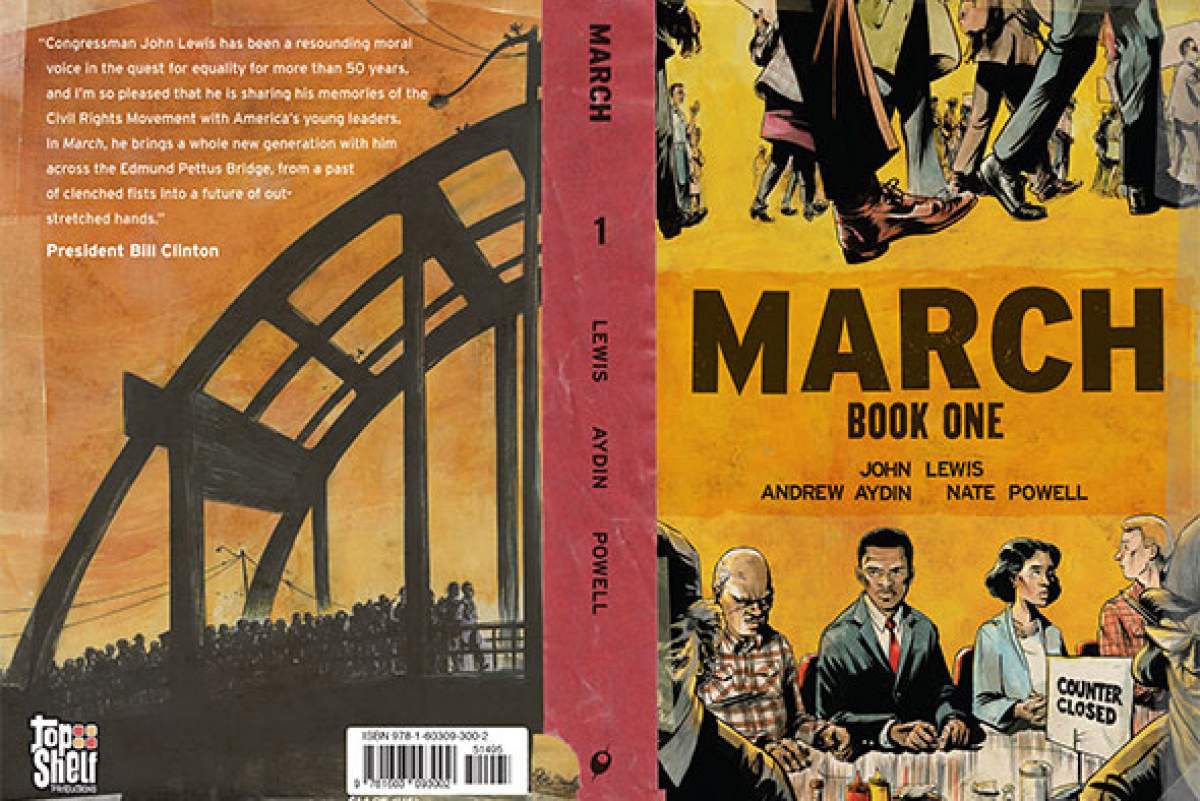

Graphic-novelist Nate Powell's latest book is "March: Book One." The graphic novel chronicles the life of Representative John Lewis. It was co-written by Representative Lewis and Andrew Aydin, with artwork by Powell.

Powell's Previous graphic novels include "The Silence of Our Friends" and "Any Empire." In 2009, Powell's book "Swallow Me Whole" won the Eisner Award for Best Graphic Novel. He lives in Bloomington, Indiana.

James Gray spoke with Nate Powell a few days after "March: Book One" was released.

James Gray: You made some interesting choices with the text. It's not just used as dialogue but as an action. One thing I really enjoy is the scenes where people are singing – the text is used as a banner that joins together different scenes. I was wondering if you could speak to that.

Whenever I'm walking around in the scene in any book I do – that's one of my favorite things is to just "listen" to what's happening and try to translate that visually as best as I can.

Nate Powell: One of the things I'm most interested in as a cartoonist is activating the text component of the comic as much as possible, and really getting it the respect – not just in terms of its aesthetics, the lettering aesthetics, but yet the relationship it has to the pictorial elements. So you have this standard lettering happening when young John Lewis enters the chicken coop, he's quietly clearing his throat, in sort of scratchy, confident lowercase print letters. Then all of the sudden he starts to deliver this sermon to his chickens when a much more readable cursive font starts to come out of his voice. You can sort of feel his speech, all of the sudden, as if it were transcribed on a scroll and as it moves through the night he gains more confidence. You can see a vein sticking out of his forehead, he's getting more gesticulations with his hands, he's closing his eyes, and he starts to yell. So, the little carrots and the little "whispies" that connect different word balloons start to loop around each other and get a little more flair as well. We back away at the end of the scene as we're outside the chicken coop at night, and his lettering is still just as loud as it was – it's still in cursive – but it's got a long meandering tail that slowly winds its way back inside the chicken coop.

A lot of it is learning to subtly control what the reader does as they're moving through the pages of the book, whether that's conscious or not.

Gray:  I think that the way the words express the emotions in the scene is something that makes the entire comic immersive. That struck me with the dialogue and the way it became an action, and not just what someone says. Even with the police – their words look almost like buzz-saws, they're so sharp.

Powell: For sure, and a lot of that is, as a comic book reader, before I really applied it to my own comics, this was something that always gave me a little bit of trouble. My whole life reading comics – the best example being reading X-Men comics – as a basic example you have a telepathic character. There's always this kinda cliché sequence of events and at some point the telepathic character is going to get in a situation where they can no longer keep the thoughts out, and they are being mentally assaulted by other people's thoughts. So I remember in these Chris Claremont X-Men books he would always have this pile of multiple word balloons that's encroaching or threatening these telepathic characters where you'd have 5 or 10 different random people's thoughts, and the words would be sort of overlapped, and cut-off from other word balloons. What was always weird to me was that each of the words was totally readable; they were all done at a very professional standard lettering script.

I guess I started to play around a little bit more with lettering when I started doing a book called Swallow Me Whole which I worked on from 2004 to 2008 and this dealt with kids, with emerging mental disorders and there's a lot of pattern and sensory issues happening within the book as a part of the story. These are teenagers, and they spend a lot of time at school. So, if the main character Ruth would be entering a crowded school cafeteria, all of a sudden, I realized I was in one of these X-Men telepathic situations where I'm basically having to do the same thing, and deal with the overload of other people's voices. Instead of making everything perfectly readable, it occurred to me that, obviously, since we can't hear everything clearly, some things should be lettered a little more sloppily, with a different personality. Some should be readable completely, and some are just scribbles. Then, I realized this is something that can and should be applied across the board whenever possible. Not only to activate a lot of the expressive qualities within lettering, but also to allow you to have a little bit of exploration of the sounds of the story even though you're communicating visually.

Really, it's just a lot of fun, and I've never looked back from it. Whenever I'm walking around in the scene in any book I do – that's one of my favorite things is to just "listen" to what's happening and try to translate that visually as best as I can.

Gray: There's one scene early on where John Lewis wakes up to his alarm and it immediately strikes you how quiet the room is and part of it is the lighting and part of it is the contrast with the the alarm clock and the contrast of the page before…very bright and maybe you would want to describe it…the next morning you can tell how silent it is. I can see that its silent, but what decisions did you make to make the room feel so quiet?

Powell: One thing that's important to describe about this sequence is [that] when I'm writing and drawing my own books- my stories are just kind of "weirdo" stories that are very intuitive and trippy. I use a bit more of a traditional method of laying out my pages that harkens back a little bit to the mainstream of the superhero comics that I grew up on. I like panels, I like delineation but in general my pages are a lot more activated then they are in this sequence. There's a much more dynamic range in size and arrangement of panels on the page.

When we enter John Lewis' house, 5:30 in the morning on a cold January day, for several pages I stick to your standard six-panel grid, which is two panels across, three rows down. More or less it regulates the blood, it regulates your ability as a reader to navigate the situation and so what I'm doing is controlling the flow of time for the reader so they're absorbing each panel in equal measure and they're developing an internal clock and they're putting their guard down, and easing into the room itself. So once the violent explosion of the really loud radio announcer comes over the air, you're still moving through the panels at the same pace because most of it is in this grid formation. You're very aware of how much the radio is intruding on the regular pace that has been established throughout those couple of pages. A lot of it is learning to subtly control what the reader does as they're moving through the pages of the book, whether that's conscious or not.

Gray:  You mentioned Chris Claremont and the X-Men – were there any specific story lines that jumped out to you?

Powell: The single issue that really hit me was New Mutant # 30 something, or #36, and the new mutants are like the young bucks. They were like the 12-16 year old's at Xavier's school. There was some kind of dance going on at another school, and there was some type of bullying happening. There was some type of misfit kid who was getting a lot of crap. Of course it turned out that this person was secretly a mutant, so their freaky-ness was doubled, and I think they went on to end up killing themselves.

Basically, this is before tales of reckoning with bullying became a very hot button issue. I remember really deeply, especially as an emerging misfit as a 7th grader this tale of teenagers being in a position of being called on to be responsible for their collective behavior, which forced this kid to take his own life.

At the end, Kitty Pride, aka Shadowcat, gives this speech at this kid's eulogy and its just a couple paragraphs at the end about the things that make people different, and the ways people are subtly excluded and oppressed, and how its every individual's responsibility to contribute to our society and recognize that everyone has a place in it. I remember being so impacted just by the last page and the Kitty Pride speech, and I remember going in and reading the whole thing to my parents and being like "ALRIGHT" and dropped the mic and left. That was one of the key moments where my parents realized for the first time that comics could have power and gravity. I remember them being sort of like "Whoa…Ok. That was in a comic…alright, alright."

Gray:  What did they say when you read it? What was their response?

Powell:Â I think probably in my Dad's usual delivery where he'd be like "Whoa, heavy!"Â As I left to go draw Wolverine and listen to music I remember them remarking that it was very mature for the content they were expecting, and they were glad that I was into comics.

Gray:Representative John Lewis had a similar experience with a comic book.

Powell: Right. There's this comic called Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story. Its sort of a mysterious 1957 publication which was released by an organization called the Fellowship of Reconciliation and its about the Montgomery Bus Boycotts in the wake of Rosa Park's arrest in 1955. Its actually the impetus for March even existing.

The first major sit-in of the civil rights movement [was] not only directly inspired by a comic, but more importantly, done by 20 year olds with no awareness that it was emerging anywhere else in the country.

Basically, this comic circulated in the late 50s and John Lewis remembers it floating around or reading it and sometimes in interviews people ask "You had a copy?" and he says, "The comic cost 10 cents at the time. I didn't have a copy because I didn't have 10 cents. But some friends of mine had it and it always made its way around."

The interesting thing about the "Montgomery Story" is that its only 14 pages of comics, done in a very silver-age style. In addition to disseminating the information, its also more or less a basic "how-to" of non-violent resistance and organization. It talks about how the Montgomery people went about completely boycotting the bus system for 15 months, and successfully getting the bus lines desegregated.

What's most important about this book is as it's covered in March, in the very beginning of 1960, end of 59', John Lewis and his peers were getting ready to test the waters of desegregating these lunch counters and they had done a couple of test sit-ins, where they didn't actually sit-in, but they were establishing that they would not be served food if they sat at particular counters, or used particular services. They set a date, they said "next weekend we're going to do this, we're going to do our first sit-in".

It happens that at that same time, just a couple days prior to John Lewis and his friends, in Greensboro, NC, there were these 4 college students, just these 20 year olds, got their hands on Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story. It was a weekend, they read the comic and were like, "Whoa. Let's go have a sit in. Let's go have a boycott." They decided that weekend that they were going to go to Woolworth's and what became the first major sit-in of the civil rights movement. Not only directly inspired by a comic, but more importantly, that it was done by 20 year old's with no awareness that it was emerging anywhere else in the country.

Gray: Â When can we expect March: Book II is that going to be next year?

Powell: It should be out either at the very end of 2014 or the very beginning of 2015. Book III will be out in July 2016 for San Diego Comi-Con.

Gray: Â Is there anything you want to highlight in these books? Â Any photos or moments?

Powell: The only thing I'd really like to note is that March: Book I, a good portion of it -  the first half covers John Lewis' childhood; not only his awakening to the world but his awakening to the existence of the Civil Rights struggle growing up on a farm in rural Alabama. He grew up in large family; Mom, Dad, I think 8 siblings, maybe 9, and there's a little photo segment right in the middle of Walking in the Wind, that has about 50 photos total from his birth to 1986. There's only one photo of him as a ten year old boy, and there's one family photo which features all the siblings and his mom and his dad. So when I was really getting in there and I realized that his siblings and his parents would be in this book to some degree, I asked Andrew to check with Congressman Lewis if I could get copies of any photos of his farm, of the house, of his siblings, his kids, and his parents.

It was really kind of a wake-up call because John Lewis said, "I don't have any photos of my house or my family growing up."Â I was like, "Yeah. Well, I guess if it's the 1940's and you're growing up as a farm boy in a large African-American family community in hyper-segregated Alabama: (A) When are you going to have a camera to take pictures haphazardly of your daily life? (B) Who says those photos are going to survive, or that the people are going to catch up with them?"

That was sort of a moment to check my own privilege in being in not only a stable environment but being privileged enough to grow up with a camera around me.  That certainly increased the responsibility of me depicting his family in an expressive way that was also fair, and wouldn't really make too many assumptions since I didn't have too many photos to go by. Also it set the tone for the entire journey through Book One.