It’s easy to forget just how quickly America’s space program – pardon me – got off the ground. The U.S. sent people to the moon less than 66 years after the Wright Brothers first flew at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, and just a little over a decade after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 in 1957.

Ironically, a couple years before Sputnik, the men who would go on to be the faces of the space program were Purdue University students with no thoughts of leaving Earth’s orbit.

“When they were on our campus, the idea of going to the moon was really science fiction,” said journalist, author and Purdue historian John Norberg. “These guys didn’t graduate from Purdue and say, ‘I want to go to the moon. I want to be involved with the space program.’ The space program didn’t exist when they graduated.”

And yet, 14 years after graduating from the university, Neil Armstrong would be the first person to step foot on the moon.

The Hoosier State has been connected to the space program since it began, through Purdue University.

“We’ve leaned into the history of space from the very beginning,” Norberg said. As the writer of eight books on Purdue history, several on the university’s role in aviation, Norberg said Purdue’s status as a leader in space research can be traced back to five clear reasons.

First is Purdue’s engineering program, which is still ranked highly today. Norberg said that in the early days of the space program, engineering experience and education was key to involvement.

In 1945, near the end of World War II, the university saw that the aviation industry would be massive, and the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics broke off from the mechanical engineering school so that Purdue could lead the charge.

Next, Purdue was the first university in the country to own and operate an airport on its campus, attracting aspiring pilots. Third, Purdue had cultivated a strong ROTC program. In the early days of the space program, people were chosen as astronauts after first serving as test pilots for the Air Force.

Fourth is a joint program Purdue hosted with the Air Force Academy in the 60s. When top cadets graduated, they would then come to Purdue for a fast-tracked graduate degree. Seven of Purdue’s astronauts went through the program.

Fifth and foremost is Purdue’s reputation as the “Cradle of Astronauts.” It’s not hard to see where the name comes from: In roughly half a century of the space program, 25 astronauts have graduated from Purdue. They include: Gus Grissom (Class of 1950), Neil Armstrong (1956), Gene Cernan (1956) and Roger Chaffee (1957). Twenty-four have been affiliated with NASA, and the 25th is flying commercially with Virgin Galactic.

“When I go over to Purdue and talk to students,” Norberg said, “at least one student comes up afterward and says, ‘I’m here because I want to be an astronaut, and this is the place to come.”

Grissom, one of the most instrumental astronauts in getting the US to the moon, was the first to graduate Purdue. A native Hoosier from Mitchell, Indiana, Grissom commanded the first manned Gemini mission as well as the first Apollo mission.

Grissom joined the military in World War II with hopes of being a pilot, but the timing didn’t work out. But after graduating from Purdue in 1950, he was offered the chance to become a test pilot, which led to him becoming one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts, out of a pool of thousands of candidates.

Grissom was in a strong position to make it to the moon and would have likely been the first; but in January 1967, Grissom, along with Ed White and fellow Purdue graduate Roger Chaffee, was killed in a flash fire in the Apollo 1 Command Module during a test on the launch pad.

Norberg recalled a story that Betty Grissom, Gus’s wife, told often: The last time she saw Gus, he pulled a lemon off of a tree in their yard.

“She said, ‘What are you going to do with that?’” Norberg recalled, “and he said, ‘I’m gonna hang it on the mockup of the Apollo 1 capsule, because it’s a lemon.’” Norberg added that if the craft hadn’t failed on the launch pad, it probably would have failed later.

“If they had launched that successfully, they might’ve lost all three astronauts in space,” he said.

After the Apollo 1 accident, NASA took over a year to move to the next iteration. They began again with Apollo missions 7 through 12, unaware at the time which one would take them over the edge. When Apollo 10 (with fellow Purdue grad Gene Cernan) got within eight nautical miles from the surface, NASA decided that 11 would be their golden ticket.

“Apollo 10 did everything but land the lunar module on the surface of the moon and get out and walk,” Norberg said.

With that goal in mind, NASA determined Armstrong would command this seminal mission. Considering that Armstrong wasn’t among the original Mercury Seven – and that Buzz Aldrin had campaigned for the chance to be the first on the moon’s surface – the choice was surprising but deserved.

“There wasn’t any X on Neil’s forehead that said he was going to be the first person to walk on the moon,” Norberg said. “But the astronauts I’ve talked to, many of them, say that there was probably no one they could have chosen who was better suited. He just had the personality.”

That personality was a mix of humility and perspective, and it’s one that came through when Norberg asked Armstrong about his “One small step” line on the 10th anniversary of the landing.

“I asked him, ‘How do you feel about that statement?’ He responded, ‘That was not the most important thing I said that day.’

“’Well, then what was?’

“’The most important thing I said that day was, ‘The eagle has landed.’’”

Being able to put the module down and then get it off the ground again had 50/50 odds of success. Norberg added, “Landing on the moon was extremely difficult. Walking on the moon was just for show.”

In the decades following the moon landing, Armstrong was more than willing to give his time back to his alma mater through talks and appearances, and Norberg recalls he was always ready to take photos with students.

Of course, as Armstrong would attest, the space program never succeeded on the back of one or two people. And Purdue’s engineers, scientists and astronauts would contribute immensely to the program long after Apollo 11.

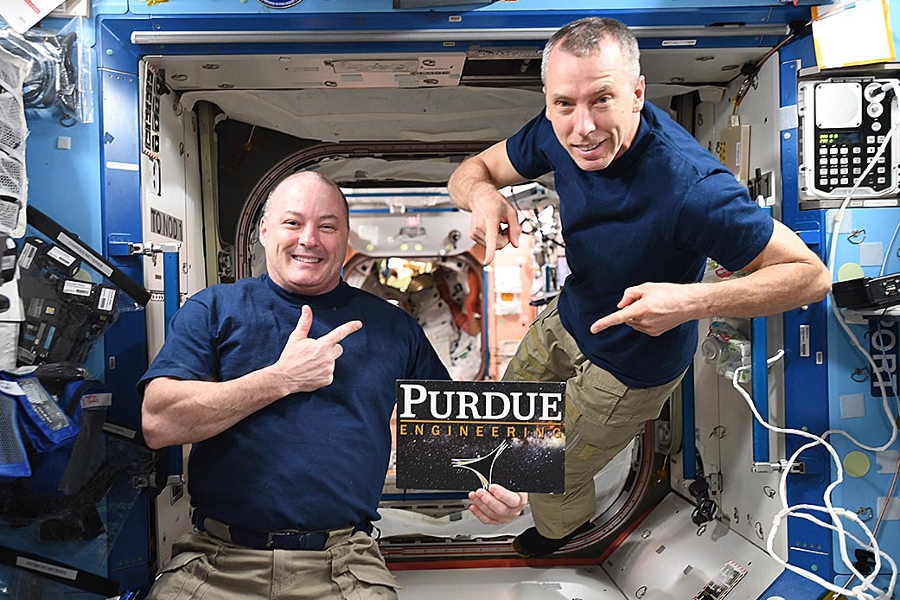

Gene Cernan was the most recent person to visit the moon’s surface in 1972; Charles D. Walker is the first non-government individual to fly in space; Janice Voss set the record for most space flights for a female astronaut at five in 2000; and just last year, Scott D. Tingle and Drew Feustel served on the International Space Station. All of them cut their teeth at Purdue.

Kenneth Bowersox, though not a Purdue alum, also comes from Bedford, and at age 38, Bowersox became the youngest person to command a space shuttle. He, Walker and Grissom all hail from Lawrence County and helped put it on the map.

As we look back on the work and sacrifices that got us to the moon 50 years ago, many are curious about where space exploration will go next.

For some, it’s the long-term goal of exploring and visiting Mars. For others, it’s simply seeing who has the advantage between NASA’s missions and private companies like Virgin Galactic or SpaceX. And even immediate plans to return to the moon by 2024 by way of the Trump Administration’s Artemis program are murky with logistics.

But regardless of what happens and where the space program goes, Norberg says Indiana will undoubtedly have a strong role to play, largely due to Purdue’s close, continuing relationship with NASA. And the pathway to getting involved in the program is getting larger.

“I think [Indiana’s] role could expand, because in the beginning, to become an astronaut, you needed to be a pilot…you had to be an engineer – all these qualifications pulling in different directions,” Norberg said. “Today, there are many different kinds of people who are fit to fly into space.”

He also foresees other universities around the state becoming more involved in the effort. And outside of academia, we’re already seeing the agriculture industry working on methods for growing food in space.

But most of all, Norberg said the next giant leap for mankind could be one we don’t even see coming.

“The most spectacular things that happen are big surprises. Things that we never saw coming,” Norberg said. “There will be things that come from space exploration that will influence our lives very directly. Right now, we don’t know what they are.”

For more information on how Purdue University is celebrating the Apollo 11 landing itself, head to their website.