How NCLB Waivers Are Changing Which Schools States Target For Improvement

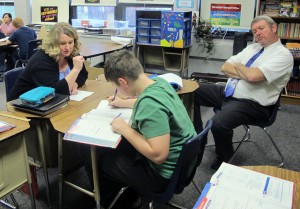

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

Rockville Elementary Principal Jeff Eslinger, right, watches as a sixth grade teacher helps a student with a math lesson. A turnaround specialist from the Indiana Department of Education is tracking implementation of the school's improvement plan.

States that have sought flexibility from the federal government in the form of waivers are using very different criteria to target underperforming schools for intervention than they did under No Child Left Behind.

That’s according to a recently released report from New America Foundation policy analyst Anne Hyslop, who compared accountability under NCLB to state-led efforts the next school year.

Hyslop writes that under the new system, the choices individual states made about how to design an accountability system mattered less than the fact the federal government dictated states intervene in 15 percent of Title I schools.

“So it was shifting from an absolute system of accountability to one that was all relative — essentially, we’re now grading schools on a curve,” Hyslop tells StateImpact.

But while most states Hyslop studied identified fewer schools in need of improvement under the waivers, Indiana actually designated more schools as “focus” and “priority” after appealing to the federal government for flexibility.

Part of the reason is because Indiana wasn’t intervening in 15 percent of Title I schools before, says Hyslop, and had to do so to meet the requirements of the new waiver policy. But perhaps more importantly, Indiana also set absolute, rather than relative, goals for school improvement.

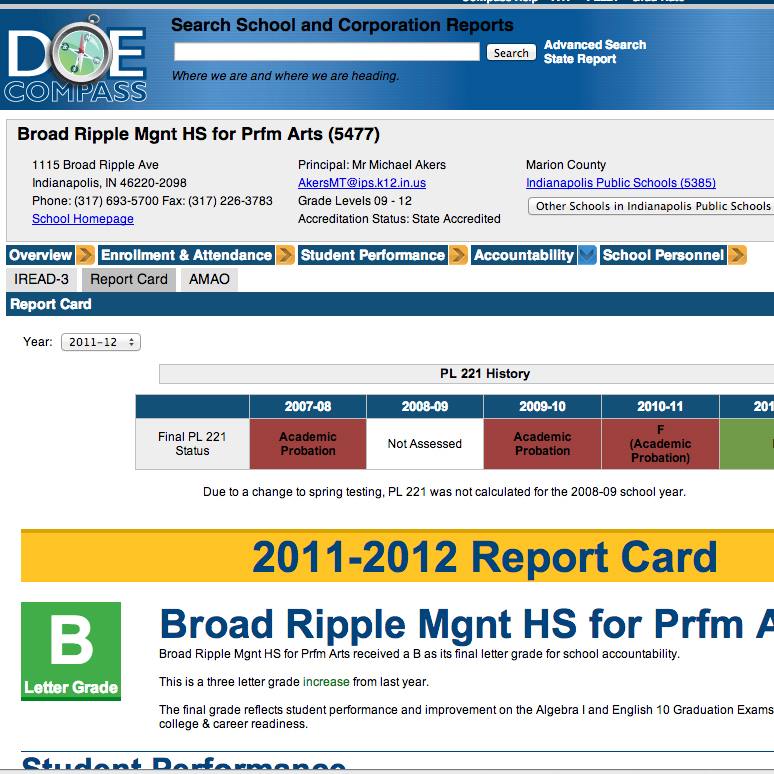

“If you’re a D school, you’re a focus school. If you’re an F school, you’re a priority school,” she says. “Most states didn’t do that. … If 15 percent of schools is 100, once they get to 100, they stop. They don’t look at school 101.”But even though Indiana bucks the trend on identifying schools for improvement, Hyslop says the state’s NCLB waiver has changed which schools are being targeted. She points to three schools in Michigan City who all saw significant movement when Indiana added student growth data to school letter grades in 2011-12:

Knapp Elementary was not the only school in Michigan City caught in limbo between NCLB and waivers. Nearby Pine Elementary School, a school that had received two straight “A’s” for exemplary progress, was not as fortunate in the new system. Pine’s grade plummeted to a “D,” and the school was named a focus school. Another Michigan City elementary school, Edgewood, fared even worse. After earning a string of average grades previously (like Knapp), Edgewood received an “F” and became a priority school, when it had not been in improvement under NCLB the year before.

At a glance, student performance at the three schools does not provide many clues as to why Edgewood and Pine are called out for interventions under waivers but not NCLB, while the reverse is true for Knapp. All perform below state averages. And all three had seen both progress and declines in student proficiency rates over time.

But proficiency rates are not the only way, or perhaps even the best way, to judge school performance. So Indiana looked to other measures to determine each school’s rating. The state added performance-based student subgroups and individual student growth measures to the mix. These changes made the difference for Knapp, Edgewood, and Pine. Based on proficiency rates alone, each school earned a “D” and would have been a focus school.

Of course, Indiana is in the process of rewriting the formula used to calculate A-F school letter grades so students are compared to their past performance, not to their peers.

“I think any time you tinker with your methodology — and in Indiana’s case, any time you tweak your A-F grading system — it could certainly have implications for which schools are priority and which schools are focus,” says Hyslop.

Indiana schools will be rated one more time using the old system. Scores for the 2012-13 school year are expected to be released Friday at the State Board of Education meeting.