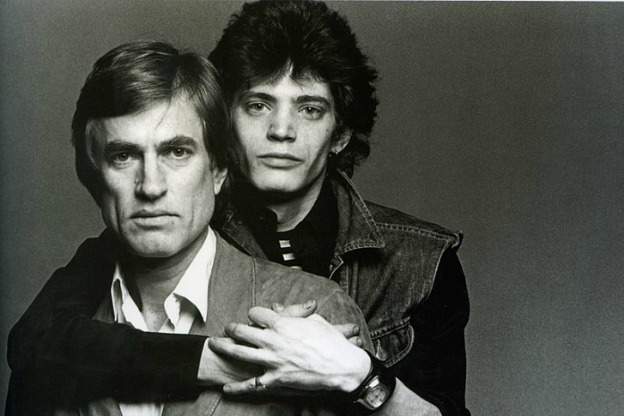

In 2011, the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University received 30 prints from the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. The set includes some of the more challenging images for which the photographer is known, taken in New York's sexual underground during the 1970s and 80s. These pictures are currently having their IU debut at the Grunwald Gallery of Art. Robert Mapplethorpe: Photographs From the Kinsey Institute opened October 10th with a talk by Philip Gefter, longtime writer on photography for The New York Times. Gefter is the author of Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe (WW. Norton, 2014). It's the first major biography of Sam Wagstaff, a name as obscure as Mapplethorpe's is infamous.

Sam was conspicuously known as the lover, mentor, and patron of Robert Mapplethorpe," Gefter begins, "and I always say that was only the last of his distinctions.

"Well, Sam was conspicuously known as the lover, mentor, and patron of Robert Mapplethorpe," Gefter begins, "and I always say that was only the last of his distinctions. I think Sam was a much more influential figure in shaping art history in the second half of the twentieth century than is commonly understood."Â Gefter continues

By the time Sam met Robert in 1972, Sam was 50 years old and Robert was 25. It's commonly thought that Sam sort of scooped him up urchin-like, in Pygmalion fashion, and created this young artist. In fact, Robert had gone to a preeminent art schoolPratt Instituteand had gotten his cultural education at the Chelsea Hotel and Max's Kansas City. So by the time they met, he had a patina of art world sophistication himself . He was no rube in that regard.

A Unique Moment In Time

What happened next was remarkable. In the five years between Wagstaff and Mapplethorpe's meeting and the latter's first solo show at the Holly Solomon Gallery in New York so much had changedaesthetically, and socially.

"In the 1970, it was pre-AIDS, liberated Manhattan," Gefter explains. "There was nothing like it before it or since. It was a unique moment in time," Gefter explains, adding, "the growing respect for photography in the art world occurred simultaneously with the rise of the gay rights movement in America, and that was a coincidence."

The growing respect for photography in the art world occurred simultaneously with the rise of the gay rights movement in America.

Coincidence or not, the confluence of trends positioned Mapplethorpe for stardom.

"Because of the new sexual freedom," Gefter suggests, "he felt freer to make the kind of imagery he wanted."

Creative freedom is one thing, but becoming the darling of the art world, quite another. This could be where Sam Wagstaff comes in. Take the debut show at Holly Solomon, one of the premier dealers at the time-

"Sam did not introduce him to Holly; however, Holly did say she knew of Robert's relationship to Sam, and Sam was a great photography collector, and she wouldn't have touched Robert without Sam. And she said there were other gallerists like [her]."

Bringing Photography Out Of The Closet

But it's more complicated than that. Yes, Wagstaff became known as a great photography collector, however, "Sam credits Robert Mapplethorpe for turning his attention to photography."

Because back in the 60s, when he was curator of contemporary art at the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, Connecticut, and then the Detroit Institute of Arts, Sam Wagstaff certainly wasn't interested in the medium-

"Sam did not think photography was an equal in the art world," Gefter offers. "He thought it was an inferior medium; a kind of applied art. And that was a typical attitude in the art world. Curators and critics and other artists too. That was their basic sentiment about photography."

Most museums and auction houses didn't have photography departments at the timethe Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art having been the two notable exceptions. Photographs were normally relegated to departments of works on papercomprising drawings, engravings, etchings, and other prints.

Photography, Gefter explains, was "hiding in plain sight" in the canvases of the Pop artists-Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Ed Ruscha, just for starters. And even in Mapplethorpe's early work, which appropriated photos from so-called "physique" magazines. Although he had recently been given a Polaroid camera by Metropolitan Museum curator of prints and drawings John McKendry, it was still a novelty for Mapplethorpenot central to his art practice.

"Robert had not even turned to photography when Sam met him," Gefter points out. "He was still making assemblages and collages in keeping with the art-making of the late 60s, early 70s. But he was experimenting with photography and it wasn't until he met Sam that he decided he was going to start focusing fully on photography.

A Eureka Moment

The way Gefter recounts it, Wagstaff also shifted the focus of his collecting after one photograph in particular helped him better understand the medium-

One day in 1973, the two of them went to see a show at the Metropolitan Museum at Art called The Painterly Photograph. In the show was a photograph by Edward Steichen called The Flatiron Building. It was kind of a revolutionary building at the time. That was the beginning of the photograph as being more than simply documentation of subject; but I think, in fact, it was the first moment he understood the subject and the image to be inextricable and of equal weight.

Once Wagstaff saw the light, the long-time collector started buying pictures.

"Until Sam started buying photographs at auction in Europe in 1973-74," Gefter recounts, "there was no art market for photography. Sam created that market."

As Wagstaff's role as a market force took effect, so did the critical acceptance of photography

"Sam became an institution of one. Because he had been a curator in the 60s and had such art world influence, he could cross platforms in the art world, so when he turned to photography, serious curators in high curatorial ranks in major museums started paying attention."

But because of his social standing, Wagstaff's effect was two-fold-

He was born into a notable New York family. His family was on the social register for years. Because he was a patrician and knew very wealthy philanthropists, he could, by virtue of having a conversation with somebody, have them open a checkbook and buy an album of William Henry Fox Talbot's work, at auction...or ten photographs by this young artist named Robert Mapplethorpe.

A Creative Symbiosis

Wagstaff opened his own checkbook for Mapplethorpe, buying him a loft, and a Hasselblad camera, and making introductions for the young artist.

It's the kind of relationship that might raise eyebrows. A cynical observer might point out that Mapplethorpe has been called a master manipulator. He made a point of befriending people in high places. How much of it was a con job? How much of it was Wagstaff being madly in love, and, most significantly, how did the whole art market go for it?

I believe this profoundly, that Robert's work was simply of the zeitgeist. He was identifying something true to his moment. Which is what artists do.

Gefter responds:

When people talk about Robert being a manipulator, I don't think it's so simple. I think Robert was very clear about what he was after. And what he was after was he wanted his work to be seen and he wanted to enter art history in some way. He was simply ambitious, but he happened to have landed in the very epicenter of that world. And he had already landed there before he met Sam.

But you know how things start to snowball. So people walk into Holly Solomon's gallery in 1977 and see these portraits of Princess Margaret and these fancy British heiresses and then Iggy Pop or Patti Smithand by 1977 in New York she was a rock starso all of that participated. There's a confluence of events: it's timing, it's who you know, it's also Robert, and this may be is the key, and I believe this profoundly, that his work was simply of the zeitgeist. He was identifying something true to his moment. Which is what artists do. Serious artists, good artists that is. When you look through the history of art, all of those artists who survived or prevailed, you look at their work today, and you identify something of that period.  And I think Robert's work does that.