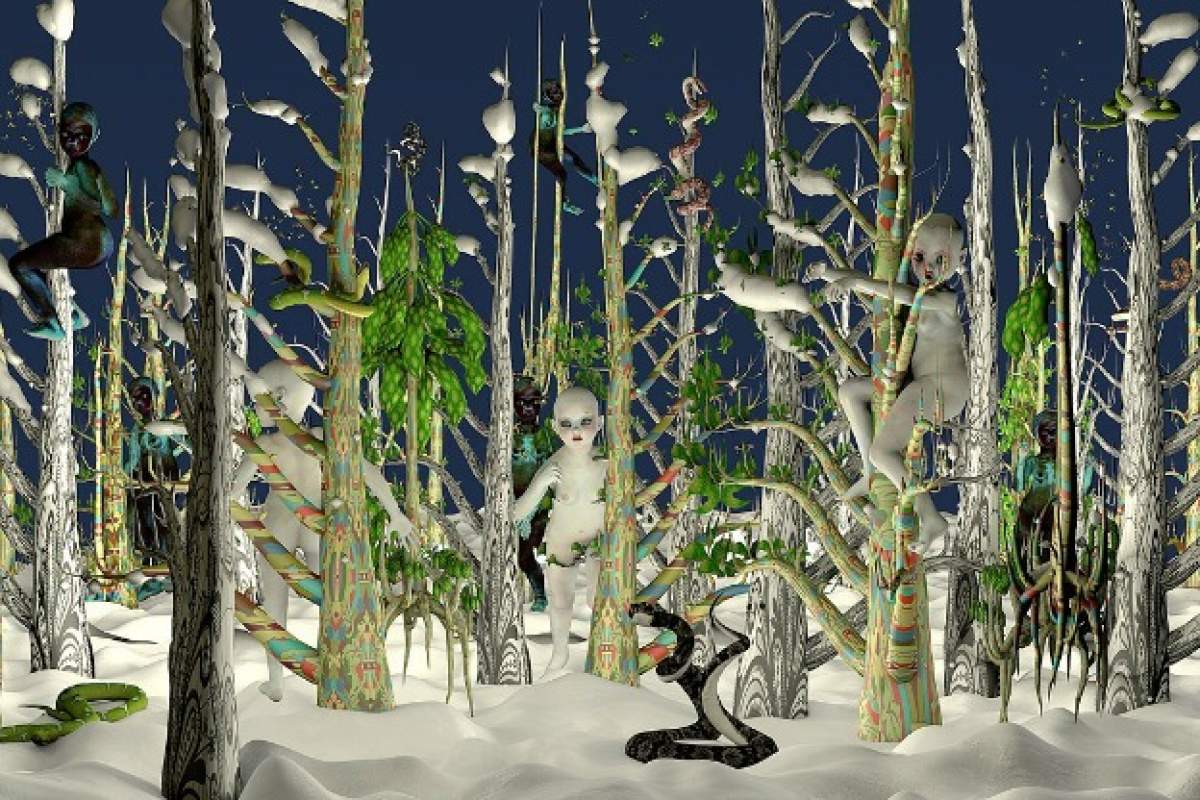

Inside the gallery with Caleb Weintraub's large paintings and life-size installations, you start to think that you've been locked in the It's a Small World ride at Disneyland after hours.

It's as if Weintraub has revealed the shadow side of Disney's multicultural fantasy world. The children of all nations and races decked out in their traditional garb have finally dropped the treacly singing and are running amok. They're riding ostriches and shooting arrows at one another. It seems we've left Disneyland for no-man's land, and it's open season.

It's scary stuff, and it's been even scarier.

Inside the paintings, there is longingnot just for a time when painting mattered, but for a time when things were clear and simple and made sense.

"One time I had a job interview," recalls Weintraub, associate professor of painting at Indiana University. "It was when I was doing much more aggressive, confrontational images, with cherubs with guns and things like that. This one guy, I could tell, was not liking the work very much and was upset by what he was seeing. He looked up and asked, 'Well, what exactly do you do in your classrooms?' and I said, 'Well, I usually hand out a whole bunch of semi-automatic weapons and the last one standing gets the A.'"

Just a little dark humor

"Three of them were laughing really hard and he was not laughing," Weintraub remembers. "I don't think I got that job."

Indeed, it's hard not to see the world Weintraub creates in his paintings, multi-media installations, and digital prints as some bleak dystopian future. The artist concedes the point.

"You know I do find it chilling," Weintraub acknowledges. "I'm not an alarmist about it, but I do wonder about this next transition, if there's another phase of existence. It is a little unsettling."

But more than a prediction, the work is an inquiry.  The children that populate these works represent the uncertainty of the future. And it's not so much the atom bomb or irreversible climate change that keep us from being able to count on things, but a crisis of culture.

They're left with the vestiges of narratives and they're trying to piece together to create their own myth.

"All the mythologies that we've developed as humans over the course of history have been completely mangled," asserts Weintraub. In his paintings and sculpture we encounter a motley assortment of cultural icons, that "could be Saint Sebastian, could be Santa Claus, [or] could be pinatas."

And the children are left to sift through all this cultural debris.

"Maybe the people who came before them had lost their faith in a lot of these narratives," Weintraub suggests, "and now they're left with the vestiges of narratives and they're trying to piece together to create their own myth. But of course that may not be any more sound than the ones that had been jettisoned."

In a way, the fate of the children navigating a world full of heterogeneous cultural artifacts is not unlike that of the painting student, trying to find something to say. Weintraub made fairly traditional landscapes, portraits, and abstract compositions as an undergrad at Boston University.

"Somebody made a comment at some point that the earlier work was starved of imagination," Weintraub recalls. "And I didn't feel starved of imagination but I agreed with the criticism."

Given the intense fantasy of his current work, that criticism is fairly inconceivable. Working alongside video and digital artists in the MFA program at the University of Pennsylvania raised the bar for Weintraub, as did current events.

"When I was in graduate school, 9-11 happened. I don't think it directly relates to the narrative in my work. But it did shake me up in terms of thinking that if I'm standing here playing with crayons as an adult, I ought to really believe in what I'm doing and push it all the way to the end."

Pushing it to the end meant embracing the epic impulses he had repressed in school while acknowledging the rudderlessness of contemporary culture. "Maybe it's about the chaos and despair of not having a narrative," Weintraub suggests.

Embracing digital techniques and multi-media installation is another way of expressing ambivalence about what Weintraub calls the "sticky history" of painting. "I do have an uncomfortable relationship with it," admits Weintraub, "because I think that painting in western history has been propaganda for imperial aims."

So paintin Weintraub's pictures, and the 3-D installationsstars as itself-mountains of multi-colored blobs that weigh down the child figures or punctuate their rituals. Painting is no longer a language, but an artifact in a world cluttered with them.

"Inside the paintings, wrapped in the paintings," explains Weintraub, "there is longingnot just for a time when painting mattered. There's a bit of that too, but it's longing for a time when things were clear and simple and made sense."