE YOUNG: I will try it.

(Sound of vegetable crunching)

That's great. That's really good. Tastes like a cucumber. Little mini one, compact.

[VOICEOVER] In case you were wondering why she would pinch off the little cucumbers when the whole point is to get early fruit production it's because late April is too early for the plants to set fruit. These guys were just transplanted into the soil and they've been waiting in pots a bit too long again with the cold spring. So they're stressed. Stressed plants set fruit. It's a survival mechanism. Candace wants the plants to be stronger and healthier before they set their fruit so she's delaying that a bit by pinching them off.

I got Weinjing Guan on the phone to ask about her study. I asked what was most exciting to her about this research.

WEINJING GUAN: Most exciting moment was like this morning I was waking up summer, I'm collaborating with the he has the grafted cucumbers and the normal cucumbers planted in the March this year. And this morning I saw, I'm standing with him we saw the normal cucumbers probably only 10-20% survived, and the grafted plants they all survived. That's very exciting.

KAYTE YOUNG: Planting cucumbers in the ground in March in Indiana. Quite an accomplishment, especially in a cold spring like they were having that year. Weinjing said the next phase is teaching farmers to graft their own seedlings to continue to reap the benefits after the study is complete. I'm not sure if I'm up for grafting cucumbers this year but you never know the lengths I'm willing to go to for a good batch of pickles.

Candace Minster was the garden manager for 10 years at White Violet Center for Eco Justice. She's now the Garden and Fiber Arts Coordinator. Weinjing Guan is a horticultural specialist at Purdue University. That story was produced in the spring of 2018. Learn more about her research at Earth Eats dot org.

(Earth Eats theme music, composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey)

That's it for our show this week, thanks for listening.

RENEE REED: The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Spencer Bowman, Mark Chilla, Toby Foster, Abraham Hill, Payton Knobeloch, Josephine McRobbie, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week Maddie Chara, Leigh Bush, Matt Bochman, Curtis McBride, Adam Brown, Theresa Moon, Candace Minister and Weinjing Guan.

RENEE REED: Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Additional music on the show comes to us from the artist at Universal Productions Music. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.