Want To Address Teachers’ Unconscious Biases? First, Talk About Race

Ayana Coles, rights, sits with students at Eagle Creek Elementary School. At Eagle Creek, students of color make up 77 percent of the student body, and all but four of the school’s 37 staff are white. Coles has led conversations about race with colleagues throughout the year. (Peter Balonon-Rosen/Indiana Public Broadcasting)

INDIANAPOLIS — As Ayana Coles gazed at the 20 teachers gathered in her classroom, she knew the conversation could get uncomfortable. And she was prepared.

“We are going to experience discomfort — well, we may or may not experience it — but if we have it that’s OK,” said Coles, a third grade teacher at Eagle Creek Elementary School in Indianapolis.

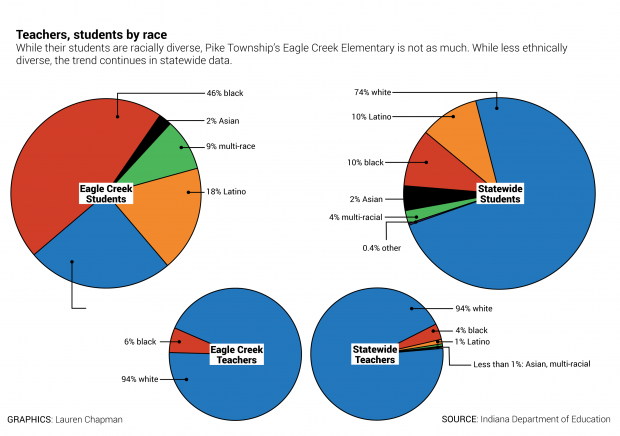

At Eagle Creek, students of color make up 77 percent of the student body. All but four of the school’s 37 staff are white. Throughout this past year, Coles has led a series of after-school discussions with teachers about race.

- Teacher Racial Biases Affect Students' Education, So Let's Talk About ItThe majority of the workforce in schools are white, regardless of how many minority students a school has. This often means white teachers’ unconscious biases come out in the form of discipline toward students of color.Download

“We talked about unquestioned assumptions,” Coles said to her colleagues at the meeting. “Like some parents or groups of people have no value of education, or their parents are uneducated, their parents don’t have money.”

Her goal? Create a common understanding of race and power, with the hopes that teachers acknowledge, then address how that plays out in the school.

But getting there means first exploring often-taboo topics: race, power and teachers’ biases.

Unconscious Biases

Different biases effect us in different ways, yet many overlap.

To give a few common examples:

- We may pay attention to things that justify preexisting beliefs — confirmation bias.

- We may favor people like us — ingroup bias.

- We may expect members of a group to act a certain way — stereotyping.

But what happens when these, or other biases, are implicit. In other words, they’re unconscious but still affect our outlook and behaviors?

According to study after study after study, teachers’ behaviors — often directed by conscious or unconscious biases — affect students’ lives, from student discipline to promotion.

Nicole Goodson, a staff attorney with Disability Legal Services of Indiana, works with many students who have been suspended or expelled from school.

“We do see a disproportionate number of minority cases,” Goodson said.

Many of her clients are black and Latino boys.

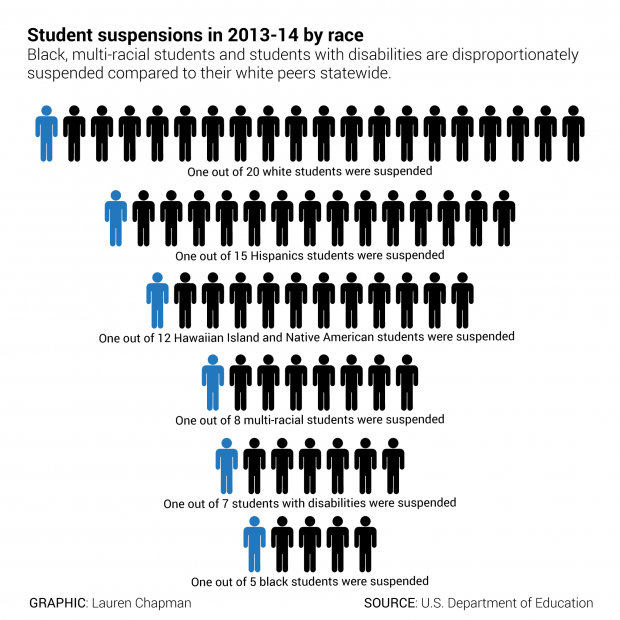

In Indiana, black students are suspended at four times the rate of their white peers. Schools, on average, suspend one in 20 white students, but one in five black students — and almost one in three black boys, a StateImpact analysis of U.S. Department of Education data shows.

Schools often suspend those students for non-violent reasons, according to Goodson.

“Not necessarily behavior that puts anyone at risk, but maybe not following the rules exactly as they’re written,” Goodson said.

Reasons like “non-compliance” and “disrespect.” Situations that require a judgment call.

And that’s important to acknowledge in Indiana, where 94 percent of educators are white.

Because what happens if one’s attitude towards race, and those biases mentioned above, unconsciously cloud that judgment?

The ‘Courageous Conversations’

Back at Eagle Creek Elementary School in Indianapolis, Ayana Coles and colleagues were deep in conversation about race and power.

The meetings aren’t part of any larger program. Just a group of teachers getting together voluntarily, for what Coles calls “courageous conversations.”

Music teacher Jason Coons told the group he felt bias can be a two-way street. He’s white, and almost four out of every five students at Eagle Creek are students of color. He said he thinks students come in with biases about him.

“As a white heterosexual man, that’s a lot of what they see,” Coons said. “And if they’re hearing at home how I’m the enemy… At the end of the day I’m just frustrated with the fact that I don’t feel like I can do anything about it.”

“Here’s what I’ll tell you,” Coles said, “I have no answer for you. I am not the end all be all. I have no answer. But this is what I will tell you. I was absolutely taught to not trust white people. It is hard for me to trust white people. And I’m being dead serious. Until I got to college — ”

“I was taught not to trust black people, so…,” Coons said.

“I get it,” she said, with a laugh.

Both Coons and Coles agreed that their upbringing influenced those thoughts, but that they’re not rigid — they’ve both grown and changed.

Yet, historically, white people have had the institutional power to create policy, social stigmas and programs based on those kind of biases, Coles said. Black people have not.

And understanding that difference, Coles said, can help teachers identify how that plays out in their school building.

A Specific Example: Language

“I actually had someone ask me, ‘Why don’t black people speak right?'” said Dorothy Gerve, speech pathologist at Eagle Creek Elementary. “And it threw me…”

[pullquote source=”Dorothy Gerve, speech pathologist”]”I actually had someone ask me, ‘Why don’t black people speak right?'”[/pullquote]

Gerve and Coles were the only black teachers present.

“So, a lot of our kids use ebonics,” Coles said.

Language alone can trigger biases, said Cole: Who’s smart? Who’s not?

“How do we then bridge that gap between ebonics and standard English?” said Coles.

But some, like kindergarten teacher Robin Lawrence, were hesitant.

“I don’t think we should go so far as to say, ‘Well that’s you, so you don’t have to learn the standard way,'” Lawrence said.

Coles agreed, but said, even so, some teachers may not see the full picture.

“I think that the problem is that — I’m just speaking for myself and not all black people — but I can remember being younger and if I used standard English, I’d feel like I was acting white,” Coles said. “And so I was opposed to it because I wanted to embrace my culture and heritage.”

Coons, the music teacher, said since the after-school conversations, he’s started looking at things differently.

“Like what I think is misbehavior,” Coons said. “And I’m not trying to sound like some hippie or something, but like, OK, is this really actually something that needs to be addressed or is this just because it’s so different from what I grew up with that I view this as offensive?”

He said he’s still learning.

“I’m also just on my own little journey as well, you know,” said Coons. “I’m thinking about the kids, but I’m still growing as a person quite a bit, too.”

An Impact On Student Lives

A recent study from Indiana University researchers looked at the students recommended for gifted and talented programs across the nation.

It found black students were three times more likely to be identified as gifted if that call came from a black teacher, not a white teacher.

“Expressions of learning may be different,” said Jill Nicholson-Crotty, an associate professor at Indiana University”s School of Public and Environmental Affairs.

She authored that study.

“Because that’s what we grew up with, doesn’t mean everybody did,” Nicholson-Crotty said.

Ayana Coles sits with her students at Eagle Creek Elementary School. (Peter Balonon-Rosen/Indiana Public Broadcasting)

For Students, A Growing Outlook

Eagle Creek administrators praise the after-school meetings. The school and the “Courageous Conversations” were recognized by the Indiana Department of Education as a promising practice that encourages culturally relevant teaching.

Third grade teacher Ayana Coles said she plans to continue these types of conversations next year, with both staff and students.

She was surprised by how comfortable her third-grade students were talking about power and perspective.

“They’re honest,” said Coles. “They’re just like, ‘This is what I think, so this is what I’m going to say.'”

And Coles’ students say discussions about those topics helped change the way they think.

“You can have power for any perspective that you have,” said Lynae Gude, one of Coles’ third grade students. “Like if you look at the world and you see negativity you can be an advocate and say something about it.”

Nine-year-old Lynae is heading to Puerto Rico this summer with her family. She’s nervous about flying, but said she has big plans for the future when she gets back.

She shared one last assignment with her peers: a letter to her future self.

“‘Dear Future Lynae,'” Lynae said. “‘One thing about you is that you are a 24-year-old activist…'”

She said she’ll be an activist and teacher.

“‘You talk about fairness and how you feel about the world inside. Your family lives in a safe facility,'” Lynae said. “‘Hope this ends up to be a perfect life. Follow your dreams future me. Sincerely, yours truly, 9 year old Lynae.'”