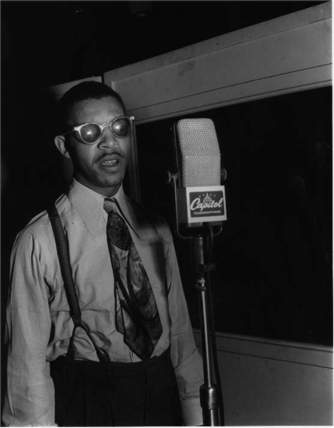

This week's program features vocalist Al Hibbler both with Duke Ellington's legendary 1940s big band, and on some rarely-heard small-group dates made with Ellington sidemen in the latter years of the decade.

Singer Al Hibbler was born in Mississippi in 1915, blind at birth, and grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas, where he studied voice at the Conservatory for the Blind. He began to work with local bands as a teenager, singing the blues at juke joints and bars around Texas and Arkansas, touring with territory bands, and eventually got an audition with Duke Ellington-but, as Hibbler later told the story, he turned up drunk and Ellington passed on hiring him, saying, "I can handle a blind man, but not a blind drunk."

Still, Hibbler kept at it and got his break in the early 1940s with Jay McShann's band, then began to sit in with Duke Ellington's band in 1943 during the band's long stay at New York City's Hurricane nightclub. The audiences responded well to Hibbler, and eventually he told Ellington he couldn't keep sitting in for free-to which Ellington replied, "Go get your money, you've been in the band for two weeks."

"Tonal Pantomime"

Hibbler became a valuable fixture in the 1940s Ellington band, spotlighted on blues and ballads, and while critics would generally have a lifelong ambivalence about his emphatic and weighty manner of singing-"You could drive a truck through that vibrato," one musician said--he did well in the jazz press polls of the time. Decades later Ellington would praise Hibbler in his memoir Music Is My Mistress, writing that "Hib's great dramatic devices and the variety of his tonal changes give him almost unlimited range…he can produce a whispering, confidential sound, or an outburst that borders on panic. He will adopt a nasal tone at just the right word and note, or affect a sudden drop to what sounds like the below-compass bass. Cries, laughs, and highly animated calls-he uses them all to make the listener see it as he sees it." Ellington called Hibbler's style "tonal pantomime," and it served the singer well on numbers both haunting and earthy, such as "Strange Feeling" and "I'm Just a Lucky So-and-So."

Another Kind of Stage Fright

Duke Ellington was protective of his blind singer, and the two formed a special working relationship. "He'd guide me out to the mike from the wings by talking," Hibbler said. "I'd walk straight to his voice. I'm the straightest walker you'd ever see, and I never used a cane. When it was time for me to come off, Duke would talk from the wings, and I'd follow his voice again. When we walked in the street, he'd put his shoulder to mine every so often, and I'd follow again. That way a lot of people never knew that I was blind." Ellington benefitted from their special relationship in his own way, later commenting that "I learned a lot from Hibbler, I learned about senses neither he nor I ever thought we had."

Still, Hibbler occasionally ran into problems. There are lots of legendary stories about fights breaking out at big-band shows in the 1930s and 40s, and Duke Ellington told one to the jazz press in 1947, about a recent concert he'd played in Palatka, Florida. Supposedly the band was playing and Hibbler was singing "Don't Take Your Love From Me" when they heard what sounded like a couple of gunshots. The band kept playing and Hibbler kept singing, until they heard more gunshots, at which point the musicians abandoned the stage. In the safety of the dressing room, above the noise of the chaos on the dance floor, they heard Hibbler still singing. Nobody had remembered to guide him offstage. The press report concluded:

One dancer was killed, another paralyzed for life, all over a woman… and to the strains of "Don't Take Your Love From Me.'

Singing With the Duke's Men

In addition to his studio sides with Duke Ellington's orchestra, Hibbler made several dates under his own name in these years with fellow members of the Ellington band. Hibbler had a great deal of respect for them; years later, possibly referring to either Ben Webster or Al Sears, he said, ""Duke's tenor player taught me a lot about singing. I would sit beside him and he'd take that horn and blow low notes right in my ear. 'Get down there, way down,' he'd say."

Quincy Jones, a young big-band fan in these years, noted the affinity between Hibbler and another Ellingtonian-baritone saxophonist Harry Carney. "I liked Hibbler with Duke," Jones said. "He had the same sound as Harry Carney's baritone sax in the band that coarseness, the deep-rooted earthiness and warmth."

Al Hibbler would continue, off and on, with the Ellington orchestra until 1951, and he'd go on to establish a successful solo career recording for Decca in the mid-to-late 1950s. I'll feature that later period of Hibbler on a future Afterglow. Here's the New York Times' writeup on Hibbler after he passed away in 2001.