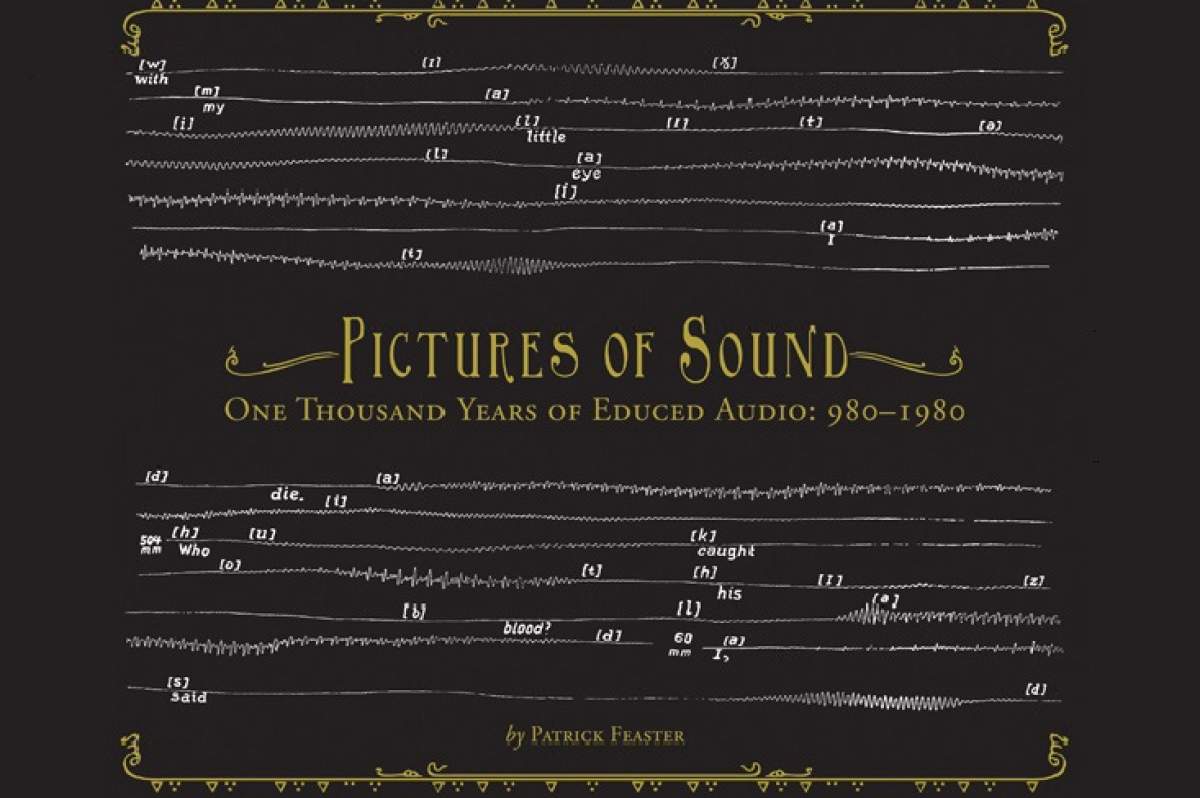

Grammy nominee Patrick Feaster is able to bring sounds back. The Indiana University sound media historian's book/CD package Pictures of Sound: 100 Years of Educed Audio: 980-1980 is featured in the Best Historical Album category.

"The trick," says Feaster, who works with IU's Media Preservation Initiative, "is to get nominatedso you can go to the Grammysbut not to win, so you don't have to get up and give a speech."

The Art of Eduction

Eduction is the process of developing or bringing forward something that is unseen or undeveloped. For Pictures of Sound, Feaster educed audio from imprints of audio transcribed into waves. Many of these were never intended to be played back.

Like this phonautograph of the French folk song "Au Clair de la Lune" recorded by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville:

Lend Me Your Ear

Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville was a proof-reader in Paris during the 1850's.

One day, Scott is proof-reading, and he has a eureka moment. He makes a connection between the way the ear processes sound and the way a tuning fork works. So, he decides that he will to build a human ear.

Feaster says of Scott, "He started from the human ear. He didn't actually use a human ear. Other people did. There are cases in which people used ears of cadavers to make records with. So, people did go down that road, but Scott really was just trying to build a device that was as close to an ear as he could get."

Scott's Invention

Scott wanted his "ear" to be able to keep a record of voices on paper, like the copy of "Au Clair de la Lune" that is featured on this page.

To create a phonautograph, Scott would make this device:

Scott used a metal funnel to focus sound-waves at a piece of membrane, like animal skin. The membrane would then have a stylus stuck into it. This could be a hog hair or piece of a bird feather. When noise was produced on the side opposite of the membrane, the membrane would reverberate with the sound-waves and cause the stylus to move. The stylus would bob up and down and record the wave to paper.

Feaster says, "His idea was [to] get these [performers] to make records in waveforms. People would learn to read them. You could sit down. You could re-experience that great performance, not by turning it back into sound, but just by sitting there reading it, and maybe conjuring it back up in your mind's ear."

However, it was not long before Thomas Edison introduced auditory playback, and Scott's phonautographs were relegated to the footnotes of recording history.

Out of Thin Paper

Scott, and others, left records of the human voice imprinted on paper, and Feaster has found a way to listen to the recordings. I mean really listen to them.

Scott scans the waveforms, and then he repairs them in Photoshop. He can then translate the waveforms from a simple amplitude over duration chart to a spectrogram that displays frequency.

The sound editing software I used to create this story gives me the opportunity to see the waveform of my conversation with Feaster along with a spectrogram of the same audio:

The top half of the session tracks amplitude and duration, while the flame-like spectrogram in the bottom half represents the frequencies of our voices. The more intense frequencies are those represented in the sound file the most visibly.

By translating the sound files from the waveform represented in the top half to the type represented in the bottom half, Feaster is able to acquire enough information to translate a transcription of a sound back into a listenable sound.

Something like this: Au Clair de la Lune

Feaster says, "It lets us hear into the very distant past in a way that's similar to how photography lets us look into the past. It's a special relationship we have to these moments captured in time."