Laughter and tears: two of the most human forms of expression. We laugh when we're happy-and sometimes even when we're not; and we cry for almost as many reasons as there are tears-for pride, grief, annoyance, and of course, love. But how do you to snicker-or sob-in song? This hour on Harmonia, you'll laugh, you'll cry . . . and you'll sample a featured release by John Holloway.

Here's the "Lachrimae Amantis" from John Dowland's tearful collection Lachrimae, or Seaven Teares, in a performance led by John Holloway. We'll hear more from this recording later in the hour.

Dowland had great difficulty securing a place in Queen Elizabeth's court, a situation that pained him. We don't know how many tears he shed over the fact, but he bemoaned in writing, the "strange entertainment" he received in England. He preferred [quote] "Kingly entertainment in a forraine climate," but nonetheless longed to go home.

Tracks of my tears

If you've ever experienced heartbreak, you understand the symbiosis between music and tears. Music cries with us-and sometimes for us.  And there's a long history of music for, and about, crying it out.

In the twentieth century, Smokey Robinson, Aretha Franklin and Linda Rondstadt all recorded versions of the song "The Tracks of my Tears."Â And in the seventeenth century, poet and clergyman Phineas Fletcher mined one of the more tearful sections of the bible, a passage from Luke in which a "sinful woman" lacking any water begins to wash Jesus' feet with her tears:

"Drop drop, slow tears/and bathe thy beauteous feet," Fletcher wrote.

His poem inspired several composers, but the setting that stuck and became a beloved hymn tune was a version by Orlando Gibbons.

We'll hear Song 46, as it is called, sung by the Choir of King's College Cambridge. And because it's hard to resist King's College, we'll also hear that choir sing one more appropriately tearful piece, Orlande de Lassus's "Tristis est anima mea," or "Sorrowful is my soul."

Not all tears end in more tears. Some tears eventually beget joy, as we'll see in the German baroque composer Heinrich Schutz's motet "Die mit Tränen säen": "They who sow with tears will reap with joy." The text is from the 126th psalm and is a celebration of return from exile.

As we've seen, the Bible offers plenty of scope for weeping. But for the tears to really start falling, nothing beats love. The English composer John Wilbye took on the topic in his tear-stuffed madrigal, "Weep, weep mine eyes."

Here's the not-so-cheerful text:

Weep, O mine eyes and cease not,

Out alas, these your spring tides methinks increase not.

O when begin you

to swell so high that I may drown me in you?

Flow my tears

Perhaps no composer has been so extravagant with musical tears as the English lutenist and composer John Dowland. Dowland has some reason to cry-he spent many frustrating years trying to win a post at the English court. Even so, the volume of his musical weeping is startling!

It began with a lute song: "Flow my tears," from Dowland's second book of songs. In it, the narrator bewails his fate:

"Flow my tears; fall from your springs/exiled forever let me mourn."

Dowland's tears were contagious; the "Flow my tears" tune has seen numerous reworkings over the years. Let's hear a version by Johann Schop, a lutenist, cornettist, violinist, and trombone player active at the same Danish court where Dowland spent years awaiting English preferment.

Simone Eckert plays viola da gamba in this version of Schop's "Lachrimae Pavan."

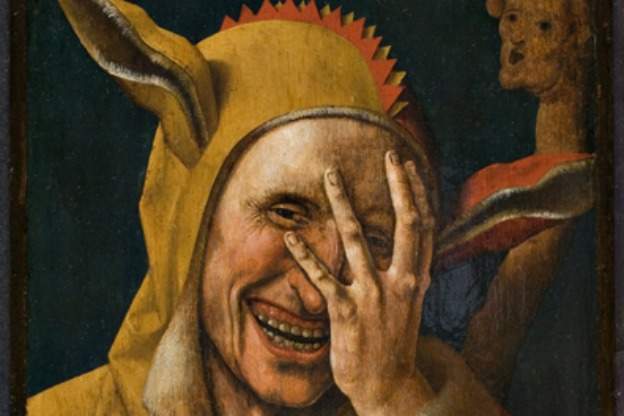

Musical giggles

Sometimes, once you've cried your eyes out, you just have to laugh. We'll turn from tears to merriment here on Harmonia, starting with the maniacal.

Evil glee is not solely the province of Disney villains. As far back as the 1600s, composers were capturing their darker characters at play. Henry Purcell's seminal opera Dido and Aeneas contains an abundant supply of laughter as the witches-evil handmaidens of a maleficient sorceress-plot the ruination of the title characters.

Let's listen to the witches plotting, and laughing, followed by a frenetic witches' dance!

We heard malevolent merriment from Henry Purcell's Dido and Aeneas, in a version from Philharmonia Baroque conducted by Nicholas McGegan.

It was a common tendency of composers of madrigals to musically "paint" words from their text. So much so, that it's sometimes called a "madrigalism."

Laughter, in particular, received special treatment, with rapid runs of notes. Let's listen for those musical giggles, heard here on the word "ridendo" (laughing), in a madrigal by the Italian composer Luca Marenzio.

Onomotopoeic joy abounds in the French composer Clément Janequin's chanson "Le chant des oysealx." The birds of the title quite literally chirp, each with its own call, enjoining listeners "to laugh and rejoice."

We'll let Claudio Monteverdi have the last laugh.

The Italian composer and opera pioneer penned Il ritorno d'Ulisse (or The Return of Ulysses) during the last years of his life. And, according to the musicologist Frederick Neumann, Monteverdi used ornaments to laugh it up-in the opera, "the trillo, specifically so labeled, is used to portray the percussiveness of stylized laughter."

We'll hear the aria "Oh dolor, Oh martir." In it, the comic character of Iro, dubbed "a parasite," bewails the loss of his income stream and comes to the not particularly laughable decision to kill himself.

Segment D: 52:30 – 57:20 (4:50)

We return to John Dowland for our featured release: Pavans and Fantasies from the Age of Dowland, a 2014 recording led by violinist John Holloway.

Dowland's series of instrumental lachrimaes, Seaven Teares figured in seaven passionate pavans, are based on his own famous song "Flow my Teares." Each of the pavans captures a different flavor of melancholy.

Let's hear Holloway's consort of violins perform one of those seven passionate pavans, the "Lachrimae Verae" or "True Lachrimae."

Break and Theme music

:30, Goe Nightly Cares, Fretwork, EMI 1990, Dowland: Tr. 3 The Earle of Essex Galiard (excerpt of 1:30)

Music under voice track, Segment b: Goe Nightly Cares: Dowland and Byrd, Fretwork, EMI 1999, B00000J2PT, John Dowland: Tr. 17. Pavan Lachrimae Verae from Lachrimae, or Seaven Teares (excerpt of 4:42)

:60, Folie Douce, Ensemble Doulce Memoire, Dorian 1998, Suite, from Michael Praetorius, Terpsichore (1612), Tr. 25 Volte CCXXII (excerpt of 1:38)

:30, Pavans and Fantasies from the Age of Dowland, John Holloway, ECM Records 2014, Tr 4 2 Airs for 4 (William Lawes) (excerpt of 3:23)

Theme:Â Danse Royale, Ensemble Alcatraz, Elektra Nonesuch 79240-2 1992 B000005J0B, T.12: La Prime Estampie Royal

The writers for this edition of Harmonia are Anne Timberlake and Janelle Davis.

Learn more about recent early music CDs on the Harmonia Early Music Podcast. You can subscribe on iTunes or at harmonia early music dot org.