What do LCD Soundsystem, Johannes Suzoy, the Beastie Boys, and Antoine Busnoys all have in common?

Give up?

They've all engaged in the art of musical name-dropping, paying respect to the masters that came before them. This week on Harmonia, we'll bring you music that gives credit where credit is due. Plus, our featured release by Musica Nova showcases a work that was written in memory of Guillaume de Machaut.

Let's begin with a late fourteenth-century motet composed by Bernard de Cluny, containing three separate texts. Two manuscripts are known to contain copies of this motet. Whoever wrote the poetic verses acknowledges musical masters both living and deceased, in addition to calling attention to Bernard himself as one who "sustains the practice of art with theory, offering his work to all as a gift of Salvation."

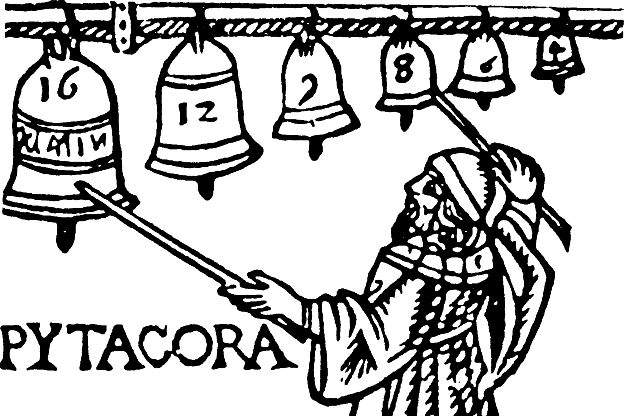

One of the texts mentions Pythagoras and Boethius, two gentlemen who some consider the founding fathers of music theory. Pythagoras receives several shout-outs from composers elsewhere in the Middle Ages and Renaissance as well.

[At the end of this motet, the third texted line notes the members of a "collegium of musicians" numbering twelve. Among this collegium are names well-known today, like poet-composer Guillaume de Machaut, composer and singer Egidio da Morino, and composer-theorist Philippe de Vitry.]

Pythagoras and the Old School

In medieval teaching treatises, it was often mentioned that part of attaining mastery was copying a master or expanding upon something that a master had already created. Homage in early music, however, was often paid in far more complicated ways.

One of the most popular methods of acknowledging one's gratitude was to mention the master's name in a musical work.

An early example of this shows up in a ballade tribute by Johannes Suzoy, a composer represented by only three works, which are found in the late fourteenth-century manuscript the Chantilly Codex.

Greek philosopher Pythagoras-known for his contributions not only to acoustics and music theory but also to mathematics and a host of other intellectual arenas-is the first to appear in Suzoy's ballade.

The second is Jubal, a biblical figure who is said to have been the father of all who play the harp and flute. (He's the son of Lamech, who is mentioned in a different work from the Chantilly Codex.)

Finally, Orpheus-that revered musician from Greek mythology who's able to sway all living creatures with his voice and lyre-is given a mention.

The text refers to these fellows as "the first fathers of melody," with the declaration that "all who live today should praise their skill and mastery and rightly show that music is the source of all honor and of the highest love."

Up on the pedestal with Busnoys and Ockeghem

A teacher doesn't have to be moldering in the dust in order to have tribute paid; living mentors are also frequent subjects of praise.

One entertaining case of friendly compliments and challenges emerged from a pair of Franco-Flemish composers who both worked around 1465 at the collegiate church of St. Martin in Tours.

Antoine Busnoys was a subdeacon and at least twenty years younger than Johannes Ockeghem who was the treasurer, yet both rose to positions of prominence in the musical elite of the Low Countries.

Busnoys must have thought very highly of the old master, as evidenced by a motet he wrote a couple of years later at the court of Charles, Duke of Burgundy.

The lengths to which Busnoys goes to sing praise of Ockeghem are truly magnificent. In the text, he compares his mentor with Pythagoras's "discovery" of the proportional qualities of musical intervals, and ends the motet by saluting Ockeghem as the "true image of Orpheus."

The technical accomplishments hidden in this motet are remarkable. Busnoys used Pythagorean intervals to organize and shift around the lowest vocal line's notes, and that changed the speed at which they are sung. So when Ockeghem's name finally shows up in the text, it's accompanied by a pattern of notes that becomes a sort of "theme" for the motet until its closure.

What is fascinating about this musical tribute is that Ockeghem apparently returned the compliment by composing an even more technically subtle motet called "Ut heremita solus" for Busnoys. The title makes a pun out of the word "hermit," in reference to Busnoys's patron saint and to the fact that an intelligent hermit is alone in his impressive accomplishments.

Ockeghem also took the "theme" that was joined to his name in "In hydraulis" and modified it into a completely different set of transformations for his motet in response to Busnoys, effectively tipping his hat to his protege.

Lamenting our master and good father

Sometimes we lose our chance to tell a mentor what he's meant to us.

In the case of Johannes Ockeghem, his passing in 1497 was immortalized by several artists in both poetry and music. An especially touching tribute was a chanson written by Josquin des Prez as an eloquent and emotional déploration.

The text is from a poem called "Nymphes des bois" by Jean Molinet, which was also written in response to Ockeghem's death.

Josquin composed the first part of the chanson in a style like Ockeghem himself, but when the second part begins there's a shift in character to a more sparse, solemn, and introverted texture. This is where Molinet's poetry invokes the names of composers in the generations after Ockeghem who are encouraged to "put on the clothes of mourning" and "weep great tears from your eyes."

Josquin, Pierre de la Rue, Antoine Brumel, and Loyset Compère are all mentioned, offering an implicit "who's who" of Franco-Flemish composers around the beginning of the sixteenth century.

In Memoriam Guillaume de Machaut

The ensemble Musica Nova recorded a commemorative album honoring one of the fourteenth century's greatest artistic minds. Released in 2011, it is entitled In Memoriam Guillaume de Machaut, and the work that most embodies this release is the double ballade by Franciscus Andrieu called "Armes, amours."

Andrieu musically set a poem of the same name that was written by the French poet Eustache Deschamps. While the text has been adapted slightly for use by Andrieu, the gist is very much the same: that artists of every stripe should deplore the death of such a towering figure of the arts, and that all instruments should perform praises and lamentations toward his remembrance.

In a turn not unlike Josquin's imitation of Ockeghem's compositional style, Andrieu deploys a similar four-voice treatment of the ballade as Machaut once did. Machaut's tricky harmonies are even brought to the fore by Andrieu as an homage. Listen carefully to hear the dolorous exhortation of "La mort Machaut, le noble rhethouryque," or "the death of Machaut, the noble rhetorician."

Break and theme music

News hole music bed, In Memoriam Guillaume de Machaut, Musica Nova/Lucien Kandel, Anonymous, Tr. 2: Adesto (excerpt of 3:10)

:30, Orlando Gibbons: Consorts for Viols, Phantasm, Linn 2014, Tr. 2 Fantasia VI, MB 36 (excerpt of 3:41)

:60, Orlando Gibbons: Consorts for Viols, Phantasm, Linn 2014, Tr. 10 "Lord Salisbury" Pavan (excerpt of 6:18)

:30, Orlando Gibbons: Consorts for Viols, Phantasm, Linn 2014, Tr. 21 Go From My Window, MB 40 (excerpt of 4:29)

Theme:Â Danse Royale, Ensemble Alcatraz, Elektra Nonesuch 79240-2 1992 B000005J0B, T.12: La Prime Estampie Royal

The writer and producer for this edition of Harmonia is Benjamin Robinette.

Learn more about recent early music CDs on the Harmonia Early Music Podcast. You can subscribe on iTunes or at harmonia early music dot org.